Women are still outnumbered on Commons select committees

Figures from the Select Committee Data Archive Project reveal that women are still outnumbered on Commons select committees, despite a steady increase of female MPs in Westminster. Sophie Wilson looks at the numbers on gender balance of select committees since 1979 and what they mean for parliamentary scrutiny.

MPs Tessa Munt and Craig Whittaker during an Education Select Committee visit to Leicester. Photo: UK Parliament/ Catherine Bebbington via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

The UK ranks 48th in the world for parliamentary representation of women, a state of affairs, Maria Miller MP, Chair of the Commons Women and Equalities Committee, recently described as “shockingly low”. As the committee argued in a report on women in the House of Commons after the 2020 election, the number of female MPs in Parliament matters. So does the number of women elected or appointed to positions of responsibility within Parliament, whether as Cabinet members, shadow ministers or select committee chairs.

Women have been consistently under-represented amongst select committee chairs.

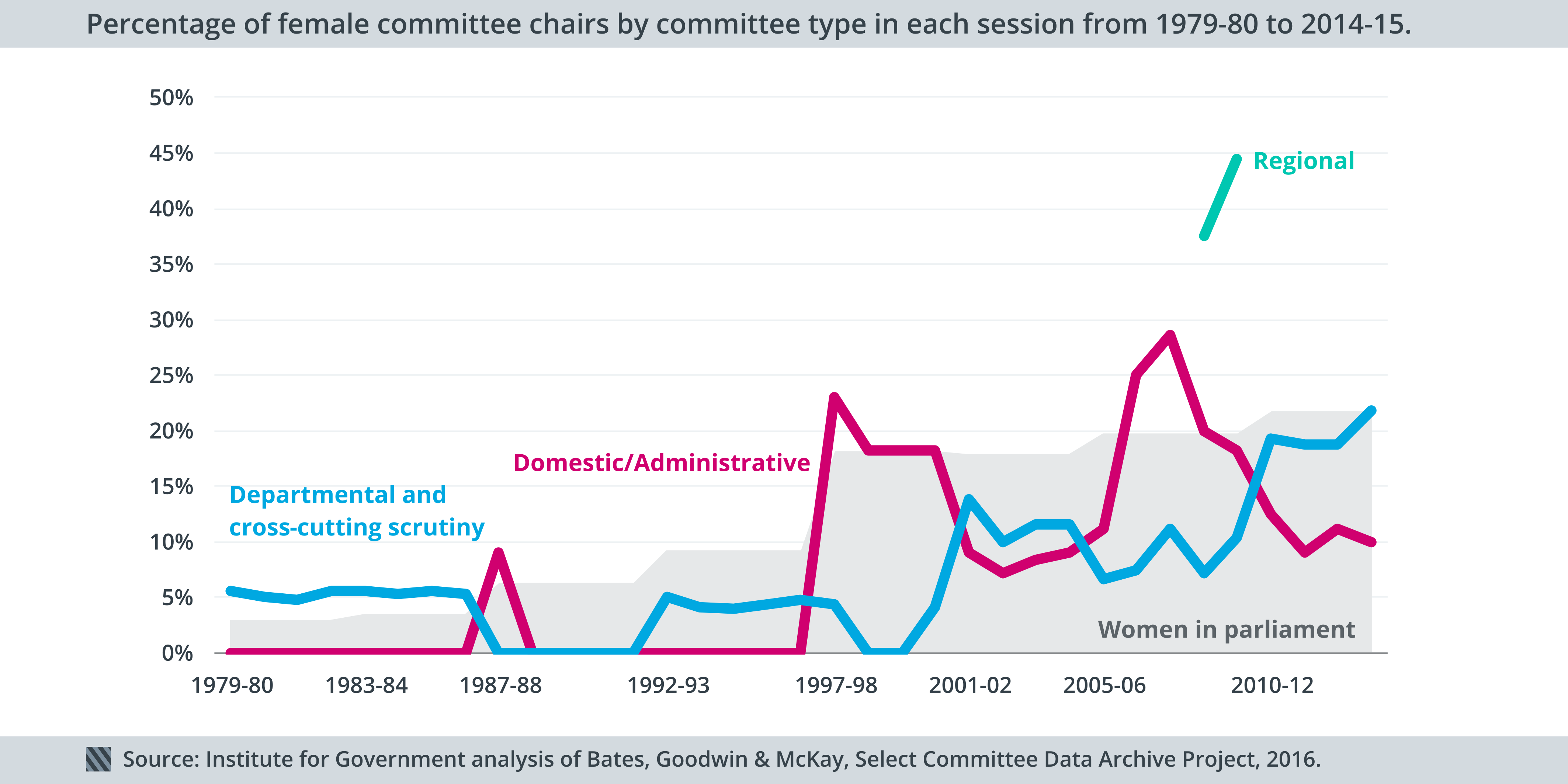

Since 1979, the percentage of female chairs on committees has usually been smaller than the percentage of women in Parliament. The main exception to this was during the brief existence of the regional committees created by the Labour Government between 2009 and 2010. The chairs of these committees were more balanced in gender terms compared to other select committees or Parliament as a whole, with between 45% and 55% being female.

Although progress is slow, the overall number of female chairs across the committee system has gradually increased due to a cohort effect, as the percentage of women in Parliament has increased. This is important because the role of a select committee chair is a high profile, influential one; an increase in the number of female chairs has a direct impact on the visibility of women in Parliament, and may encourage more women to play a role in the committee system and politics itself.

