Research from Sweden and the Netherlands shows that ‘bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures

Proponents of electoral reform in the UK often point to the more consensual nature of democracy in continental European countries as a justification for their position, but this isn’t always the case. For example, as Tom Louwerse, Simon Otjes, David M. Willumsen and Patrik Öhberg show, Sweden’s parliamentarians are notable for their adversarial behaviour when compared to the MPs of the Netherlands. They argue that adversarial ‘bloc’ politics is more likely to lead to adversarial behaviour.

Credit: Olof Sensestam, CC BY 2.0

Comparative work on the interaction between parliamentary parties is quite limited. . We do not know a great deal about the reasons why some parliaments are more consensual than others. Understanding why voting patterns differ between countries is worthwhile because it allows us to understand how political systems shape the behaviour of politicians. In our recent study in Party Politics, we examine the extent to which government and oppositions parties cooperate on legislation in Sweden and the Netherlands. We aim to explain why in the Dutch parliament government and opposition parties vote together more often than they do in Sweden.

Comparing the Netherlands and Sweden

The rationale of our study is that Sweden and the Netherlands are very similar in a lot of ways: both have multiparty systems, are parliamentary democracies and have a long history of democracy. There are some differences between the two countries that point to Sweden as being the likely case for more consensual parliamentary behaviour: Sweden has a long tradition of minority governments that need to reach across the aisle for support. The Netherlands has only recently been dabbling with minority government. Sweden’s party system has been less polarized, on average, compared to the Netherlands during our research period (2002-2014): The Dutch parliament has had radical right-wing populist party members since 2002, while the Sweden Democrats only entered parliament in 2010. Finally, Sweden is slightly more corporatist than the Netherlands, where the government and social partners negotiate policy compromises in the extra-parliamentary arena..

Whole-sale and Partial Alternation

A crucial difference between Sweden and the Netherlands is in how cabinets are formed, which in our view is central to explaining differing patterns of government-opposition cooperation in parliament. Sweden is characterised by bloc politics. There are two blocs of parties: the centre-right group, consisting of the Moderates, Centre Party, the Liberals and the Christian Democrats, and the left-wing bloc of Social Democrats, Socialists and Greens. After the election, the largest bloc will form the government (the centre-right parties) or where the Social Democrats are in government and have to rely on the support from the Greens and the Left Party.

This means that either the government can stay the same (if the governing bloc won the elections) or it can change entirely (if they lost): wholesale alternation.

In the Netherlands, government formation is far less predictable. There are three large traditional government parties: The Social-democrats, the Liberals and the Christian-democrats. After elections at least one of the three large parties stays in government, while a second rotates out and third rotates in. This pattern is called partial alternation. Sometimes smaller parties join the coalition. This means that in Sweden governing coalitions will either be clearly left-wing or clearly right-wing, while in the Netherlands cabinets can be centre-left (Christian-democrats and Social-democrats), centre-right (Liberals and Christian-democrats) or even ‘purple’ (Social-democrats and Liberals).

Since Swedish cabinets are formed, or supported, by ideologically close parties, they are expected either to govern together or be in opposition together. As a consequence, politics in Sweden is more adversarial. In contrast, in the Netherlands cabinets are formed by some parties that previously were in government and some parties that were previously in opposition, adversarial politics is much more dangerous: one of the parties that currently forming the opposition may become a coalition partner for one of the governing parties in the future.

Adversarial politics

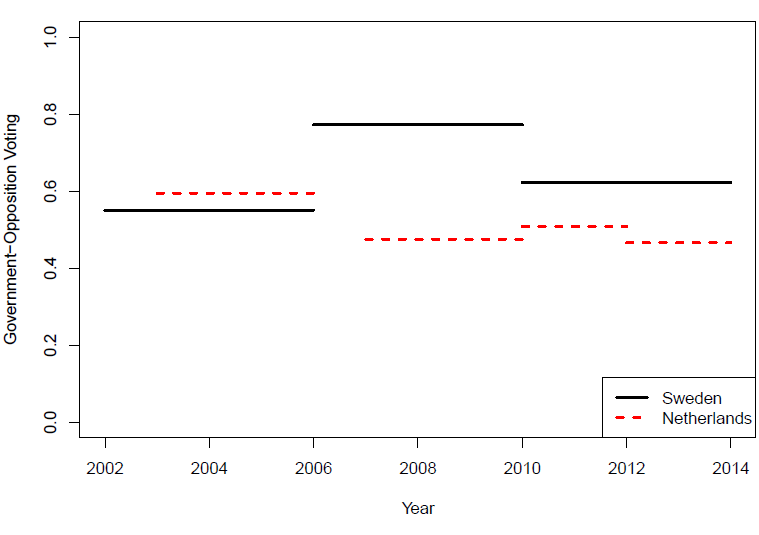

Our results confirm the importance of coalition politics for parliamentary voting behaviour. Figure 1 presents the average levels of voting along government-opposition lines in each parliamentary term. Values of one represent the extreme case where (all of) the government parties always vote differently from (all of) the opposition parties. A value of zero would indicate that there is no relationship between how parties voted and whether they are in government or opposition. We can see that voting in Sweden (black line) is, on average, more adversarial than in the Netherlands (red dotted line). While Swedish minority governments, such as the 2002-2006 Persson government, are more consensual, the levels of government-opposition voting are on average higher than in the Netherlands. These findings are confirmed in a more advanced statistical analysis, which also take into account the left-right position of the government as well as how divided government parties are on the issue that is voted on.

Figure 1: Voting along government-opposition lines in Sweden and the Netherlands

Our analysis confirms that traditions of wholesale or partial alternation in government are important for how adversarial parliamentary politics is. The Swedish tradition of bloc politics results in more ideologically extreme governments than consensus politics in the Netherlands. This, in turn, impacts on how often government and opposition parties vote alike in parliament. When trying to understand how MPs behave in the parliament; the nature of government formation is crucial.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Tom Louwerse is Assistant Professor in Political Science at Leiden University, the Netherlands.

Simon Otjes is researcher at the Documentation Centre Dutch Political Parties of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

David M. Willumsen is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Munich, Germany.

Patrik Öhberg is Assistant Professor in Political Science at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Research from Sweden & the Netherlands shows that ‘bloc’ politics leads to more adversity in legislatures https://t.co/BOfgrC47cq

Research from Sweden and the Netherlands shows that ‘bloc’ politics… https://t.co/yzs73IXLys https://t.co/GzWVqrLeoO https://t.co/Wa7T4ppgoU

[BLOG] Looking at a #Swedish example: How party groupings in #parliament can affect adversity. @democraticaudit https://t.co/1UjICIPeD8

‘Bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/uLb1jRjkwM

Research from Sweden & the Netherlands shows ‘bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/Ii5CgaVr3j

‘Bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/mOOWMw5Tsn https://t.co/LTj0CtegAg

Research from Sweden & Netherlands shows that ‘bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/0Xa0rw4DSO

‘Bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/ejtHGtNI4a

Research from Sweden and Netherlands shows bloc’ politics leads to a greater degree of adversity in legislatures https://t.co/og6jZO859r

Research from Sweden and the Netherlands shows that ‘bloc’ politics leads to a greater… https://t.co/oAYOtXRIuZ https://t.co/vdYfFOYBpT