Allow young people to set the political agenda by giving youth parliaments the power to call referendums

In the latest post from our series on youth participation, Gerry Stoker challenges the idea that the innocence and political inexperience of young people is a problem we need to solve. Instead, he argues that young people have a less fixed view of politics and are more willing to believe it could be better. He makes a proposal to put real policy-making people into the hands of young people by giving their elected representatives the right to call referendums on issues of their choosing.

A debate at the UK Youth Parliament: should the institution have more powers? Credit: UK Parliament, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In their role as citizens, young people bring a certain innocence to the proceedings that for the sake of our democracy we should seek to work with. Rather than despairing about the relative non-engagement of young citizens in formal politics, we should be pleased that their relative divorce from politics has limited their negative experience of it. Cynicism and fatalism about the awfulness of politics is more prevalent among older citizens as decades of negative media, broken promises, expenses and lobbying scandals, and other political failings have taken their toll. The inevitable inexperience of young citizens also brings another advantage: they are more open to the prospects for change and doing things differently. A different political offer – one that opens up decisions to a wider set of influences – could draw in younger people to a greater degree because of their less fixed view of politics and their willingness to believe it could be better.

Inexperience offers potential

In current policy thinking the inexperience of young citizens is often seen as a problem to be fixed. Younger citizens are sometimes seen as naive and in need of a dose of reality. Michael White, the longstanding political correspondent of The Guardian captured this sentiment: ‘Only 46% of 18-to24-year olds actually vote, many saying it makes no difference. Yet they are the same people who complain that oldies (76 per cent of whom do vote) are treated better than the young. How about a new word: “Kidiots”’. The implication of this argument is that young people need to wake up and recognise that engagement with politics, for all its faults, is the only way they can protect their interests.

A softer line towards the inexperience of youth–the one most prevalent in the Youth Citizenship Commission and many other reports– is that younger people need to be enabled to become citizens. As the Citizenship Foundation website puts it: ‘Citizenship education is essential for preparing our young people for our shared democratic life’. Young citizens need an active programme of citizenship education, opportunities to engage, and then they will grow into full citizenship, knowing their rights, valuing democratic decision-making and recognising the complexity of political decision-making.

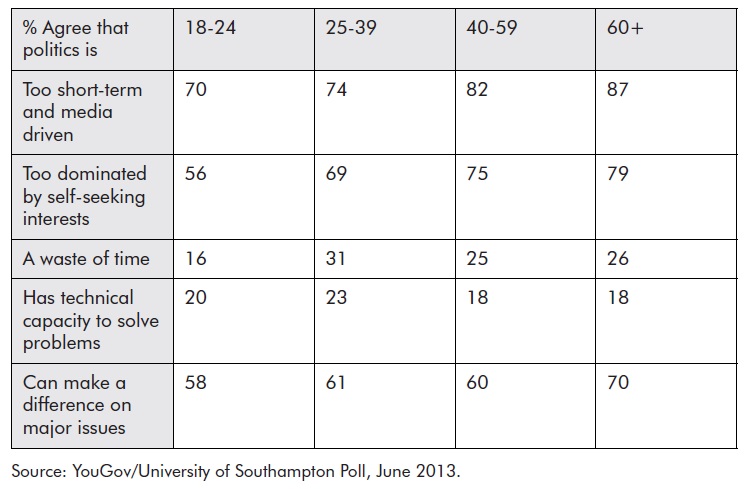

But what if increased experience of politics as practiced in today’s contemporary democracies actually tends to make you more negative about the political system? The evidence points in that direction. Disenchantment with politics is greater among older citizens than younger citizens. In June 2013 a University of Southampton/YouGov poll asked a representative sample of British citizens about the capacities and limitations of politics to meet today’s social and economic challenges. As Table 1 shows, negative responses about the failings of the political system were more prominent among older citizens. That is not to suggest that younger citizens were giving glowing reports about politics but they were less negative than others. Across almost every measure, older citizens hold more negative attitudes about the capabilities and intentions of politicians. Yet belief that government can make a difference is slightly stronger among these groups. Disappointment is, perhaps, the inevitable product of belief that politics and government can make a difference but is failing to do so.

A December 2013 poll by ICM/ The Guardianshows a similar pattern of differences between citizens based on age; indicating that negativity towards politics becomes concentrated with age. Whereas anger towards politics and politicians was identified as their most instinctive response by over half of all citizens above 45 years old, among citizens aged between 18-24 anger was chosen by only a third. Admittedly a third of the youngest citizen group chose boredom as their main reaction to politics, although 5 per cent said they were inspired by it, compared to 0 per cent of those aged 65 and over. Younger citizens shared many of the same issues as other citizens when it came to identifying what puts them off voting. Many, like other citizens, feel that politicians are on the fiddle, that parties do not represent their mix of views or are too similar. The top concern for all citizens was the failure of politicians to keep their promises. Yet on that point younger citizens were more forgiving with 59 per cent of those aged 18-24 picking that concern compared to higher proportion in all older age groups, reaching the high point of 70 per cent of those citizens aged 45-54.

Table 1: Negativity towards politics and age

Younger citizens are more willing to change

So the evidence suggests that engagement with politics tends to make you more negative about it. Am I then moved to back the suggestion of UK comedian Russell Brand that politics is so bad that the only thing to do, if you are young, is stay away from it? That Brand has captured one part of the concerns of many young (and not so young) citizens is clear. But what he fails to recognise is that many would welcome a shift to a more effective and dynamic democracy rather than his vacuous concept of revolution. In short, there is evidence that if the politics on offer got better, or perhaps worse, many citizens, but younger citizens in particular, would shift to become more positively engaged.

