Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement

The UK Parliament and its counterparts across the globe are increasingly connecting with citizens through social media. Cristina Leston-Bandeira gives an overview of a new study into the Twitter and Facebook strategies of national parliaments. She finds that in the UK, 80% of Parliament’s social media postings tend to be used to report parliamentary activity rather than to carry out genuine engagement, although the Scottish Parliament is much more deliberative.

Over 26,000 people follow the House of Commons on Twitter. Source: Twitter/UK Parliament

One year after the Inter-Parliamentary Union approved unanimously a resolution on using social media to enhance public engagement and as the parliament of one of the most battered European democracies, Italy, introduces its Twitter account, we ask: to what extent are parliaments using social media? And are social media promoting new forms of parliamentary engagement?

In an era of rapidly declining levels of trust, parliaments have come to portray the face and cause of political disengagement. As a reaction to this, parliaments all over the world have turned to public engagement. Over the last decade, parliament’s role of public engagement has developed to such a point that in some parliaments it sits side-by-side with parliaments’ traditional roles of legislation, scrutiny and representation. New departments have been created, new services developed, programmes expanded.

For a long time parliaments were institutions representing the public, but without the need to actively communicate with this same public. This has changed dramatically over the last decade – although still with considerable variation. In this context, the use of social media opens up new opportunities for parliaments: a direct access to citizens not mediated by the media or parties, more direct access to a younger public, the possibility to react more quickly to news and events, the possibility to engage the public into a conversation and the possibility to target more specific issues.

And yet, parliaments have been slow in adopting social media. This is partly due to the nature of parliamentary institutions, which makes them very poor bedfellows to technology. The pace of technological change simply does not suit parliamentary decision-making. Likewise, social media are not necessarily suited for institutional engagement. Social media imply an individual voice that parliament does not have. Parliament is constituted by a collective of many actors and it is not the politician who speaks for parliament, it is the parliamentary official, who needs to be at all points non-biased.

The value of social media, however, lies in its ability to facilitate connections through quick, spontaneous, and informal reactions; social media imply a persona behind its input. The use of social media raises therefore a number of challenges to parliaments and, to a large extent, requires these institutions to engage in a new style of communication beyond the traditional institutional one. It also requires resources. Those parliaments most successful in maintaining a social media presence are those that have invested considerably in this area, often having a team specifically dedicated to the management of these accounts.

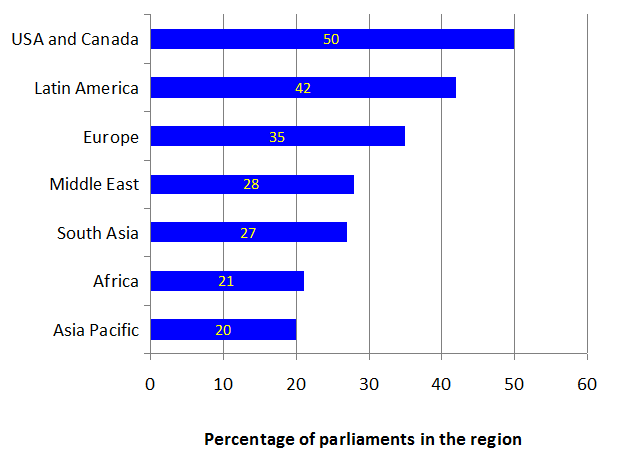

Still, increasingly, parliaments need to be seen to at least engage with this tool. Since 2008, parliaments have started to open Facebook and Twitter accounts as extra channels of communication with the public. Our research shows that, as of June 2013, 29% of national parliaments all over the world had a Facebook and/or Twitter account, with Latin America clearly overtaking Europe as seen in Figure 1. Latin America is also where we find some of the most innovative and embedded use of digital means to integrate citizens into parliamentary business. See, for instance, the Brazilian e-Cidadania and e-Democracia, or the Chilean Virtual Senator.

