The election of an ‘outsider’ as Labour leader is linked to new selection rules and the ideological alternative on offer

Conventional wisdom has it that rank outsiders do not become leaders of ‘mainstream’ British parties, yet Jeremy Corbyn now presides over the Labour Party. Pete Dorey and Andrew Denham reflect on the criteria which have fed into leadership selection before now and argue it was changes to the selection rules and the offer of a clear ideological alternative to recent leaders that allowed Corbyn to win such an unexpected and decisive victory.

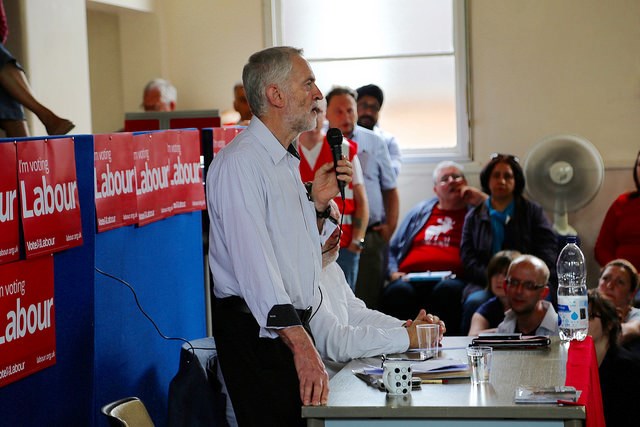

Credit: Ciaran Norris CC BY-NC 2.0

Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Leader of the Labour Party has stunned observers and practitioners of British politics. Conventional wisdom has it that rank outsiders do not become leaders of ‘mainstream’ British parties. Candidates with a long history of rebellion against their own party, no practical experience of government or party management, and supported by very few of their parliamentary colleagues, are seldom seen as ‘leadership material’.

Instead, as Leonard Stark argues in his excellent book Choosing a Leader (1996), the winning candidates in British party leadership elections have usually been those considered best-equipped to meet three criteria: unity (the ability to maintain or restore party unity); electability (the ability to win a General Election) and competence (the ability to implement successful policies, and so lead a successful administration). Of the six Labour leaders elected between 1963 and 1994, Stark argues, two (Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock) were elected mainly on the basis of the first criterion of restoring party unity. The other four (Harold Wilson, James Callaghan, John Smith and Tony Blair) were chosen on the basis of all three criteria – as was Gordon Brown, the only candidate for the succession when Blair resigned in 2007.

From 1963 to 2007, most newly-elected Labour leaders had been favourites from the outset and the campaign made little difference to the outcome. In 2010, this changed when Ed Miliband pipped his older brother, David, to the post. David Miliband remained throughout the first choice of most MPs and ordinary Party members, but Ed’s far superior support among the few union members who actually bothered to vote meant that David’s superior opinion poll ratings in respect of both electability and competence ultimately counted for nothing.

In 2014, controversy over the selection of Labour’s candidate for a by-election in Falkirk led to a review of its organisation, including the rules to select future leaders. Until this time, Labour had operated an Electoral College, comprising three sections: MPs and MEPs, members of trade unions and other organisations affiliated to the party and party members. In an attempt to dilute the influence of union leaders and officials in future leadership elections, the 2014 reform effectively abolished the Electoral College, and replaced it with three somewhat different categories: full party members; ‘affiliated supporters’ and ‘registered supporters’. ‘Affiliated supporters’ were those who belonged to a union or other organisation affiliated to Labour, but who now had to register (at no extra cost) as a supporter of the Party in order to vote. ‘Registered supporters’ were those who wished to declare their support for Labour and its values, but without becoming full members. Instead, for a fee of just £3, they could become ‘registered supporters’, and as such vote for the next leader. Crucially, this new system was based on the principle of One Member One Vote, pre-empting Conservative claims that the Labour leader owed their election to the power of union leaders.

Corbyn only secured the 36 nominations required from MPs with moments to spare, compared to the 68 who nominated Andy Burnham, 59 who endorsed Yvette Cooper and 41 who backed Liz Kendall. Yet, having started as a rank outsider – Burnham was initially tipped as the likeliest winner – Corbyn’s popularity soared among members and supporters alike. Indeed, the more the ghosts of New Labour’s past, including Blair himself, warned of the lasting damage a Corbyn victory would inflict on the Party, the more his popularity increased, as evidenced by various opinion polls, and the packed meetings he addressed across the country.

