Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK

Recent years have seen an increase in membership of some of the smaller parties but this has not compensated for the overall decline in party membership across the UK. Andrew Defty considers the implications of this, from the reduced revenues to the key role played by party activists.

There has been a long term decline in membership of the mainstream political parties in the UK. In the mid 1950s membership of the Conservative Party stood at around 3 million while the Labour Party had around 1 million members. By the time of the 2015 general election, the Conservative Party had a membership of around 150,000 while Labour Party membership stood at about 270,000. Recent years have seen an increase in membership of some of the smaller parties, most notably UKIP, the SNP and the Green Party, but this has not compensated for the overall decline in party membership across the UK. Only around 1% of the UK population is now a member of a political party. Although party membership has been in decline across Western Europe, the UK now has the lowest level of party membership in Europe.

Declining revenue

The most obvious consequence of declining membership is that parties have faced a decline in revenue from membership fees. This does not, however, affect all parties equally. Parties have never been entirely dependent on individual subscriptions and have always sought to generate other sources of income. These include individual and corporate donations, affiliation fees such as the Labour Party receives from the trades unions, and commercial investments. The extent to which parties have been successful in generating alternative sources of revenue affects the degree to which they have been able to cushion themselves from declining membership.

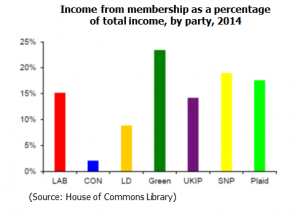

The graph opposite, from the latest excellent House of Commons library note on party membership, shows the proportion of party income which comes from membership revenue. This shows that the bulk of income for all parties comes from sources other than subscriptions, and also that there is a wide variation in the extent to which parties are dependent on membership. While 23% of Green Party income comes from membership fees, this comprises only 2% of Conservative Party income.

The graph opposite, from the latest excellent House of Commons library note on party membership, shows the proportion of party income which comes from membership revenue. This shows that the bulk of income for all parties comes from sources other than subscriptions, and also that there is a wide variation in the extent to which parties are dependent on membership. While 23% of Green Party income comes from membership fees, this comprises only 2% of Conservative Party income.

Alternative sources of income

While the development of alternative sources of income has allowed the parties to offset the decline in subscriptions, the growing dependence on donations raises questions about the political system being captured by powerful interests. Critics of the Labour Party have long complained that the party is in thrall to the trades unions. The obvious response to this is that these are mass membership organisations which represent millions of working people across the UK. However, trade union membership has also been in steep decline since the 1980s and it is, of course, far from clear that all trade union members also support the Labour Party.

Attention has also focused on the extent to which parties have become dependent on donations from a small number of wealthy individuals. According to a recent report, since David Cameron became leader, twenty-five individuals have donated more to the Conservative Party than the party’s total annual income from membership subscriptions. Given the extensive powers of patronage available to the Prime Minister, with seats in the House of Lords and a range of other honours in his gift, dependence on wealthy donors can lead to obvious accusations of honours being traded for cash. Dependence on wealthy donors can also prompt questions about whether such individuals have an influence on policy. Questions were raised about Labour’s relationship with wealthy donors in 1997 when, following an announcement that a ban on cigarette advertising would include an exemption for Formula 1 racing, it was revealed that the formula 1 chief executive, Bernie Ecclestone, had earlier donated £1 million to the Labour Party.

If one donor can provide more financial support than the entire party membership, why do political parties bother with the difficult, and often fruitless, task of trying to persuade large numbers of people to join? The simple answer is that parties, or at least parties which hope to win elections, don’t just need money, they also need people. While political parties have become increasingly sophisticated organisations with a cadre of professional policy wonks, media managers and spin doctors, when it comes to fighting elections they remain heavily dependent on a large number of volunteers to knock on doors, deliver leaflets and make phone calls.

Even in the United States, where presidential candidates must raise a war chest amounting to many millions of dollars before they can even consider running for the presidency, campaigns are still dependent on an army of activists. The bulk of campaign finances will be spent on advertising, facilities such as campaign headquarters, banks of computers and telephones and not a little on overpaid campaign strategists, but much of the actual campaigning will be carried out by unpaid volunteers.

While British political parties may be able to generate alternative sources of revenue, it is the shrinking of the activist base which is the most worrying aspect of declining membership for most parties. Moreover, while the graph above suggests that the Conservative Party are best equipped to manage a decline in revenue from subscriptions, they are perhaps much less able to sustain the decline in members. The decline in membership of the Conservative Party has been steeper than for other parties, albeit from a higher starting point. Conservative Party members are also older, perhaps much older, than members of other parties. Establishing the age profile of party members is difficult but a reliable estimate puts the average age of Conservative Party members at 59, with over 60% of members over the age of 60. The average age of Labour Party members is generally thought to be around 52 although a recent estimate suggested that the influx of new members since the general election has seen that fall to 42. Clearly, 60 is not old and most over-60s are likely to be healthy and active. However, a diminishing and ageing activist base is not good for the health of a political party, or indeed, for the health of democracy.

—

This post originally appeared on Who Runs Britain? and is reposted with permission. It represents the views of the author only, and not those of Democratic Audit UK, the LSE Public Policy Group, or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

![]() Dr Andrew Defty is Reader at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln. He runs the Watching the Watchers blog at Lincoln University. His book, written with Hugh Bochel and Jane Kirkpatrick, on parliament and the intelligence services is also entitled “Watching the Watchers”.

Dr Andrew Defty is Reader at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln. He runs the Watching the Watchers blog at Lincoln University. His book, written with Hugh Bochel and Jane Kirkpatrick, on parliament and the intelligence services is also entitled “Watching the Watchers”.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/0H5a8O5FyT

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/iR3LvRV8iZ

@democraticaudit But @UKLabour full membership is now at 1997 levels, heading higher, with many extra affiliated members & reg. supporters

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/FaOBy3d8QJ

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/XnQKanUFQS

.@adefty writes in @democraticaudit about negative implications of diminishing and ageing political party activists: https://t.co/sAUCl3yxoU

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/oE1qswxn0H

Fewer and older: Consequences of the decline in party membership in the UK https://t.co/L9dtKjt2VG https://t.co/vvXbfUmR9V