Rules on election deposits create an uneven playing field and protect the interests of the largest parties

Evidence suggests a multi-party system is slowly emerging in UK politics, but our electoral rules may be impeding its development. In the 2012 audit of UK democracy, Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone considered the requirements for candidates to pay a deposit in order to stand for election, and showed how these had a disproportionate impact on small parties.

How do requirements on election deposits affect candidates from smaller parties? Credit: secretlondon123 (CC BY-SA 2.0)

With a number of specific exceptions, all adult British and Irish citizens resident in the UK have the right to stand as a candidate in elections, as do adult citizens of any Commonwealth country with indefinite leave to remain in the UK. Those precluded from standing for election to Parliament, defined by the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975, as amended, include members of the police and armed forces, serving civil servants and judges, members of the House of Lords and those declared bankrupt. Similar provisions apply for elections to devolved parliaments and assemblies and to the European Parliament. There are also a number of specific restrictions for candidacy in local elections relating to connection to the locality and employment in local government.

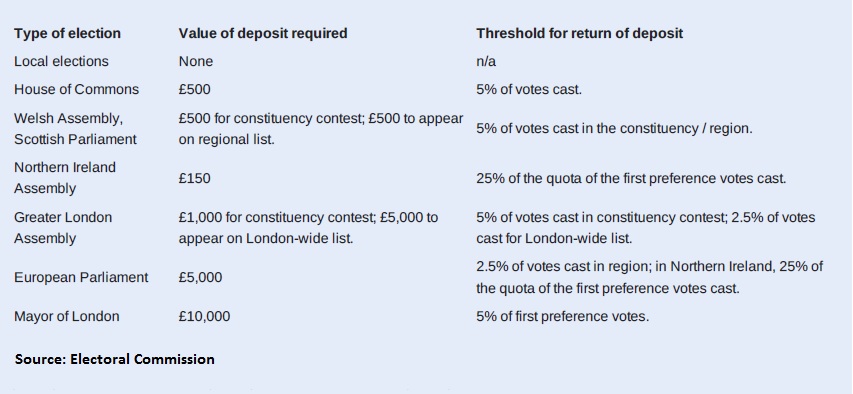

All candidates must be nominated by electors in the district in which they are standing. Where candidates are standing for a political party, that party must be registered with the Electoral Commission, but no such requirement applies for independents. Deposits of £500 must be lodged by all candidates standing for elections to the House of Commons, the Welsh Assembly or Scottish Parliament; with a deposit of £150 for the Northern Ireland Assembly. Higher deposits are required of candidates contesting election for the London assembly (£1,000), the European Parliament (£5,000) and the mayor of London (£10,000). No deposits are required for candidacy at local elections. In all cases, deposits are returnable if the candidate secures more than a specified percentage of the votes cast (see Table One below). There has been a significant growth in the number of lost deposits at recent elections, which has arisen from a sharp increase in the number of candidates fielded by smaller parties. This development is one of several illustrations of how the electoral system interacts with other structural features of UK democracy to create an ‘uneven playing field’ for parties contesting elections.

