The political affiliations of the UK’s national newspapers have shifted, but there is again a heavy Tory predominance

The 2010 General Election saw the Conservatives gain a number of newspaper endorsements, and failed to win outright. But while there is a consensus that newspaper endorsements matter less today than they once did, they remain a significant force in shaping the political outlooks of their readers. In the 2012 Audit of Democracy, Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone looked at the representativeness of newspaper opinion related to the British public, and concluded that newspapers were becoming ever more fluid in their political outlooks.

There is rarely any significant concern expressed about the extent to which UK news broadcasting is representative of different political opinions. As we note in Section elsewhere, the BBC’s own codes and guidelines have been highly successful in maintaining its reputation for balanced reporting and for ensuring that a platform is provided for a range of political views to be heard. While there have been occasional controversies, these should not deflect attention from the widespread consensus that the BBC provides impartial and balanced coverage. A survey conducted by Ipsos MORI in 2008 found that levels of public trust in the BBC were far higher than those for the media in general and that the BBC was regarded as the most trusted of seven organisations, which included the NHS, the Church of England and the military.

We therefore concentrate here primarily on the issue of the balance of political opinion in the UK national press and its potential political implications. Given the absence of any requirements for individual newspapers to offer balanced news reporting and comment, the range of views on offer in the British press derived largely from the extent to which there is pluralism of ownership and, in turn, the degree to which owners seek to influence editorial direction. As we noted in Section 3.1.1, newspaper ownership in the UK, as elsewhere, is strongly concentrated and there have been widespread concerns expressed about the extent to which this has restricted a plurality of viewpoints.

Writing almost two decades ago, Marsh noted that ‘the press overwhelmingly supports the Conservative Party’. Likewise, Wright suggests that ‘the businessmen and corporations who own newspapers have generally felt their interests coincided with Conservative policies and their editors have reflected this view’. That most newspaper owners should seek to define the political stance taken by their publications is not especially surprising. As Marsh suggests, newspapers are rarely profitable and it is therefore difficult to avoid the conclusion that ‘the press barons are in newspapers for power, influence and easy access to the establishment’.

Likewise, the mechanisms through which owners can, and do, interfere with or shape content to promote particular viewpoints are not difficult to identify; they range from directly dictating the line a newspaper should follow on particular issues, to appointing senior staff with a shared political outlook, as well as forms of indirect influence over the ethos of the organisation which may prompt journalists to engage in ‘self-censorship’.

Yet, it would also be misleading in the extreme to assume that the UK press as a whole presents a unified, default pro-Conservative position, as dictated by their owners. The extent to which proprietors interfere with content is entirely unquantifiable, but there are also clear limitations on the extent to which they will be able to do so. The size and complexity of national newspapers and broadcasters, and the competing professional values and political views of journalists, editors and producers ensure that a media organisation represents far more than simply ‘the voice of its owner”. Just as importantly, there is also evidence to suggest that the political affiliations of the UK’s national newspapers has become significantly more fluid. With voters increasingly de-aligned from political parties, there is a powerful rationale for the press to follow suit, if only to avoid alienating their own readers.

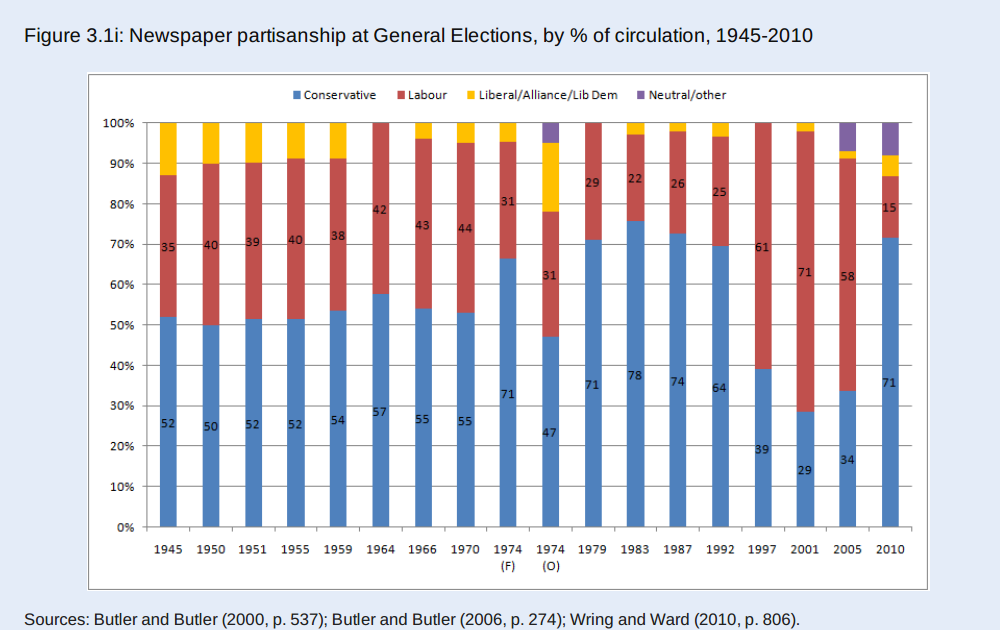

Figure 3.1i shows the partisan orientation of the UK national press, by share of circulation, at general elections from 1945 to 2010. Measured in this way, the Conservatives typically enjoyed 50-55 per cent of press support by circulation, Labour between 38 and 44 per cent and the Liberals 5 to 10 per cent. However, this relatively stable pattern of partisan support was clearly disrupted from the mid-1970s.

