Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is

In his new book, Richard English attempts to answer a question many would prefer not to contemplate: does terrorism work? Are its perpetrators right to judge that the only way to achieve the changes they want is through violence? English goes on focus on four of the most significant terrorist organisations of the last half-century: al-Qaida, the Provisional IRA, Hamas, and ETA. This extract confronts the difficult truth that terrorists tend to show the same levels of rationality as other people.

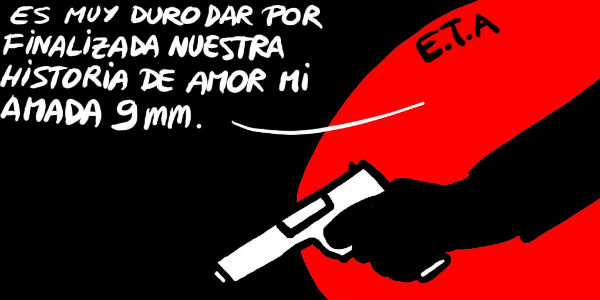

ETA: “It’s tough to end our love affair with my 9mm.” Image: Paco Rives Manresa via a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

In the heart of Oslo, on the site where on 22 July 2011 Anders Behring Breivik exploded a van-bomb killing eight people at government buildings, the Norwegian state has established a dignified Centre commemorating the events of that terrible day. Breivik himself – a would-be crusader against what he took to be pernicious Norwegian multiculturalism and an increasing Muslim presence in the country – has been lengthily and deservedly imprisoned. And the 22 July Centre offers an elegiac window onto his atrocity. There are agonisingly silent photographs of most of the 77 people he killed (after Oslo he murdered a further 69 victims later the same day, at the Norwegian Labour Youth League’s summer camp on beautiful Utoya island). And there is the actual wreckage of the van in which his Oslo bomb had been planted: a gruesome, mangled, sculpture-like relic of his blood-stained work.

It is hard not to be moved by the quiet gesture embodied in this 22 July Centre. But as I myself walked around it I was struck again – as I frequently had been while living for many years in violence-torn Belfast – that behind all such recollections of terrorism lies a question of very high importance, which we have none the less found it difficult to address adequately in relation to actions such as Breivik’s famous operation. For all of its baneful effects, Does Terrorism Work?

It’s an important, controversial, and difficult question. I think it’s also one which requires an historically-grounded answer, and a carefully-crafted framework for assessment, if we are to address it as seriously as it deserves.

The question is important both analytically and practically. Any full understanding of a phenomenon which – like terrorism – is focused on the pursuit of political change, will necessitate analysis of how far such change has actually been achieved. In the case of terrorism, this issue is even more analytically important given its implications for explaining some of the central dynamics of terrorist activity: its causation (why does it occur where and when it does?); its varying levels across place and time (why does it endure for the periods and at the specific, differing levels that it does?); the processes by which terrorist campaigns come to an end (why does it dry up in some settings at some moments, but not in and at others?); and the patterns of support involved in terrorism (why are some people more likely to endorse and practise it than others?).

Anders Breivik in court. Photo: Day Donaldson via a CC BY 2.0 licence

Despite the doubts of some, a persuasive body of scholarly literature now suggests that those who engage in and support terrorism tend to display the same levels of rationality as do other people; that they tend to be psychologically normal rather than abnormal; that they are not generally characterised by mental illness or psychopathology (indeed, anyone who has met and got to know large numbers of people who have been involved in terrorist campaigns can testify to their striking normality). The argument here is not that terrorists act out of rationality alone, but rather that their decision-making processes are likely to be as rational as are those of most other groups of humans, and that even a seemingly incomprehensible act such as suicide bombing can be judged to be, at least in part, rationally motivated.

This being so, the emergence and sustenance of terrorism centrally rely on the fact that perfectly normal people at certain times consider it to be the most effective way of achieving necessary goals. Since most people would probably prefer not to be engaged in violence than to be engaged in it, and would probably prefer peace to war, what has frequently happened is this: some people have judged terrorism to be necessary because they think their goal sufficiently important for it to be pursued through these violent means, and further think that it would be unattainable without them.

But if we are properly to understand the processes of non-state terrorism, then it is not enough to acknowledge that it occurs when sufficient numbers of people sincerely consider it likely to work, or when they believe it to be the only means of achieving change; nor is it enough for us to recognise that some forms of terrorist activity rather than others will occur because these particular forms are judged more likely to succeed in certain contexts (suicide bombing, for example, often being deployed when other violent tactics have been perceived to fail); nor should we merely judge that terrorism is likely to dry up when enough of its adherents reject the view that it is the best way to achieve change. We need also to assess whether or not non-state terrorists are in fact right to consider this method to be the most efficacious way of achieving their various political goals. The issue of justifying the use of violence remains rightly prominent and complex. With respect to such assessments in relation to terrorism, we need to know how far and in what ways terrorism actually works (or does not) in historical and political practice, and the precise dynamics that have been involved. If we want fully to understand terrorism analytically then we need not only to identify what people think to be the case, but also to assess systematically what has actually been the historical reality. So this book offers a political historian’s answer to the question, does terrorism actually work?

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is an extract from Does Terrorism Work?, published by Oxford University Press.

Richard English is Pro-Vice Chancellor for Internationalisation and Engagement at Queen’s University Belfast, where he is also Professor of Politics, and Distinguished Professorial Fellow in the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice. Between 2011 and 2016 he was Wardlaw Professor of Politics in the School of International Relations, and Director of the Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of eight books, including Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (2003) and Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland (2006).

Richard English is Pro-Vice Chancellor for Internationalisation and Engagement at Queen’s University Belfast, where he is also Professor of Politics, and Distinguished Professorial Fellow in the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice. Between 2011 and 2016 he was Wardlaw Professor of Politics in the School of International Relations, and Director of the Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of eight books, including Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (2003) and Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland (2006).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/VQqpGte3v9

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/BCNm5nyhOw

We need to know how far and in what ways terrorism actually works (or doesn’t) in historical and political practice https://t.co/JEToEmSuX1

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/JEToEmSuX1

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/BCNm5nPSG4

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/8iKULniXMx

Does terrorism work? Why we need to answer the question – however difficult it is https://t.co/16TDcgogar https://t.co/57UVqbXdOa