Figure 1 – Proportion of parliaments with a Facebook and/or Twitter account, per continent

This adoption varies very considerably in its use. We found that in Europe, the vast majority of parliamentary Facebook and/or Twitter accounts had less than 100 users per 100.000 people, with 70% of the Facebook accounts having less than 10 users per 100.000. Likewise, usage varies very considerably, with most reproducing traditional institutional forms of communication: reporting and announcing business taking place in parliament, rather than necessarily engaging the public.

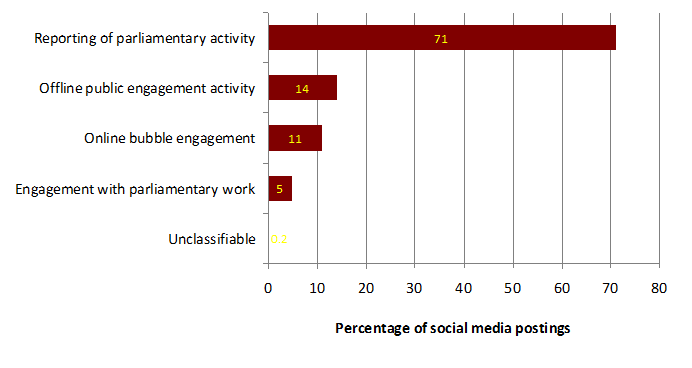

To test this, we developed a contents analysis of 3007 postings of institutional Facebook and Twitter accounts over a period of four months, between 1/11/2011 and 20/2/2012 of six European chambers – European Parliament, French National Assembly, French Senate, Scottish Parliament, UK House of Commons and UK House of Lords. We found that 71% of this activity aimed to simply report on parliamentary business – with 44% referring merely to timetabling issues. Figure 2 shows that about 29% of the postings related to engagement, with only 5% referring to actual engagement with on-going parliamentary activity. Instances inviting responses to an enquiry, for example, petitions, or other instances where the aim of the posting is to encourage engagement that could lead to actual participation. The rest of the engagement postings refer to pure engagement activities, focused usually on a cultural, historical or educational dimension; 11% of the postings referred to engagement taking place within the online bubble with no other output than an online conversation and 14% related to actual engagement activities taking place in parliament.

Figure 2 – Contents of parliaments’ social media postings (n=3007 postings)

Our analysis also showed important differences between the chambers included in our sample. Whilst the French National Assembly and the UK chambers’ social media accounts aimed mainly to report on parliamentary activity (over 80% of their postings), the other three chambers had a much higher proportion of postings focused on engagement. To note in particular the Scottish Parliament, where the majority of the postings (52%) focused on engagement.

Parliaments are still very new to social media. Whilst it is still unclear what sort of impact these tools can have on public engagement, legislatures are increasingly expected to have a social media presence. This requires however a new style of communication and additional resources. Our contents analysis shows that social media is still being used mainly according to traditional forms of communication. But our sample is now two years old and recent activity indicates continuing innovation in this area, with for instance the House of Commons’ Select Committees playing a more active role in using these tools to engage with the public. Also, our analysis focuses on institutional accounts.

It is actually very difficult for an institution to establish a conversation on social media – utilizing social media for public engagement requires a voice. A more effective way of finding that voice may be through facilitating access to a multiplicity of more specific social media accounts.

—

This blog post derives from an article published in Information Polity: C. Leston-Bandeira and D. Bender, ‘How Deeply are Parliaments Engaging in Social Media’, Information Polity, 18 (4), 2013, pp. 281-297. A near to final version of this article is available through open access here.

