National parliaments are not the losers of EU integration – at least not anymore

Eurosceptics like to argue that Parliament has become in part redundant following transfers of power from the national to the European level. Katrin Auel, Olivier Rozenberg, and Angela Tacea argue that contrary to this, national parliaments in Europe have not become inconsequential in making policy at the European Union level in the wake of the Lisbon Treaty, and that they remain key decision makers.

National parliaments, it turns out, are not the poor losers of EU integration – at least not anymore. A recent comparative study shows that they are in general rather active in EU affairs. This is all the more the case, where they are in a strong institutional position in EU affairs. In addition, their activities vary depending on the parliamentary function they emphasise most.

Over the course of EU integration, national parliaments have undergone a profound process of formal Europeanisation and are now generally in a much better position to become involved in EU affairs. This adaptation has also followed roughly similar institutional patterns. National parliaments have all established specialised committees – the European Affairs Committees (EACs) – and they have obtained extended rights to be informed about and to give their views on European legislative proposals.

Yet the question to what extent parliaments actually make use of their better formal position still remained open, especially given that MPs are well known for not regularly using all the weapons in their armoury. We therefore analysed the parliamentary EU activities across all 27 national parliaments in the EU between 2010 and 2012. This included mandates and resolutions as well as opinions within the Political Dialogue to capture the parliamentary policy influencing function; the time spent in EAC meetings to include the ‘working’ aspect of national parliaments that relates to scrutiny and developing expertise in EU affairs; and plenary debates, to measure the extent to which parliaments fulfil their communication function. Finally, we also include reasoned opinions on a breach of the subsidiarity principle, introduced by the Lisbon treaty, to complete the picture.

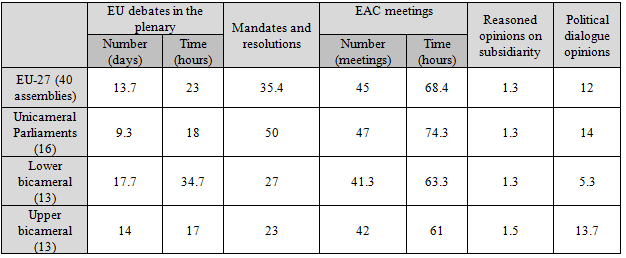

Table 1:Parliamentary EU activities: Average by assembly by year, 2010–2012

As indicated in the table, European activities are far from being marginal in parliaments. On average, their EACs met more than once per working week for over one hour, and chambers issue nearly 50 European statements per year: 35 addressed to the government and twelve to the European Commission. The Early Warning Mechanism, however, has been used in a very limited way – putting the noise made about this new instrument in sharp contrast to its rather toothless nature.

Although generally active, parliaments differ greatly when it comes to EU activities the number of resolutions passed by individual parliaments ranges from 0 to 220 per year over the three years. Similarly, the duration of plenary debates spent on EU issues ranges from 0 to over 112 hours, the number of opinions from 0 to 197. Overall, unicameral parliaments perform better regarding all kinds of written opinions but are less active on the floor then lower bicameral assemblies.

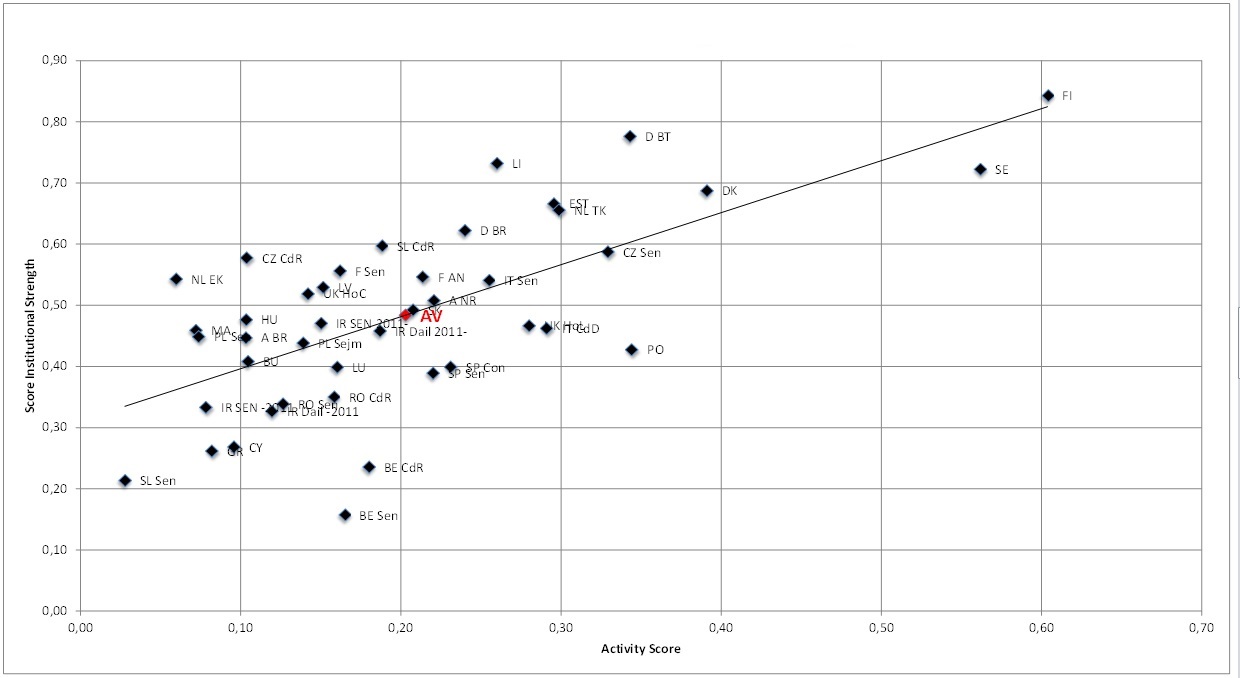

How can we explain these differences in the parliamentary involvement in EU affairs? The location of each of the 40 parliamentary chambers according to both their institutional prerogatives and their average level of activity shows a strong correlation between their formal position and their involvement in EU affairs.