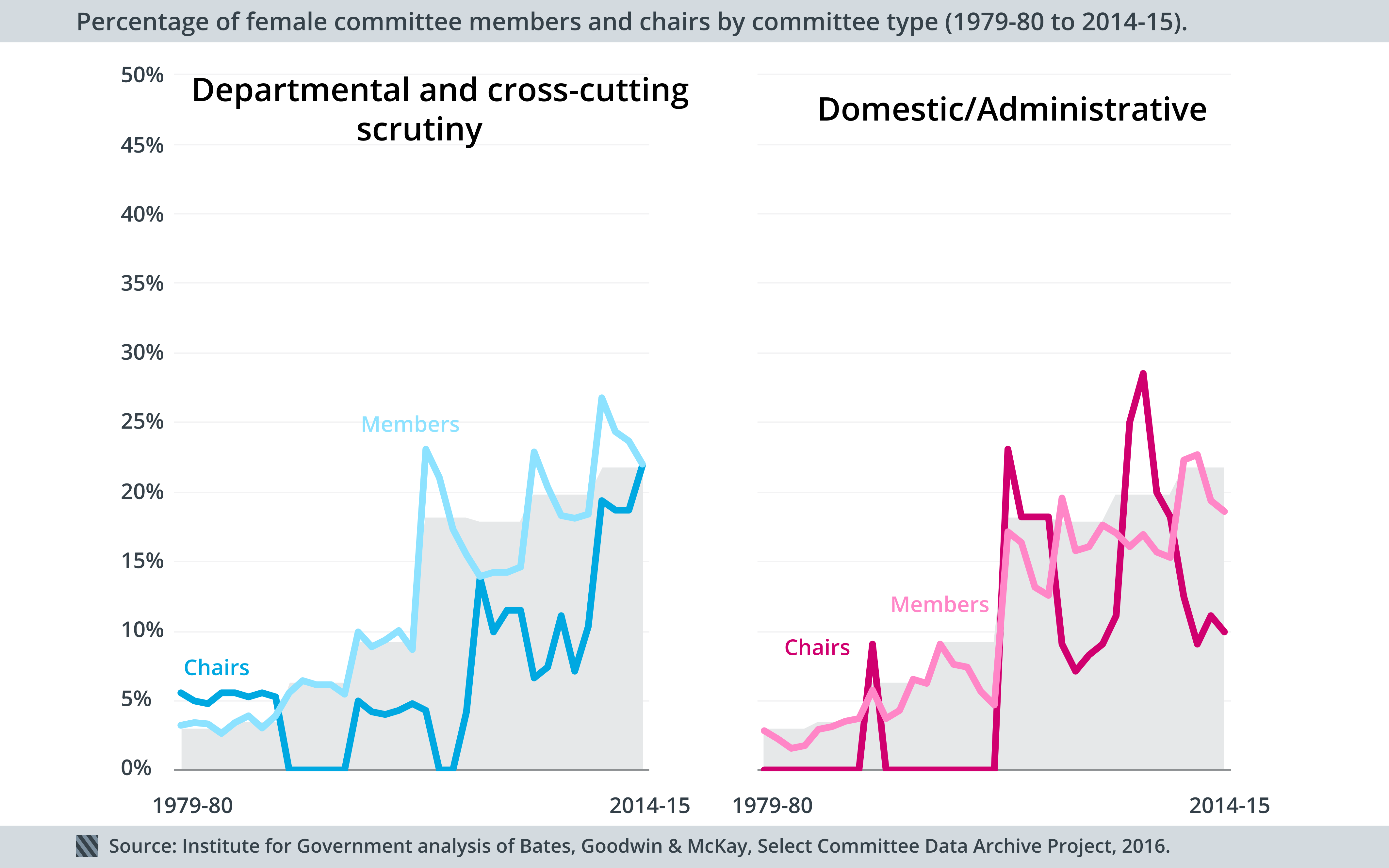

The gender balance of committee members has tended to align more closely to that of the House.

In two-thirds of Parliaments since 1979, departmental and cross-cutting scrutiny committees began with a higher percentage of female members than the House as a whole. This percentage often then dropped off over the course of a Parliament, possibly as newly elected female MPs were recruited to front bench roles having demonstrated their ability on committees.

Domestic and administrative committees have tended to have a lower percentage of female members compared to departmental and cross-cutting scrutiny committees. On the other hand, a higher percentage of domestic and administrative committees have been led by female chairs.

