The 1913 death of Emily Wilding Davison was a key moment in the ongoing struggle for gender equality in the UK

2013 marks the centenary of the death of suffragette Emily Wilding Davison, one of the defining moments of the women’s struggle for the right to vote. In the latest post of our Gender and Democracy series, historian Professor June Purvis looks back at the events of 1913 and considers how far women still have to go to achieve equality.

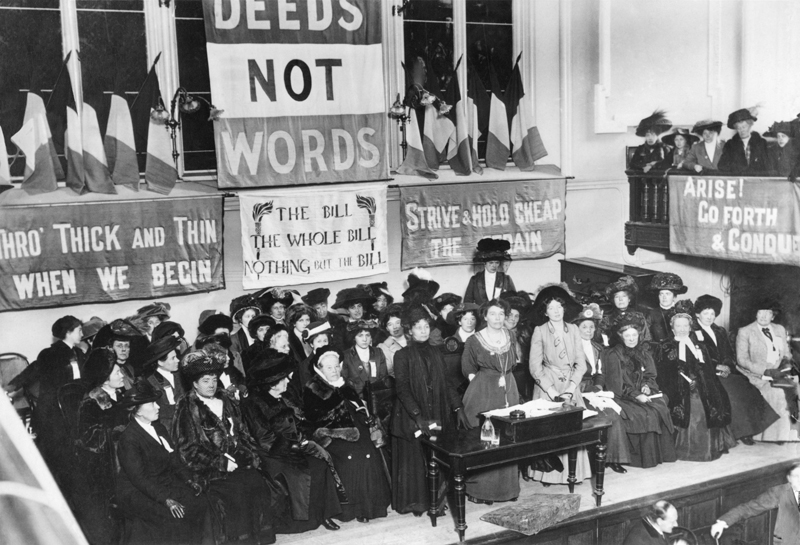

Many of the aims of Emily Wilding Davison and the Women’s Social and Political Union are still relevant today.

2013 is a special year for those interested in the women’s suffrage campaign in Britain and in the development of our democratic system of government. One hundred years ago, on the 8th June 1913, the suffragette Emily Wilding Davison died in tragic circumstances. Four days previously she was at the Epsom Derby, standing by the white rail near Tattenham Corner. A member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the most notorious of the groupings campaigning for the parliamentary vote for women, the tall, slender, athletic, forty-year-old Davison, wore no visible sign that she was a suffragette. However, concealed from the crowds, she had pinned to the lining of her jacket two flags in the WSPU’s colours of purple (which represented dignity), white (purity) and green (hope). As a small group of horses galloped past her, she dashed under the railing, raised her hands and tried to grab the reins of the King’s horse, Anmer. With great force, Anmer knocked her over, rolled on his back, kicking her furiously. Davison suffered a fractured skull, severe concussion and internal injuries. She was taken to Epsom Cottage Hospital and operated on but never recovered. Her death was not only reported in all the main British newspapers of the day but captured on Pathe news and relayed around the world, a moment in British political history that has become fixed in time.

The coroner returned a verdict of ‘accidental death’. Davison probably did not intend to commit suicide. After all, found on her person at the hospital were a helpers pass for a Suffragette Summer festival to be held the evening of the 4th June at Empress Rooms, High Street Kensington as well as some envelopes and writing paper indicating, perhaps, that she expected to be arrested and would be writing to friends. Also in her pocket was a purse containing a return ticket from Epsom Race Course to Victoria Station, London. It was once argued that the very existence of this ticket was proof that Davison intended to travel back home and had not planned to take her life. But further research has revealed that the popularity of the Derby at this time was such that an excursion return ticket was all that could be bought. A recent TV programme titled Clare Balding’s Secrets of a Suffragette, screened on Channel 4 in May 2013, carefully examined a lot of evidence about Davison’s death, even engaging in a forensic analysis of the film footage. It came to no firm conclusion that she did or did not plan to commit suicide.