Table One: Deposits required by candidates in UK elections

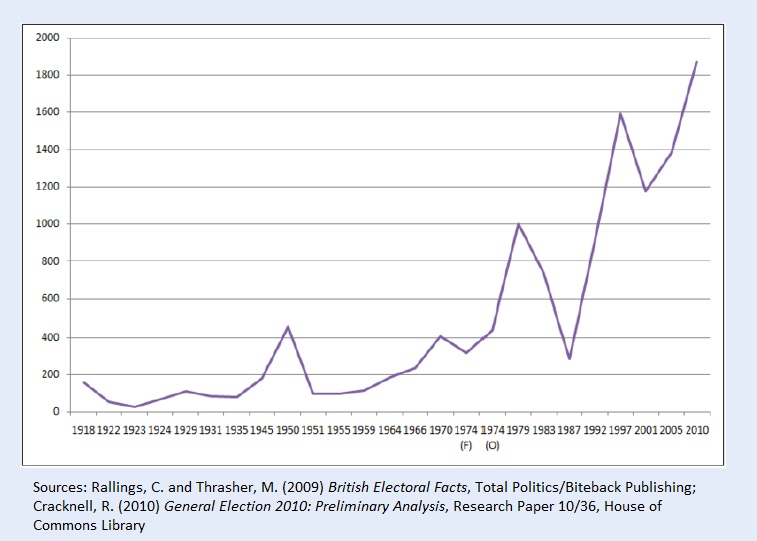

The number of deposits forfeited at general elections has shown a clear tendency to increase over the last century. Figure 2.2d shows that, with the exception of 1950, when the Liberal vote was squeezed dramatically, fewer than 200 deposits were typically lost at elections from 1918-64. Changes in the party system during the 1970s then prompted a sharp increase in lost deposits, leading to a review of the arrangements after the 1983 general election, when 1,000 candidates lost their deposits. After 1985, the value of the deposit was increased from £150 to the current £500, but the threshold which candidates needed to cross to retain their deposit was reduced from 12.5 to 5 per cent of the (valid) votes cast. While these changes prompted the number of lost deposits to fall dramatically to 289 at the 1987 general election, the impact proved to be short-lived. There have been more than 1,000 lost deposits at every general election since 1997, and the 1,873 deposits forfeited in 2010 constituted an all-time record.

Chart One: Number of lost deposits at general elections, 1918-2010

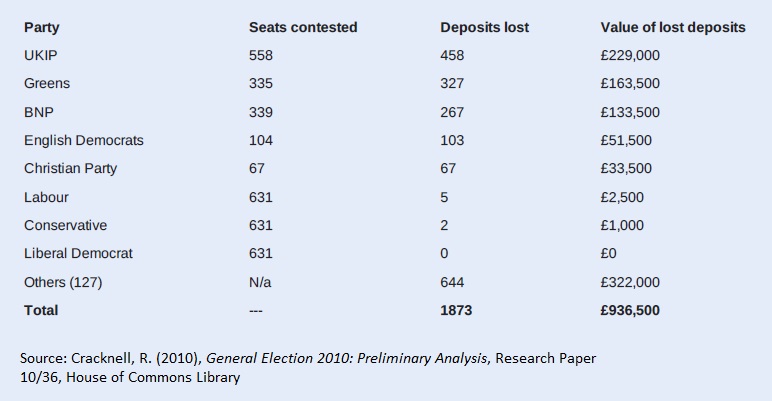

The principal reason for this growth in the number of lost deposits is the rise in the number of candidates standing for smaller parties. In 2010, 458 out of 558 UK Independence Party (UKIP) candidates lost their deposits, as did 327 of the 335 Green Party candidates and 267 of the 335 British National Party (BNP) candidates. The total value of lost deposits in 2010 was almost £1 million, 0.4 per cent of which was accounted for by the three largest parties, but 56 per cent by candidates from UKIP, the Greens and the BNP as the three next largest UK-wide parties.

Table Two: Number and value of lost deposits, by party, 2010 general election

It should, of course, be noted that the £500 deposit entitles the candidate to a freepost allowance, the notional value of which will run to tens of thousands of pounds in the average constituency. Moreover, some may regard deposits as an effective means of preventing ‘extremist’ parties such as the BNP gaining a foothold in British politics. However, in both instances, it is important to examine the long-run trends in lost deposits alongside wider changes in the party system. There is clear evidence of the emergence, albeit suppressed, of a multi-party system in the UK in recent decades. The current rules about deposits for general elections clearly have a disproportional impact on smaller parties – not least because of how they operate in concert with the electoral system to protect the interests of the largest parties. At nine general elections since 1974, the Green (previously Ecology) Party has paid out a total of over £800,000 in lost deposits, measured in 2009-10 prices. UKIP, which secured 3 per cent of the UK vote in 2010, has forfeited almost £900,000 (again measured in 2009-10 prices) in lost deposits since 1997.

The post is based on extracts from the 2012 audit of UK democracy. For further discussion see sections 2.1.3 Candidates and parties: registration and media access and 2.2.1 Forming parties and campaigning

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report.

Shortlink for this post: https://buff.ly/GCMRI8

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.