Recent Nigerian experience illustrates the importance of ensuring that the institutional, financial, and operational powers of election management bodies are safeguarded

How should countries organise their systems of electoral administration? Recent election cycles in Nigeria illustrate the importance of ensuring that electoral management bodies are not just institutionally independent, but that steps are also taken to ensure that sufficient emphasis is placed on the institutional, financial, and operational powers and functions of these organisations, argues Ibrahim Sani.

Left: Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan (Credit: Blog do Planalto, CC BY ND 2.0)

Elections are complex political processes, requiring impartial electoral management bodies (EMBs). Democracies around the world encounter various challenges of electoral quality. There is the abuse of postal voting in the 2004 Birmingham local elections, voters’ frustration in the 2010 UK general elections and the contentious vote recount of the US 2000 presidential elections. Also, there was the use of bloated voter register in 1992 Ghanaian election as the 2007 April elections in Nigeria. This questions the assumption that permanent and professional EMBs will conduct credible elections. Moreover, electoral umpires have existed, but were not allowed to perform effectively and achieve democratic visions, making it imperative to inspect the bureaucratic fundamentals of EMBs. The purpose is to clarify the potential effects of institutional independence of EMBs in guaranteeing electoral credibility.

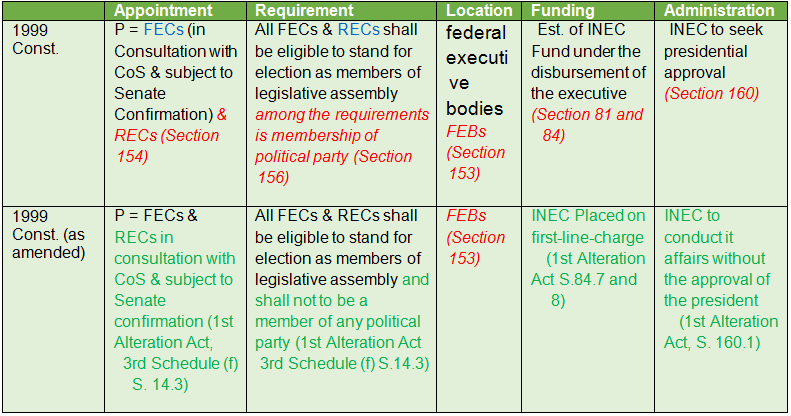

One way to illustrate this is by focusing on the constitutional authority provided to the electoral commissions. Whilst constitutionally institutionalised, the powers of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) in Nigeria appear constrained in many ways. Table I below indicates the President as the most influential person in the appointment of all 12 federal electoral commissioners (FECs), 37 residential electoral commissioners (RECs) and the chief electoral commissioners. Although the President is to consult the Council of State (CoS) and seek legislative approval, he alone appoints all the RECs who are the strategic field-agents of the commission at the 36 federating units, plus the capital. In addition, he is at liberty to appoint party loyalists and has the commission within his reach. After all, agencies listed here are answerable and receive their funds from an executive disbursement.

Table 1: Comparative Autonomy of INEC Nigeria in 2007 & 2011 elections

These arrangements affect the commission’s institutional autonomy and its credibility in the conduct of the 2007 elections. For example, it is seen as the most significant institutional problem facing INEC which the country failed to rectify during the 2006 Amendment Act. People feared that individuals appointed by the President could dance to his tunes and do his biddings. Experiences before, during, and after the elections seem to confirm this fear as there were reported cases of electoral frauds, irregularities, shortage of electoral materials, ballot box stuffing, an announcement of fake and unaccounted election results, and an alleged revelation of how politicians do conspire with electoral officials to create electoral windfall.

Consequently, the legitimacy of the elections was doubted to the extent that the 2007 elections were adjudged the worst in Nigeria’s post-independence electoral history. Indeed, the beneficiary of the elections acknowledged its shortcomings, as did majority of Nigerians. A blogger described the elections as a reflection of near-total dominance of the PDP and pervasive influence of the outgoing president– a position acknowledged by INEC when it blamed the central bank and due process office for much of the 2007 electoral failures.

However, in the build-up to the 2011 elections certain amendments (indicated in green Tab. I) like subjecting the appointment of RECs to legislature scrutiny raise the impartiality of the commission. Also, the removal of party membership as requirement for appointment has enhanced its non-partisanship. For example, it is believed that INEC in the 2011 elections has expanded and improved the political environment for better participation and competition. It has elevated electoral fairness by providing fair grounds for democratic engagement. The 2011 elections have conformed to democratic values expressed by the African Union and ECOWAS.

Other significant variables toward these successes are the financial and administrative powers which the commission enjoyed. It is reported that INEC independently designed and executed the elections, facing all the challenges squarely. Election observers – domestic and foreign – commended the commission’s preparedness, applauded the systematic deployment of electoral officials, and uphold the 2011 elections. For example, INEC procured 232, 000 DDC machines, cameras, and printers and had them delivered as early as 29th November 2010; recruited and trained 368, 812 NYSC as presiding officers; purchased 9000 units of 6.5 KVA generating sets as standby in case of battery failures and 150, 000 collapsible ballot boxes and made operational and functional during the presidential, gubernatorial and other elections 119, 973 polling units, using enough and qualified hands.

In conclusion, as Nigeria is approaching yet another round of general elections, there is the need for the legislative houses to place more emphasis in ensuring that the commissions’ institutional, financial, and operational powers and functions are protected in order to safeguard the sanctity of the ballot. To other countries, this piece points that whatever model of EMBs in operation, there is the need for policy practitioners and public activists to ensure that all is done towards a hitch-free elections.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Ibrahim Sani is a PhD student in Politics, School of Political and Social Science, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He is working on a thesis entitled ‘Electoral Governance: Understanding the Democratic Quality of Elections in Nigeria’. He had his M.Sc. and B.Sc. degrees from Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Nigeria. After his first degree, he served as Electoral Officer in Funtua Local Government, Katsina State, Nigeria and as Administrative Officer, with National Poverty Eradication Commission, Abuja, Nigeria. Later after his master’s degree, he joined Usmanu University as lecturer II in Political Science.

Ibrahim Sani is a PhD student in Politics, School of Political and Social Science, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He is working on a thesis entitled ‘Electoral Governance: Understanding the Democratic Quality of Elections in Nigeria’. He had his M.Sc. and B.Sc. degrees from Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Nigeria. After his first degree, he served as Electoral Officer in Funtua Local Government, Katsina State, Nigeria and as Administrative Officer, with National Poverty Eradication Commission, Abuja, Nigeria. Later after his master’s degree, he joined Usmanu University as lecturer II in Political Science.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Recent Nigerian experience illustrates the importance of ensuring that the institutional, financial,…. […]

What can we learn from the role of Election Management Bodies in recent Nigerian elections? https://t.co/cYfsTnuw2S

Recent Nigerian experience shows it’s vital to safeguard the powers of election management bodies https://t.co/TuIK790V4m

RT @democraticaudit: What do recent elections in Nigeria tell us about how to configure election management bodies? https://t.co/ypGzznA0Au

Recent Nigerian experience illustrates the importance of ensuring that the institutional, financial, and… https://t.co/CZ6bXksybP