So why did Emily Wilding Davison commit such a dangerous act that lead to her death? It is important to remember that women in Britain in 1913, by virtue of their sex, were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. This ruling applied to women of all social classes and occupations – duchesses, schoolteachers, housewives, domestic servants. It was this exclusion from a basic human right in a society that claimed to be a ‘democracy’ that fired the activism of the suffragettes of the WSPU, including Davison.

Davison joined the WSPU in November 1906. Undoubtedly her frustration at the secondary status of women in Edwardian society fuelled her growing interest in the women’s movement. Although born into a comfortable middle-class home, the death of her father, when she was nineteen, left her mother in straitened circumstances. The bright, bookish Davison, studying at Holloway College, had to abandon her studies. However, she was determined not to waste her academic talents and took a job, thus enabling her to save enough to pay for a term at St. Hugh’s Hall, a women’s college recently founded in Oxford. Although she passed her Oxford University examinations with first class honours in English Language and Literature she was unable to be awarded her degree since, at that time, only men at Oxford were granted such an honour. Undaunted, the determined Davison then entered London University, which did award degrees to women on equal terms with men, graduating from there with honours in classics and mathematics. Yet despite these qualifications, Davison found that the range of jobs she could enter was severely restricted. Typically for university educated women of her day she became a schoolteacher and, when that was not too successful, went back to being a resident governess.

In 1909 Davison gave up her employment in order to focus full time on her suffrage work, thus facing financial insecurity for the rest of her life. A feminist and a socialist she had, claimed the journalist Rebecca West, a ‘moral passion’ to end injustices against the disadvantaged. Certainly, over the next four years, the lively Davison embarked on some of the most daring of exploits in order to highlight the importance of the women’s suffrage campaign.

She was imprisoned eight times, went on hunger strike seven times, and was forcibly fed forty-nine times. She was so haunted by the horror of her first feeding in the autumn of 1909 and the cries of her comrades as they, too, underwent the procedure that she came to believe that only through the giving of a life would the British government be forced to stop this hideous torture of women who were campaigning in a just, democratic cause. On at least three separate occasions, while in prison in 1912, she threw herself over the railings. But she did not die, despite her injuries. Nor did the prison authorities stop forcibly feeding hunger-striking suffragettes.

Recuperating at her mother’s home in Longhorsley, near Morpeth in Northumberland in early 1913, the hard-up Davison was looking for work. Votes for women had still not been won. Indeed, the WSPU now largely operated as an underground movement since it was increasingly adopting illegal, violent tactics although non-violent, legal forms of protest were still evident, such as protests in churches about the treatment of the much loved WSPU leader, Emmeline Pankhurst. It was widely feared that Mrs Pankhurst, who was continually out of prison under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, was being slowly killed by a ruthless, undemocratic government. It was under these circumstances that the unpredictable Emily Wilding Davison undertook her final act. She was a risk taker who knew that her action, in the cause of democracy, might have fatal consequences.

Five years after Davison died, certain categories of women aged 30 and over were given the parliamentary vote thus bringing over 8 million women onto the electoral roll. Women had to wait until 1928 to be granted the parliamentary franchise on equal terms with men, at the age of 21.

Equality for women was at the heart of the suffragette struggle – and is still an issue of contemporary relevance. The right to the parliamentary vote is still denied women in some countries, such as Saudi Arabia, while women are still under-represented in most areas of public life, even in ‘democratic’ Britain. A reshuffle of ministerial posts by our Coalition Government on 7 October 2013 saw the number of women creeping up from just 23 to 25, or 20% of the 125 jobs available. Prostitution, sex trafficking and violence against women, which the suffragettes emphasised exploited women, have still not been eradicated. And a substantial pay gap between the earnings of women and men still exists. Many of the issues so dear to Emily Wilding Davison are still of relevance, 100 years after her death.

Note: This post represents the views of the author, not those of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink for this post: https://buff.ly/19qNPiI.

June Purvis is Emeritus Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Portsmouth.

June Purvis is Emeritus Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Portsmouth.

This post is part of Democratic Audit’s Gender and Democracy series, which examines the different ways in which men and women experience democracy in the UK and explores how to achieve greater equality. To read more posts in this series click here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.