The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong

Have you ever voted for another party because you felt that your party had no chance of winning the seat? If yes, then you might be among the 5 to 10 per cent of tactical voters. In this article, Michael Herrmann, Simon Munzert, and Peter Selb explain how, contrary to popular belief, the Liberal Democrats were the big winners of tactical voting in 1997 and 2001.

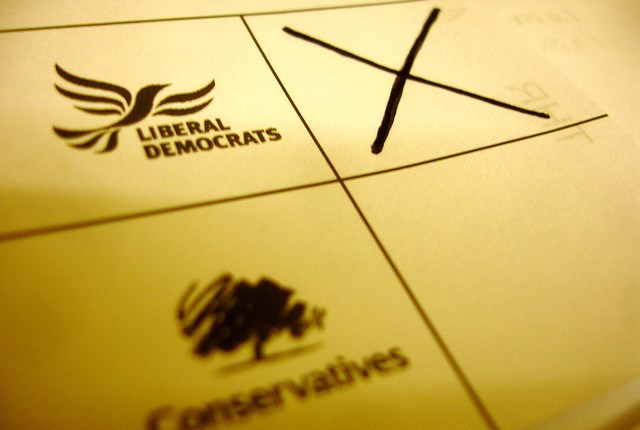

Tactical voting aims at influencing the outcome of an election. Some argue that it’s unethical to vote tactically because you don’t vote for the party you really prefer. Yet, the system of first past the post doesn’t exactly reward loyalty if loyalty means voting for a party that stands no chance of winning. In these situations, voters might be forgiven for trying to make their ballot count by voting tactically.

The common belief is that tactical voting hurts the Liberal Democrats

There is a good deal of evidence to suggest that tactical voting exists. Research shows that most tactical votes go away from the Liberal Democrats and towards either Labour or the Conservatives. So, conventional wisdom is that tactical voting hurts the Liberal Democrats and helps the Conservatives or Labour.

To our surprise, we found that such conventional wisdom can be very wrong. In fact, tactical voting won the Liberal Democrats more seats than it did for Labour or the Conservatives in past elections.

By looking at the 1997 and 2001 general elections, we tried to determine the effect that tactical voting had on the number of seats won by each party. We considered all 528 constituencies in England. In line with common wisdom, we found that most tactical votes went away from the Liberal Democrats and towards the other two parties. However, when we looked at constituencies where tactical voting may have flipped the outcome, the Liberal Democrats turned out to be the clear winner.

Tactical voting won the Liberal Democrats more seats than other parties

Here are the numbers: for the Labour landslide election of 1997, our results suggest that the Liberal Democrats won 21 seats due to tactical votes by Labour supporters. By contrast, Labour only won 9 seats due to tactical votes by Liberal Democrat supporters. Based on a different calculation, in which we assumed that voters in 1997 anticipated that Labour would perform considerably better than in previous elections, our results suggest that the Liberal Democrats won 17 seats due to tactical votes and Labour 11. In both scenarios, tactical voting by Labour supporters won the Liberal Democrats more seats than tactical voting by Liberal Democrat supporters did for Labour.

The numbers get more drastic when we consider that the Liberal Democrats won a total of 34 seats in England in 1997. Thus, tactical voting probably accounted for something between half and two-thirds of the seats that the Liberal Democrats won in England in that election.

For 2001, which had a very similar similar outcome to that of 1997, our results suggest that tactical voting won the Liberal Democrats 12 seats and Labour only 3.

Success due to geography and different tendencies of voters to vote tactically

Why did tactical voting benefit the Liberal Democrats? Initially, the result seems paradoxical because our calculations also indicate that most tactical votes were not for the Liberal Democrats. A closer look at the results, however, revealed two explanations: one has to do with geography; the other has to do with voters’ tendencies to vote tactically.

Geographically, the Liberal Democrats were stronger in some parts of England, like the South and South West, than in others. This means that there were constituencies where the Liberal Democrats had better chances of winning than Labour. In those constituencies, the Liberal Democrats profited from tactical votes by Labour supporters who tried to avoid a Tory victory.

