Government “Tsars” need to be accountable, too

The use of Government “Tsars” – experts brought in to advise Ministers on particular policy areas – has exploded in recent years, with the current Government appointing over 100 since coming to office in May 2010. Here, Ruth Levitt and William Solesbury show that the role of these “Tsars” is ill-defined and poorly recorded, and conclude that they fail to meet the standards of proper democratic accountability.

Lord Sugar, a Business Tsar in the previous Labour Government, parked in the House of Lords (Credit: Sehar Mahmood, CC BY)

You probably know of Andew Dilnot, John Vickers and Mary Portas as government advisers or so-called ‘tsars’ – on social care, banking reform and the future of the high street respectively. What of Graham Allen, Reg Bailey, Pauline Neville Jones or Charlotte Leslie? They too were appointed to advise Coalition ministers: Allen on early years intervention, Bailey on the commercialization and sexualization of childhood, Neville Jones on cybersecurity, Leslie as a Big Society Ambassador. If they’re less well-known that’s not surprising, since the Coalition has appointed more than 100 such independent policy advisers since 2010. For over 15 years tsars have been a growing, unrecognized and largely hidden source of influence on ministers’ decisions.

Individual appointments are usually announced in a departmental press notice, yet neither departments nor the Cabinet Office maintain proper records about all of them. Departments’ Annual Reports rarely note the progress of these advisers’ work. Some tsars never even produce a written report, presumably briefing ministers and officials in other ways, if at all. Only occasionally have Select Committees picked up on the work of tsars and called them in – as did the Communities and Local Government Committee recently with Mary Portas.

In our research published last year we revealed, for the first time, the scale and scope of tsar appointments since 1997. We found that:

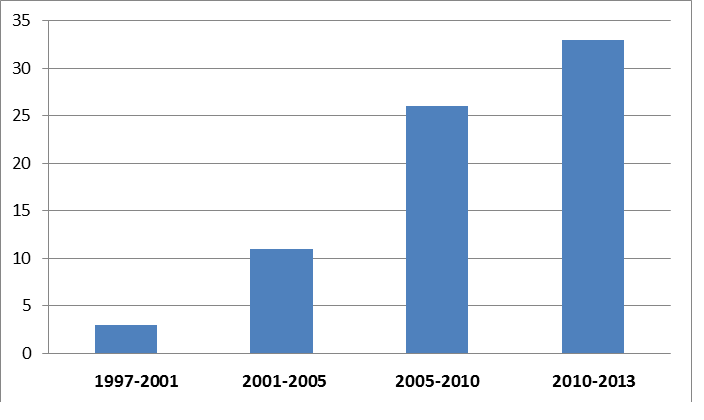

- The annual rate of appointments has increased progressively over the last four administrations (see fig 1)

Fig 1: annual rate of appointments over the last four Parliaments

- The league table of ministers who appoint tsars puts Gordon Brown in the top slot with 46 appointments in all, 23 as Chancellor and 23 as Prime Minister; David Cameron has made 21 so far.

- Tsars come principally from business (40% of the total) and the public service (37%) with a smattering of researchers, lawyers and media people; 18% were serving politicians, like Graham Allen and Charlotte Leslie above, or were formerly politicians, like Alan Milburn, the social mobility adviser.

- Some can be characterized as specialists (with relevant professional expertise in the field in which they are appointed to work); others are generalists (working outside their career expertise, applying management experience to the task) or advocates (with known expertise but also known views – the case with the politicians and certain others).

- A few come to the task with a high media profile – sometimes dubbed ‘celebrity tsars’ – ministers seem to like being associated with them.

- Overall they are strikingly un-diverse: predominantly male (85%), white (98%), over 50 years old on appointment (83%), and 38% were titled.

Interviewing tsars and their civil servant advisers showed just how ramshackle (or non-existent) the processes for their appointment and guidelines for conduct often are. There is no formal guidance and departments and appointees simply make it up as they go:

- Recruitment may be by phone call, sometimes from the minister, rarely involving a real interview – the person approached is usually known by, or known to, a minister, so it is very much a personal appointment. Pay-off to a sacked minister seems to explain some appointments.