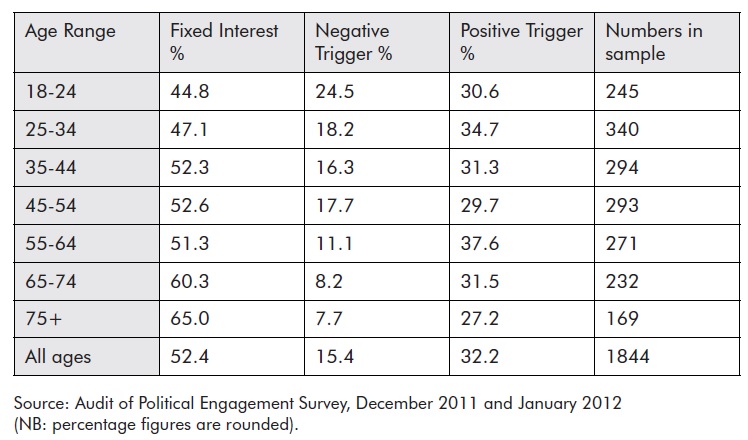

There are good reasons for thinking that citizens might not be fixed in their interest in politics. After all in many parts of our lives what we do and how we react is dependent on context and circumstances. Testing this prospect in terms of politics through survey work undertaken with the Hansard Society in 2011/12 we found (as reported in Table 2) that about half of citizens would shift to greater interest in politics given the right trigger and that the younger citizens rather than older ones could be drawn into politics to a greater degree if the context for engagement changed.

We used survey responses to negative and positive triggers to see their effects on people’s level of interest. The negative trigger is based on the idea that many people do not really want to engage that much, but if politics becomes really bad, in terms of the self-serving behaviour from politicians and powerful interests , more citizens would get themselves involved.

Table 2: Interest in politics by age and triggers

Another line of argument sees it differently, arguing that what is needed to get citizens involved is a positive trigger, a sense that politics could be better, less rigged and where the views of citizens might come to matter in a way that they do not now. In those circumstances people would be more willing to lend their interest and voice to political proceedings.

For the population as a whole, we found that just over half were fixed in their preferences. But that of course means half of citizens could be persuaded to shift to greater interest in politics. For those that changed their response, the positive trigger proved twice as powerful as the negative trigger in stimulating a change of interest. Younger citizens are less fixed in their pattern of interest and as a result more likely than older age groups to be triggered into greater political action.

A chance to set the political agenda

So in the light of the evidence and analysis presented above, I support a policy proposal that builds on the proposal of others to give the vote in all elections to citizens from 16 years-old onwards. Not only should we give young people the vote but we should give them more control over the agenda of politics. My proposal is to give the UK Youth Parliament, the Northern Ireland Youth Forum, the Scottish Youth Parliament and the Children and Young People’s Assembly for Wales the right to call a people’s ballot or citizens’ initiative referendum on a topic of their choosing. How they come to select the one topic for any one year would be down to them. The formation of the specific question could be subject to approval by the Electoral Commission. The question would be posed to voters at the same time as when other elections are being held. In years of the local elections the ballot would be advisory but would give a powerful message. In EU Parliament and General Election votes the ballot would be decisive on the grounds that all voters would be entitled to a say.

The rationale is to make a shift in the kind of politics on offer and so build on the innocence of youth. Young citizens might just have, in enough numbers, the desire, the imagination, and the lack of cynicism to challenge the way in which politics is done in contemporary democracies such as the United Kingdom. Backed by a reinvigorated programme of citizenship education, ‘oldies’ – such as myself –might be able to ride on the coat tails of the young towards a better democratic politics.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the author and does not give the position of Democratic or LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1nKc1Za

—

Gerry Stoker is Professor of Politics and Governance at the University of Southampton. He was the founding chair of the New Local Government Network think-tank, and his book Why Politics Matters won the 2006 political book of the year award from the Political Studies Association. He has provided advice to various parts of UK government and is also an expert advisor to the Council of Europe on local government and participation issues.

Gerry Stoker is Professor of Politics and Governance at the University of Southampton. He was the founding chair of the New Local Government Network think-tank, and his book Why Politics Matters won the 2006 political book of the year award from the Political Studies Association. He has provided advice to various parts of UK government and is also an expert advisor to the Council of Europe on local government and participation issues.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] In the latest post from our series on youth participation, Gerry Stoker challenges the idea that the innocence and political inexperience of young people is a problem we need to solve. Instead, he … […]

Youth participation in politics, and the rights of Youth Parliaments https://t.co/eQV1Um3u9c #youngvoters

Do you think @UKYP should be able to call a referendum based on young ppl’s views? Gerry Stoker does – read this: https://t.co/sOuDN3n6cn

Young citizens might just have the desire, imagination, & lack of cynicism to challenge how politics is done https://t.co/QYeghwwUvt

Gerry Stoker:Allow young people to set the political agenda by giving youth parliaments the power to call referendums https://t.co/wpVIHq2YFt

Interesting findings. Why is it, then, that the young are generally less likely to vote? (I’m not questioning the findings, because various possible explanations suggest themselves, but I wonder what may explain this.)

I’m not so sure about the positive proposal though. Partly, I’m not sure I’d welcome the rise in referenda, but also I wonder how effective a measure it is – the young can put whatever they like on the agenda, but the old can simply vote it down. If they can persuade enough of the old to back it in a referendum, then why can’t they get it on the agenda in the first place?

Allow young people to set the political agenda by giving youth parliaments the power to call referendums https://t.co/aPctKNUO3t