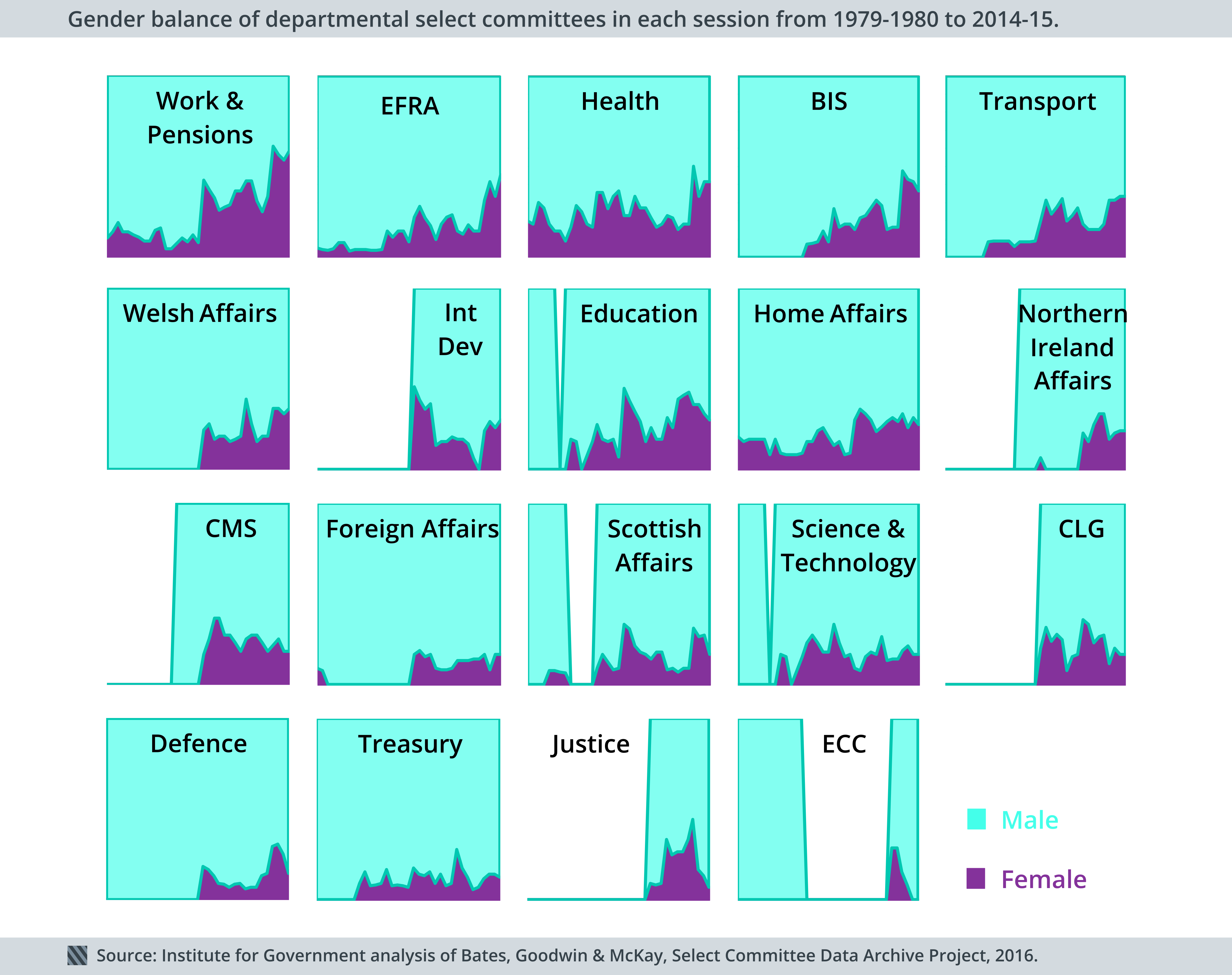

Some committees have a better track record on gender balance than others.

Since 1979, more female MPs have sat on the Work and Pensions, Environment, Food and Rural Affairs or Health committees than any others. Only 33 women (out of a total of 446 MPs) have sat on the Defence Committee and only 32 women (out of a total of 431 MPs) have been a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee since first being established 36 years ago. This means women MPs made up only 7% of members on both committees during this period.