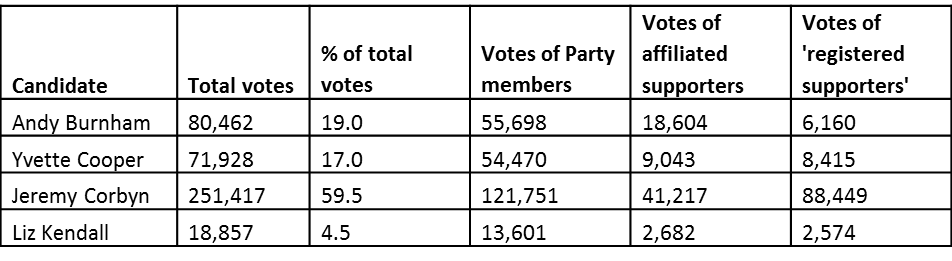

When the result was announced on 12 September, it was clear that Corbyn had won decisively, as illustrated below:

Table: 2015 Labour leadership election results

The leadership contest had used the Alternative Vote (AV) procedure, whereby if no candidate won more than 50% of the votes cast, the last-placed candidate would be eliminated, and the second-preference votes on their ballot papers redistributed to the remaining candidates, until one of them secured an overall majority. Such was Corbyn’s support, however, that he achieved a majority in the first round.

Intriguingly, Corbyn’s popularity among Labour supporters in the country is in inverse proportion to his standing with the Party’s MPs, as indicated by the small number who nominated him in the first place. Indeed, the announcement of his victory prompted the immediate resignation of several members of Labour’s front bench, and subsequent announcements by other senior figures that they were unwilling to serve in his Shadow Cabinet.

Evidently, many of those who voted for Corbyn wanted to register their opposition to the ‘politics of austerity’ and ‘reclaim’ Labour from the Blairites, whom many on the Left consider to be ‘Tory-lite’. To those who argue that the Conservative victory in the 2015 General Election proved that the British electorate supports ‘austerity’ (albeit as an unfortunate necessity), his supporters respond that this was mainly because the political arguments against austerity were not articulated with sufficient vigour or conviction by senior figures during the campaign. In short, Corbyn is viewed by his supporters as the candidate best-equipped to challenge the pro-austerity, neo-liberal, consensus which mainstream parties and politicians have hitherto endorsed.

Another factor which explains Corbyn’s popularity is that, for some on the left of British politics, ‘principled’ opposition is preferable to what they regard as the ‘betrayals’ of previous Labour governments. While many of Corbyn’s supporters hope he can lead Labour to victory in 2020 on a populist left-wing programme, others are more concerned that the party should rediscover and affirm its ‘traditional’ values, vigorously and consistently opposing Conservative policies. To those who argue that Corbyn will reduce Labour to a party of mere protest, rather than power, some of his supporters are inclined to respond that this is preferable to embracing a neo-liberal agenda, as New Labour did, for reasons of political expediency.

—

This post represents the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting

—

Pete Dorey is Professor of British Politics at Cardiff University.

Pete Dorey is Professor of British Politics at Cardiff University.

Andrew Denham is Reader in Government at University of Nottingham.

Andrew Denham is Reader in Government at University of Nottingham.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The election of an ‘outsider’ as Labour ldr is linked to new selection rules and the ideological alternative on offer https://t.co/aL8GfZYnie

The election of ‘outsider’ as @UKLabour leader is linked to new selection rules & ideological alternative on offer https://t.co/sM3bZVEH2q

The election of an ‘outsider’ as Labour leader stems from new selection rules & the ideological alternative on offer https://t.co/2CCRl8wU1H

The election of an ‘outsider’ as Labour leader is linked to new selection rules and the ideological alternative on… https://t.co/ZElqRPmgbL

Interesting insight on @democraticaudit as to how a rank outsider was elected to lead @UKLabour: https://t.co/eJbI3YSnX5

The election of an ‘outsider’ as Labour leader is linked to new selection rules and the… https://t.co/TovQKlX1Zj https://t.co/u2xSOqbIZW