‘Conceived in Harlesden’: When do candidates emphasise their local connections in UK general elections?

The personal characteristics of election candidates matter to voters. With election leaflets representing the most common form of contact voters have with Prospective Parliamentary Candidates (PPCs), when do leaflets emphasise a candidate’s personal traits and/or local connections? Caitlin Milazzo and Joshua Townsley use a dataset of more than 3,700 leaflets distributed during the 2015 and 2017 general elections to explore the conditions under which the personal characteristics of candidates appear in election communications.

Picture: John McGarvey via a (CC BY-NC 2.0) licence

Despite the increasing focus on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, leaflets remain the most common form of contact that voters have with politicians during an election campaign. Parties also spend substantial sums on leaflets and direct mail. According to the Electoral Commission, prior to the 2015 and 2017 general elections political parties spent more than £15 million and £13 million respectively on communications sent to voters via post. While there is evidence that leaflets can increase turnout, less attention has been paid to the messages they contain.

Leaflets frequently talk about various local and national policy issues – everything from potholes to defence and the economy. But there are also strong incentives for candidates to talk about themselves. We know that voters value certain traits in their prospective representatives – studies consistently show that localness is a vote-winner. If candidates can talk up their personal story, there could be votes in it for them. So what factors explain whether a leaflet is likely to emphasise a candidate’s personal characteristics?

To find out, we manually coded thousands of leaflets that were uploaded to the crowdsourced archive of political leaflets ElectionLeaflets.org. The site is run by the non-partisan Democracy Club, and encourages users to photograph leaflets they receive during election campaigns and upload them to their archive. We studied general election leaflets delivered by candidates from Britain’s six largest parties: the Conservative Party, the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats, the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the Green Party and the Scottish National Party (SNP).

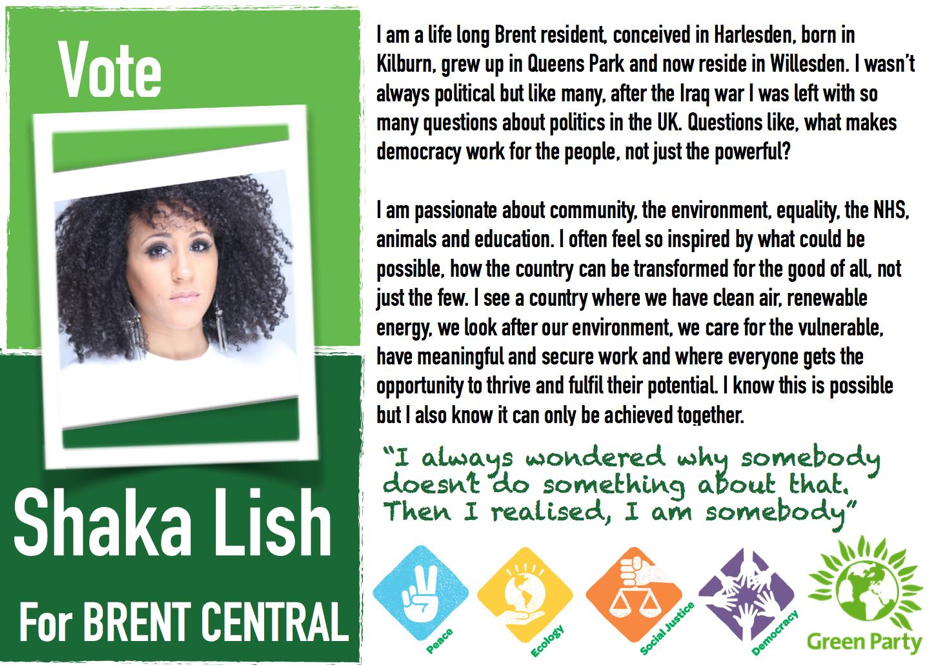

Our aim was to identify two types of candidate-centred messaging. First, we look at whether a leaflet mentions any connections the candidate has to the local area – that is, their ‘local ties’. This could include, for example, mentions that they live in the constituency or that their kids go to local schools. The 2017 Green candidate in Brent Central, for instance, went as far as to mention that she was ‘conceived in Harlesden’. Second, we identify whether the leaflet mentions any of the candidate’s traits or characteristics (for example, their occupation or education). UKIP’s 2017 candidate in South Thanet, for example, mentioned his years of service with the army, his experience in marketing, as well as the fact that he is an ordained minister.

Source: Green Party, via Electionleaflets.org

In some cases, leaflets mentioned both local connections and traits. For example, a 2017 Lib Dem leaflet in Erewash noted that ‘Martin is the Chair of Governors at Friesland School in Sandiacre where he has served as governor since 2002’. In this case, the candidate is emphasising both his occupation and his local connections, as the school in question is located within the constituency.