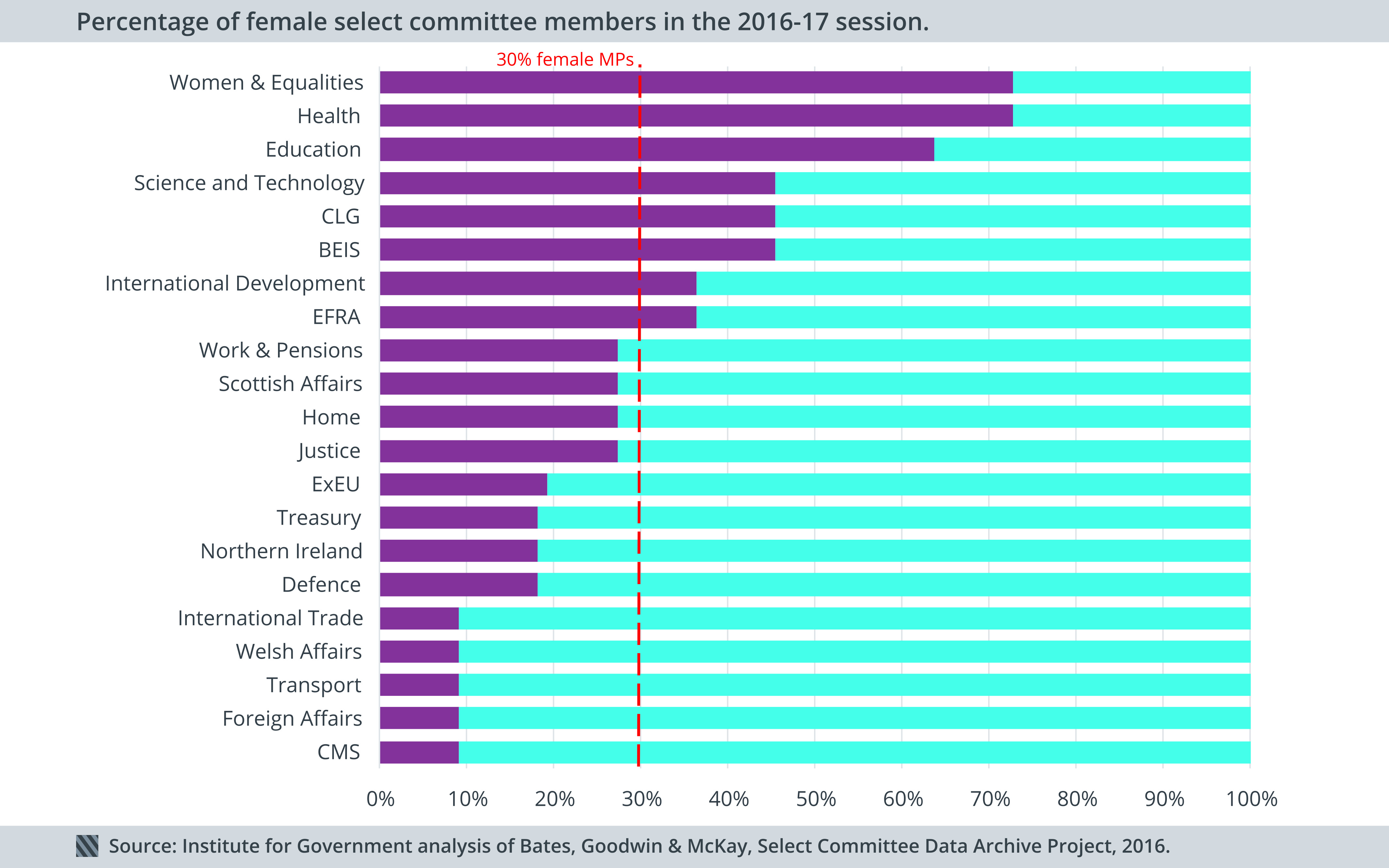

The two newest committees – Exiting the EU and International Trade – both have poor representation of women compared with the Commons as a whole.

Despite the steady increase in the number of female MPs across the committee system, the two most recently created select committees – the International Trade and Exiting the European Union committees – both have male chairs, and their members are predominantly male. Both fall in the bottom half of committees when ranked by their gender balance. The International Trade Committee only has one female member, making it one of the worst committees in terms of gender balance in the House.

Not only does this situation reflect poorly on the role of women in Parliament, but it also risks undermining the effectiveness of both committees in holding the Government to account on Brexit. Women can bring a different style and set of experiences to the scrutiny process which could be missed. More representative scrutiny is likely to result in better scrutiny. Although the gender balance of select committees has improved since 1979, there is clearly more to be done.

This analysis is based on data provided by Stephen Bates (University of Birmingham), Mark Goodwin (University of Birmingham) and Steve McKay (University of Lincoln), as part of their Select Committee Data Archive Project, part-funded by the British Academy and the University of Birmingham’s British Politics Research Group. The Select Committee Data Archive Project covers all Commons committees for parliamentary sessions from 1979-80 to 2014-15.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It was first published at the Institute for Government blog.

Sophie Wilson is a researcher at the Institute for Government. Previously she was based in the Engagement Team at the Office for Public Management, working on a range of projects seeking to improve the delivery of public services.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.