Our results also show that the tendency of Labour supporters to switch to Liberal Democrat was stronger than Liberal Democrat supporters’ tendency to switch to Labour. This meant that in seats where Labour came third, Labour supporters were almost twice as likely to vote tactically than Liberal Democrat supporters in seats where the Liberal Democrats came third.

Taken together, the Liberal Democrats lost more votes than the other parties because they came third in most constituencies; however, those votes didn’t translate into sizeable seat gains for Labour because the number of Liberal Democrat supporters who switched to Labour in each of those constituencies wasn’t large. By contrast, a large number of Labour supporters switched to the Liberal Democrats in those constituencies where the Liberal Democrats stood a chance of winning. And this helped the Liberal Democrats to secure those seats.

Lastly, we also found tactical voting with regard to the Conservatives. In the few constituencies where the Conservatives came third in 1997 or 2001, our results suggest that Conservative supporters were about as likely to switch to Liberal Democrat as Labour supporters were in seats where Labour came third. Again, this helped the Liberal Democrats to win those seats. The Conservatives also gained tactical votes from Liberal Democrat supporters, but only in 2001. Overall, the Conservatives did not benefit from tactical voting.

A new, more solid approach to inferring tactical voting

The possibility that tactical voting may have helped the Liberal Democrats in the past has not escaped scholars. Yet in our study, we applied Bayesian image reconstruction techniques to data sets containing survey responses from thousands of voters. We were thus able to compare voter preferences in each constituency to the actual voting returns. This puts our inferences on a much more solid footing than previous studies.

Our study looked at the 1997 and 2001 elections so we can’t really say whether the Liberal Democrats benefited from tactical voting at later elections. This would seem less likely for the most recent election, given the Liberal Democrats’ weak electoral performance. But in 2010, for example, things could have been different. What our results show is that simple rules of thumb about who wins or loses from tactical voting can be very misleading.

___

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit, nor of the London School of Economics. It originally appeared on the LSE Politics and Policy blog. Please read our comments policy before posting.

___

Michael Herrmann is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Michael Herrmann is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Simon Munzert is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Simon Munzert is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Peter Selb is Professor for Survey Research at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Peter Selb is Professor for Survey Research at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong https://t.co/VGUM6yoXZw

Another factor may be how voters view parties that they do not support

Labour and the Conservatives tend to be detested whilst the Liberals tend to be pitied – certainly they are seen as less of a threat.

Labour and Conservative supporters may therefore be more likely to vote for a pitied party to keep out a detested one. Liberal supporters however are less likely to vote for a detested party just to keep out the other detested party.

That the Liberals gain under tactical voting would then seem unsurprising.

Contrary to popular belief, the Liberal Democrats were the big winners of tactical voting in 1997 & 2001 https://t.co/bA4fJKlhYj

I am surprised that the common belief is that the LibDem’s were hurt by tactical voting. I have always thought that they benefited from it. I live in a constituency (Cheadle) that has very favourable demographics for the Tories. And yet in 2001, the LibDem’s narrowly gained the seat, clearly due to tactical voting from Labour voters – the Labour vote is consistency low (around 15%). But then in seats where the LibDems came third, they had little chance anyway so tactical voting is hardly hurting them. I’d actually argue that very seats in the UK have a pularity of people who support the LibDem’s (which is painful as I am a LibDem member). Maybe only Orkney/Shetland was the exception. Even in Westmorland and Lonsdale, I think the strong LibDem vote if for Farron, and also from Labour voters, and not for the party.

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong, write Michael Herrmann, Simon Munzert & Peter Selb https://t.co/M5s3QVNTjQ

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong https://t.co/JkRCPoA1iV

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/YiCZXh87x7

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong https://t.co/9F2MLp2guv in @democraticaudit, or full article https://t.co/iBI8ULD76R

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong https://t.co/fdMsH56HJ0

The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong https://t.co/M89MVtkb5w https://t.co/EYsMn9HG7o

@democraticaudit #nomoretacticalvoting for me!