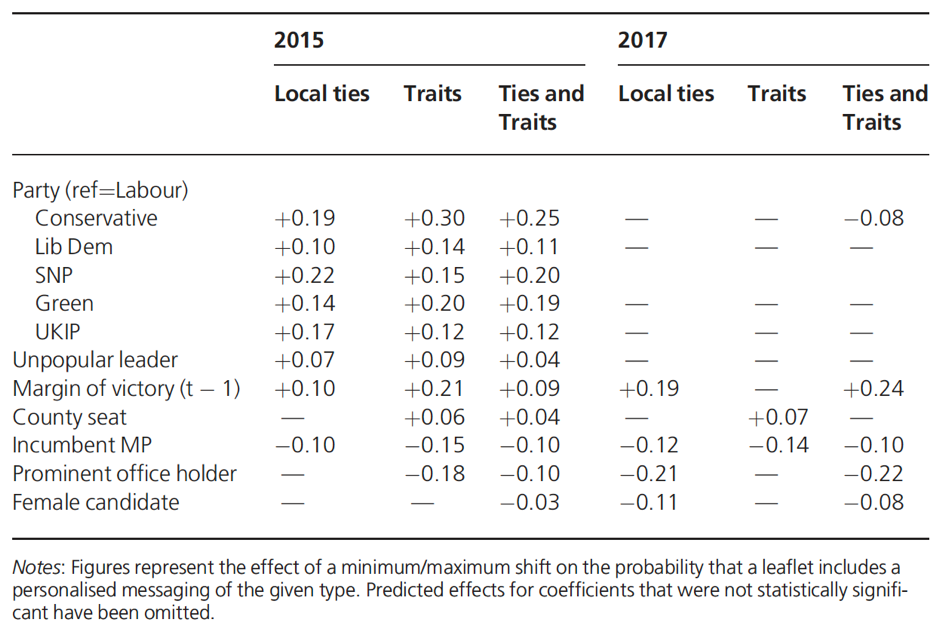

Having coded our leaflets, we used logistic regression models to determine the effect of a series of factors on whether or not a leaflet contained at least one reference to the candidate’s local connections (model 1), the candidate’s traits (model 2), or both (model 3). The results of these models are below.

We find systematic variation in leaflet personalisation across political parties. In 2015, for instance, Labour leaflets were less likely to mention candidates’ local connections, traits or both than those from all other major parties. However, in 2017, leaflets from Labour candidates were more likely to contain candidate-centred messages than those from Conservative candidates. This echoes what we know about the Conservative campaign in 2017, which focused far more on Theresa May and national issues such as Brexit.

Beyond party differences, contextual factors also matter. Leaflets distributed in ‘safe’ seats were more likely to contain personal messaging than those distributed in ‘marginal’ seats. Leaflets were also more likely to include personal messages if the candidate’s party leader is unpopular with their constituents. Leaflets delivered in rural constituencies were also more likely to contain mentions of a candidate’s personal background.

Finally, leaflets from certain types of candidates were more likely to contain personal messages. Leaflets from incumbent MPs were less likely to contain such messages than those from ‘challengers’ – perhaps because sitting MPs are more well-known than challengers, who need to make greater efforts to get ‘their story’ across. Similarly, leaflets from candidates who hold prominent political office (such as members of the cabinet or shadow cabinet) were less likely to include personalised messages. Interestingly, we also find evidence of a gender effect. Leaflets from female candidates were less likely to talk about the candidate’s personal story.

Overall, we find that whether or not a leaflet contains personal information about a candidate (beyond just their name) is largely a function of party differences. In 2015, we find evidence that leaflets from Labour were less likely to contain messages about a candidate’s local ties and/or traits than those from the Conservatives. By 2017, however, we find the reverse. This gives rise to the question: was the Conservatives’ decision to run a more leader-focused campaign in 2017 (and focus less on their candidates’ characteristics) related to their surprising underperformance?

But beyond party differences, we also find that contextual and candidate-level factors also have an effect. Taken together, our findings suggest that voters in certain types of seats are more likely to receive personal information about their candidates. This is important, as such voters could be ‘primed’ to think about personal characteristics when deciding how to vote.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

This article is based on the authors’ paper, ‘Conceived in Harlesden: Candidate-Centred Campaigning in British General Elections’, forthcoming in the journal Parliamentary Affairs.

About the authors

Caitlin Milazzo is Associate Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She tweets at @CaitlinMilazzo.

Caitlin Milazzo is Associate Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She tweets at @CaitlinMilazzo.

Joshua Townsley is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of Kent. Joshua also runs the LSE’s Democratic Dashboard voter information project. He tweets @JoshuaTownsley.

Joshua Townsley is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of Kent. Joshua also runs the LSE’s Democratic Dashboard voter information project. He tweets @JoshuaTownsley.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.