- Background checks for possible conflicts of interest or other sources of potential embarrassment are often absent or superficial – witness the recent case of James Caan, appointed to advise on helping young people get on in work without leg-ups, only to be revealed by the media as having given employment to his own children.

- Written terms of reference are not standard practice, nor is there any requirement about how openly the tsar should conduct the work – some offer nothing more until they publish a report. It seems to be assumed that any tsar knows how to undertake serious policy analysis.

- Some of these advisers get paid, some do not (and may not wish to be), yet the subject may not even be raised at the start. Payments vary: £200K pa was the highest we identified.

- Who owns the ‘intellectual property’ and responsibility for the advice? This is rarely addressed explicitly, although it can make a big difference to the perceived independence of the work.

- Departments keep no formal records of their tsar appointments, and even struggle (and, in some cases, decline) to respond to FOI requests for information about particular appointments.

- There has been no evaluation of the performance of tsars, individually or collectively, so departments don’t really learn about good practice.

The Coalition has already appointed more tsars than special advisers (Spads). As the slimming down of the civil service continues, tsars, Spads plus advisers made into temporary civil servants could soon outnumber the senior civil servants. Perhaps that is what ministers want. In their Civil Service Reform Plan (July 2012 ) they pledged more ‘open policy making’ by greater outsourcing of policy advice, to break what they argued was Whitehall’s ‘virtual monopoly on policy development.’ That ‘monopoly’ is a myth: many sources of external advice have long been available to and used by departments and ministers – including consultants, researchers, advisory committees, scientific advisers, consultations, as well as tsars.

The government has missed the crucial point about accountability and openness. All the other sources are ‘regulated’ through codes of practice, to make proper and effective arrangements. Only tsars remain unregulated. Our research shows that there are advantages for ministers in having access to external advice on the flexible, informal and speedy basis that tsars provide. That does not have to mean hasty, careless or clandestine practices.

These are public appointments, funded by public money. They have to be accountable. Neither the Cabinet Office nor the Commissioner for Public Appointments seems willing to secure that accountability. Tsars do not even have to observe the Seven Principles of Public Life.

That is why we launched a draft code of practice for independent policy advisers on 15 October 2013 at King’s College London.

This is a short, simple code, drawing on the advice of a number of former tsars, civil servants who worked with them, journalists and academics who observe the ways of Whitehall. The code addresses propriety and effectiveness. Regarding propriety, the code sets basic, minimum steps for selection and appointment, with continuing oversight by a senior responsible official; clarity about remuneration; assessment of conflicts of interest in advance; written terms of reference; greater diversity in the appointees; and a commitment to publicize tsar appointments, to publish their reports and to respond formally to them.

For effectiveness the code requires more thought to be given to job and person specifications to help to identify candidates with relevant experience or expertise; the code encourages tsars to be open in how they conduct their work; and a final, fully evidenced and argued report should be the norm. Also that the work of tsars should be reported in departments’ Annual Reports and that departments should periodically evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of previous appointments to inform the development of good practice.

Media coverage of our code prompted the Cabinet Office to state: “It is entirely appropriate, and in the public interest, for Government to draw on a wide range of advice. Successive administrations have chosen to bring in external expertise in various ways to provide an additional resource to ministers in considering difficult and complex issues. We think it’s important to maintain a degree of flexibility in such appointments, particularly since they may be required to be made at short notice.”

Indeed – but flexibility and speedy action are not incompatible with propriety and effectiveness. Nor can they be an excuse for inadequate democratic accountability.

Note: this post represents the views of the authors and not Democratic Audit, or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1a8GIvH

|

Ruth Levitt is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow in the Dept of Political Economy at King’s College London, and an independent researcher working on public policy analysis and evaluation studies in academic and not-for-profit environments. Recent studies include policy tsars, the role of outsiders in Whitehall, the use of evidence in audit, inspection and scrutiny of UK government, and the role of evidence in the UK’s policy making on GM crops. |

|

William Solesbury Solesbury is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow in the Dept of Political Economy at King’s College London, and an independent researcher and writer. His past research has focused on the interplay of evidence and policy, including work (with Ruth Levitt) on the role of outsiders in Whitehall, the use of evidence in audit, inspection and scrutiny of UK government, and the practice of policy tsars as government advisers. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.