There was an initial shift of support towards the Conservatives, who could count on the endorsement of around three-quarters of press circulation from 1979 to 1987. However, from 1997 to 2005, the proportions were essentially reversed, owing partly, but by no means entirely, to Tony Blair’s success in persuading Rupert Murdoch to switch the allegiance of his newspapers. There has been much debate about the extent to which press bias impacts on voting behaviour.

The Sun’s infamous claim following the 1992 general election that ‘It’s the Sun Wot Won it’ is widely known. Yet, in almost half of all general elections since 1918 ‘one newspaper or another has claimed to have swung the result’. Indeed, the case for media supremacy in politics is far from proven and that ‘elections are won or lost by parties and their rival candidates for the post of prime minister, not by the media’.

There are certainly significant methodological difficulties which arise from any attempt to establish the degree of cause and effect in media reporting and voting behaviour. It has been found, for instance, that 68 per cent of Sun readers at the time of the 1979 general election were unable to correctly identify that the paper advocated voting Conservative.

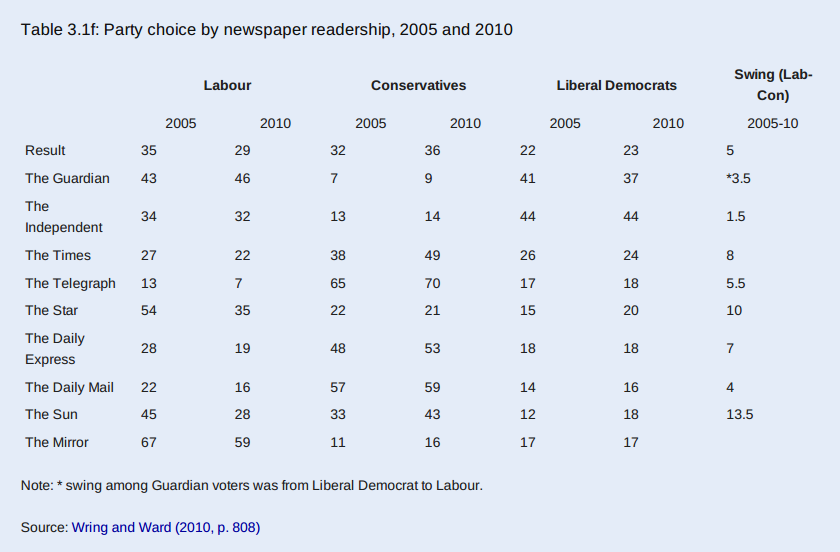

Clearly, there is a relationship between the partisan position of newspapers and voting preferences among their readers. As Table 3.1f shows, only nine per cent of Guardian readers voted Conservative in 2010, compared to 70 per cent of Telegraph readers. Similarly, the strongly Labour-supporting Mirror was the only tabloid with a majority of readers (59 per cent) voting Labour in 2010.

What is also evident from Table 3.1f is that, while the voting swing among readers of all newspapers, other than the Guardian, was broadly in line with the national result, the shift was much stronger among readers of the Sun and the Star. However, it should also be underlined that the spread of party support among readers of different newspapers is such that, in 2010, one-third of readers of the staunchly pro-Conservative Daily Mail voted either Liberal Democrat or Labour, while the same proportion of Mirror readers opted for either the Liberal Democrats or the Conservatives.

Moreover, even if we accept that there is, broadly speaking, a clear fit between the political views expressed by newspapers and those held by their readers, it is by no means clear how this relationship should be interpreted: ‘[it] might indicate either that readers’ political views are shaped by the paper that they read or that they choose to take a paper which is politically congenial to them’

—

This post is based is based on extracts from the 2012 audit of UK democracy. For further discussion and full data sources see section 3.1.2 Media diversity and accessibility. Please see our comments policy before posting. Shortlink for this post: https://buff.ly/18kQvAH

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The politics of newspapers:

“@democraticaudit: The political affiliations of the UK’s national newspapers https://t.co/YGkgHJYgS3”

The political affiliations of the UK’s national newspapers have shifted, but there’s again a heavy Tory predominance https://t.co/WHoSYd9CRH

“@democraticaudit: political affiliations of the UK’s newspapers have shifted, but a heavy Tory predominance https://t.co/U2m1XpFmbO” intrstg

political affiliations of newspapers in the UK have shifted, but are still largely right-wing https://t.co/q8qjegtpd0

The political affiliations of the UK’s national newspapers have shifted, but there is again a heavy Tory predominance https://t.co/cWX4sClGhS

The affiliations of the UK’s newspapers have shifted, there is again a heavy Tory predominance : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/QQlmIogrh9