Note: This post represents the views of the author, and does not give the position of the LSE or Democratic Audit. Please read or comments policy before voting. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1ffu6tc

—

Cristina Leston-Bandeira is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Hull. She works on comparative legislatures, focusing in particular on the relationship between parliament and citizens. This has led her recently to focus on public engagement, parliamentary reform and the impact of the internet on parliament. She currently holds an ESRC grant for a study on how parliaments manage the image they portray on their websites, and edited the books Parliaments and Citizens (Routledge, 2013) and Southern European Parliaments in Democracy (Frank Cass, 2004)

Cristina Leston-Bandeira is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Hull. She works on comparative legislatures, focusing in particular on the relationship between parliament and citizens. This has led her recently to focus on public engagement, parliamentary reform and the impact of the internet on parliament. She currently holds an ESRC grant for a study on how parliaments manage the image they portray on their websites, and edited the books Parliaments and Citizens (Routledge, 2013) and Southern European Parliaments in Democracy (Frank Cass, 2004)

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How do parliaments use #SocialMedia? Here is an interesting article about it https://t.co/ESCQhWGv1A

“@Discue: How parliaments use #SocialMedia? An interesting article about it https://t.co/aVo2KFnWNp” @HouseofCommons has lots to learn

Now really? “Parliament: Social media for broadcast,not engagement says new study” https://t.co/FsmtBm0c06”

RT @demsoc: Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement: @estrangeirada https://t.co/1WuVFUOClm

Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement : @estrangeirada https://t.co/1uh9FISc3T

Parliament: Social media for broadcast,not engagement says new study. https://t.co/4wPcePPYnp

RT @estrangeirada: The @ScotParl, one of most effective parliaments using social media for engagement, & @Europarl_EN: https://t.co/KsssxyEX…

Parliaments and social media – reporting not engaging? @democraticaudit blog by @estrangeirada https://t.co/LDUbtoZvQF

Interesting post by @estrangeirada on parliaments’ SM use https://t.co/j2E4qTv11c Links up w/ my @democraticaudit post https://t.co/ltR74gJ3rD

Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement … when will we have… https://t.co/bUn0Gfg8Cp

Neat post by @estrangeirada on how UK Parliament uses social media mainly to report, not engage; via @democraticaudit https://t.co/zhHwVienrv

RT @demsoc: Noted: https://t.co/rrOognOMZd

Surprise! Parliaments use soc media as reporting tool insted of 4public engagement. Web2 is no panacea for democracy https://t.co/05Q8yGpnnB

Is there analysis of how prov. legislatures use social media? Could emulate this study of natl parliaments https://t.co/0CubZV4GCF cc….

Parliaments use social media mainly for reporting, rather than engagement. My take for @democraticaudit blog: https://t.co/KsssxyEXUj

29% of world’s natl parliaments have a twitter/facebook acct, but #cdnpoli House of Commons MIA (only @SenateCA) https://t.co/ZvZFCrnITp 1/2

#highfive @scotparl > @democraticaudit 52% of tweets by Scottish Parliament are aimed at genuine public engagement https://t.co/dQ0q8qbS1o

52% of tweets by Scottish Parliament are aimed at genuine public engagement https://t.co/nP9Ywlc7i9

How do the world’s parliaments use #socialmedia? https://t.co/RaigKQXubF via @democraticaudit #ComPol

Parliaments still use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/KkAcquYm2Q @paredespablo

Parliaments still use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/Nvzt2S5cDH

RT @PJDunleavy Parliaments use social media as reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/e3SsKOmQpO via @democraticaudit

In UK, 80% of posts=push

Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/HGS8vH0Ptw

New on DA: Cristina Leston-Bandeira of @uniofhull – international comparison of how parliaments use social media https://t.co/asGUVTjl1q

@JennyBloomfield Did you see this? @ScotParl leads the way in using social media for genuine conversations: https://t.co/jfzsF24rYm

80% of UK Parliament social media use is transmission, not genuine engagement – interesting work by @democraticaudit https://t.co/jfzsF24rYm

80% of tweets by UK Parliament are reporting news of parliamentary activity https://t.co/Jk1lgeI4CS – @estrangeirada on Democratic Audit

Some don’t use it at all! #SaborHr // Parliaments use social media as a reporting tool… https://t.co/4BFXfANi6N via @democraticaudit

Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/Nvzt2S5cDH

Great blog by @estrangeirada: Parliaments use social media mostly for reporting, not engagement https://t.co/AxqordXbil via @democraticaudit

Parliaments use social media mainly as a reporting tool rather than for public engagement https://t.co/WjH3XDCdS6