MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers

In the UK, the legislature and government are fused, with MPs making up the vast majority of ministerial positions (and members of the House of Lords the rest). Here, Resul Umit examines the relationship between the size of that MP’s majority, and likelihood that they will hold ministerial office, finding a strong correlation.

Stephen Timms, MP for the very safe East Ham seat (Credit: Financial Times, CC BY 2.0)

Voters elect their members of parliament (MPs) in general elections, but a large majority of MPs have very little to do with the day-to-day governing of the country. It is rather the ministers in government, as selected by the victorious party leaders, who do. Hence there is an obvious link between the general elections and government formation with regard to who selects ministers. In a recent study with Elad Klein, we show that there is another—albeit a less obvious—connection in terms of who gets selected as ministers; MPs in electorally safe seats are more likely to become ministers.

This is based on an analysis whether the constituency results from the elections to the House of Commons over the period 1992–2015 influenced the likelihood of MPs being selected as ministers in the United Kingdom (UK). The House of Commons provides the perfect case to assess the electoral connection of ministerial selection due to the single-member districts, large government size, and the relatively decentralised candidate selection process in the UK.

Electoral safety affects the ministerial selection because elections are a constraint over the preferences of MPs and their parties. MPs need to stay in the parliament by being re-elected to be able to pursue other goals, including attaining promotion to government ranks. On the other hand, party leaders need to maximise the number of their MPs in order to stay in the government to achieve their policy ideals.

Electoral constraints differ with the marginality of seats for each MP in Westminster systems. In single-member districts, it is comparatively clear to members and to their leaders how electorally safe their parliamentary seats are. As the electoral marginality of a seat increases, or in other words as the number of votes separating success from failure to secure a seat decreases, re-election becomes the dominant motivation.

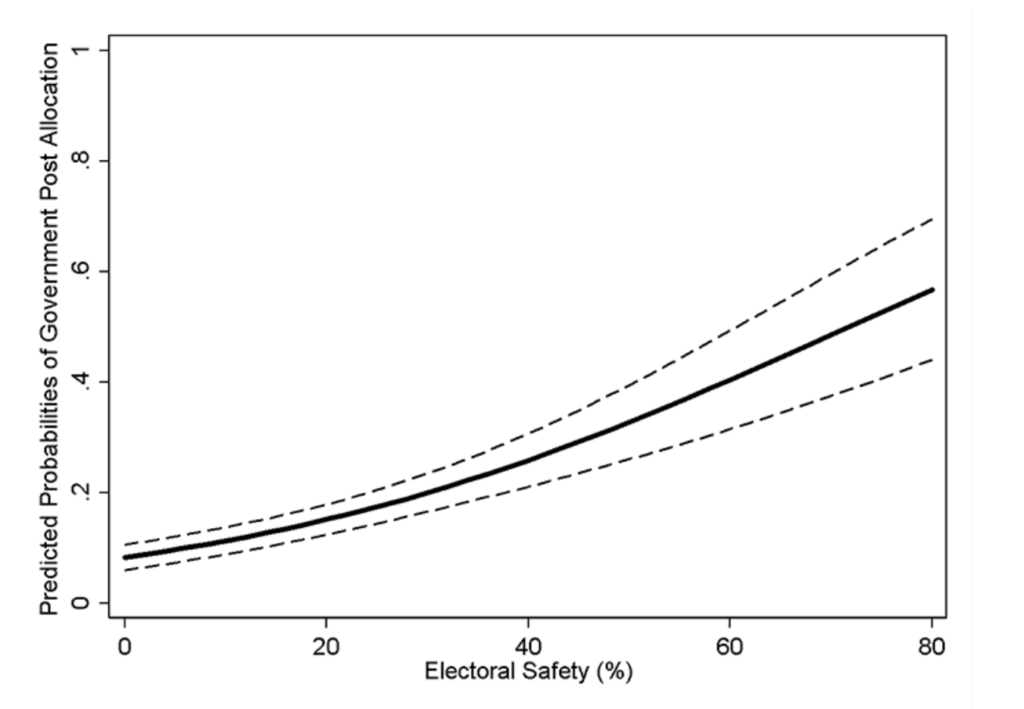

Our results show that there is indeed a positive relationship between MPs electoral safety and their probability of securing a ministerial office. The figure below plots the predicted probabilities of government post allocation across the different degrees of electoral safety, where dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence interval around the fitted line. For an MP with 5% electoral safety, which is often considered as marginal, the probability of becoming a minister is one in 10. In contrast, a 35% majority more than doubles this probability for MPs.

There are at least two important implications of this result. First, if electoral safety increases MPs’ chances of becoming ministers, electorates can affect not only who selects the ministers but also who get selected as ministers. Second, if MPs and party leaders prioritise electoral safety before ministerial office, the results also mean that there is an empirical evidence for the hierarchy of legislative goals—an important theoretical assumption in rational approaches to legislative behaviour.

Electoral safety is particularly important for junior MPs to become ministers. Once they spend long enough in parliament, which roughly 20 years according to our results, electoral safety does not significantly affect their chances of entering the government anymore. Senior MPs enjoy the reputation that they have built in time among their constituents, and those who have done so can then spend more resources on other goals, such as attaining a ministerial office, and less on the goal of re-election. Think about for example a senior MP with 30 years’ experience in the parliament. She is less likely to be alarmed about a 5% electoral majority than a newly elected MP. The former is less likely to feel unsafe with the same amount of a cushion of votes, and therefore more likely to go for a ministerial position with all the experience that comes with seniority.

A risk of linking election results to ministerial selection is that the causality might run in either direction, depending on the candidate selection processes in political parties. If party leaders in the UK “parachuted” their would-be ministers to safe seats before general elections, it would not be meaningful to talk about any effect of electoral safety on ministerial selection. However, the effect of electoral safety continues to hold among those MPs who lost an election before entering the parliament. It is reasonable to assume that such MPs, who had unsuccessful attempts at being elected, were not centrally posted to these constituencies become ministers later on.

One of the other controls in the study relates to gender. On the one hand, as evident in the increasing but still unfair share of female MPs in the House of Commons, female citizens are less likely to become parliamentary representatives. Those females who make it to the parliament, on the other hand, are more likely to become ministers according to the results. This confirms the commitment of political parties in the UK to increase women’s representation in government.

—

Note: This article is based on Resul Umit’s co-authored paper with Elad Klein in the Journal of Legislative Studies (free access). It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—-

Resul Umit is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna. He tweets at @ResulUmit.

Resul Umit is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna. He tweets at @ResulUmit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers https://t.co/TgX60sSPX6

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers https://t.co/TY0MchPPyQ

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers https://t.co/6WBpECkhTS

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers https://t.co/G7HFchy0w1

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers: https://t.co/dq4yHnLMKX

MPs in safe seats are more likely to become ministers https://t.co/7BKeEQgaSo

@PJDunleavy @democraticaudit Stands to reason,why give a fly-by-night a long-term position? And this needed a study?