Figure 1: OPAL scores: institutional strength vs activity

Note: based on data for all 40 parliamentary chambers of the national parliaments, AV indicates the average scores for institutional strength and activity.Indeed, this figure clearly indicates that parliaments that are strong ‘on paper’, such as those of Sweden and Finland or, to a lesser extent, Denmark and Germany, are also more active on EU issues in their day-to-day business. Likewise, ‘scrutiny laggards’ perform poorly on both dimensions. This may be regarded a significant contribution for the endless debate over the extent of the EU’s de-parliamentarisation and possible remedies: parliamentary chambers that have strong participation rights in EU affairs also make, on the whole, active use of them.

At the same time, this result raises rather than answers the question of why parliaments are actively involved in EU matters, and in such different ways. Some are fairly active regarding all types of activities (Swedish Riksdag or Finish Eduskunta) but most tend to specialise on specific parliamentary functions in EU affairs, such as controlling their governments through resolutions (Danish Folketing), organising floor debates (German Bundestag, Czech Senate), or engaging in the political Dialogue with the European Commission (Italian Senate, Portuguese Assembleia).

In order to understand this ‘instrument mix’, we tested a number of explanations from the literature on the Europeanisation of national parliaments: the strength of parliament independently of EU affairs, the type of political system (consensus vs. majority), Euroscepticism in public opinion and among elites, and the degree of conflict over European integration between the governing and opposition parties. In addition, we looked at the salience of EMU issues as the 2010-12 period marked the most turbulent time of the eurozone.

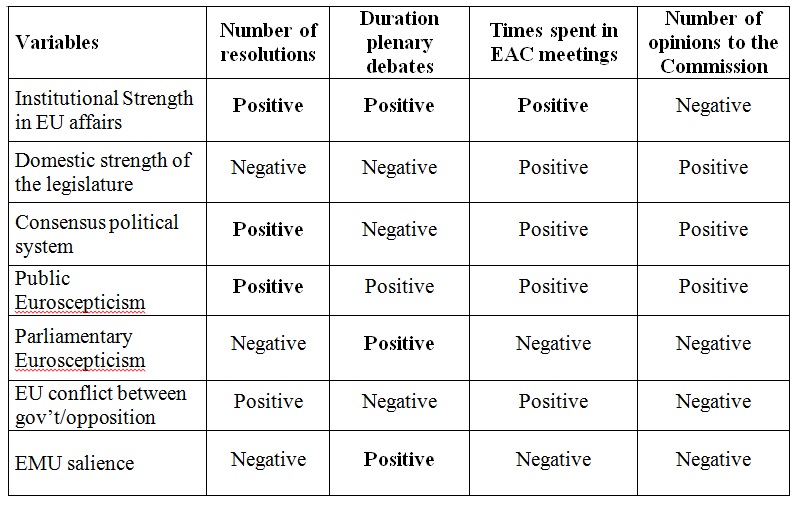

Table 2: Simplified presentation of the statistical results

Note: statistically significant impact in bold, analysis of lower chambers onlyThe table indicates that the variables likely to explain why parliaments are active in EU affairs vary between different types of activity. The number of resolutions sent depends mainly on the institutional features of the political systems, whereas communication activities such as floor debates are sensible to contestation of the EU, especially MPs Euroscepticism and the salience of the EMU within a given country. Those contrasting results indicate not only that the activities are related to specific ends, but also that some chambers tend to specialize according to those functions. Some aim at scrutinizing their government, others at influencing it and again others at communicating those issues to the public. And most of the chambers are just not powerful (or brave) enough to pursue all those ends simultaneously.

Last but not least, two types of activities in our sample remain largely unexplained, namely the time MPs spend in meetings of the European Affairs Committee and their engagement in the political Dialogue. Missing explanatory links here could be the importance of general institutional rules and routines of parliaments, on the one hand, and the effectiveness of the instruments, on the other. Indeed, the next step after stating that parliaments are actively involved in EU affairs is to assess whether they are also successfully involved. Our data does not allow us to draw conclusion on this key point – except that success should be assessed according to a variety of parliamentary functions, rather than just based on influence in EU policy-making.

—

Note: to see the authors full paper, click here. This post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

|

Katrin Auel is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Vienna. |

|

Olivier Rozenberg is Associate Professor at Sciences Po, Centre d’études européennes in Paris. |

|

Angela Tacea is a Research Assistant at Sciences Po, Centre d’études européennes in Paris. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] This article originally appeared at Democratic Audit, and gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, […]

National parliaments are not the losers of EU integration – at least not anymore https://t.co/U3FPeN6qcm

National parliaments are not the losers of EU integration – at least not anymore https://t.co/cxzotsjDCG