“Arrogant Posh Boys?” The Social Composition of the Parliamentary Conservative Party

Since assuming the leadership of the Conservatives, David Cameron and his inner circle have been dogged by questions about their priviliged background. This has only served to intensify broader issues which the Conservative party has long been seen to suffer with in matters of diversity and equality. It was to address these issues that Cameron introduced a ‘Priority’ or ‘A’ list of 200 exceptional candidates, half of whom were women. Michael Hill explains the effect which this approach had on the social composition of the parliamentary conservative party, as well as the broader difficulties likely to be faced by the party in respect of these issues.

In October 2012 the Conservative Party Chief Whip Andrew Mitchell was forced to resign, after he was accused of calling Downing Street police officers ‘plebs’. The accusation, fiercely denied by Mitchell, drew attention to the privileged social background of many Conservative parliamentarians, especially as Conservative backbencher Nadine Dorries had previously attacked David Cameron and George Osbourne for being ‘two arrogant posh boys who don’t know the price of milk.’

Cameron, the first Old Etonian to lead the party since Sir Alec Douglas Home in 1964 was elected Conservative leader in 2005, on a platform of ideological and organisational modernisation. These organisational reforms were aimed at addressing the party’s narrow social background and making the party more representative of modern Britain by recruiting more female and ethnic minority Conservative MPs. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party was the first British political party to be led by a woman, who went on to become the country’s first and to date only female prime minister, the party has had a poor record of producing female MPs: prior to the 2010 election the highest number of female Conservative MPs was twenty, (out of a total of 336) elected in 1992. In the post war period the party has consistently selected fewer female candidates than Labour. Moreover, the last time the Conservatives selected more female candidates than the Liberal Democrats (and their predecessors) was 1970. Furthermore, there appeared to be a culture of overt sexism within the party and a preference amongst older activists (male and female) for candidates to be married, white, male professionals. However, the Conservative’s record on recruiting ethnic minority MPs is even worse. The party had no ethnic minority MPs between 1997 and 2005, only fourteen candidates at the 2001 election were black or Asian and of these only two were in winnable seats. There is evidence of racism within the party and that good prospective candidates have been passed over, simply on account of their ethnic background.

Despite these clear failings the party was unwilling to use a quota system, similar to Labour’s all-women shortlists, for ideological reasons. Instead Cameron’s solution was to introduce in 2006, a ‘Priority’ or ‘A’ list of 200 exceptional candidates, half of whom were women. Constituency parties in target seats and those with retiring MPs had to choose candidates from the list. The list also included a significant number of ethnic minority and disabled candidates. However, even these limited proposals met with fierce opposition from many traditional Conservatives, who believed that candidates should be selected purely on merit. There were also accusations that popular local councillors and campaigners were being blocked in favour of ‘celebrities and beautiful people’ such as Adam Rickitt and Louise Bagshawe (later Mensch). Consequently, in 2007 a compromise was agreed in which local associations could choose from the entire candidates’ list as long as at least half the interviewees were women, marking the effective abandonment of the ‘A’ list.

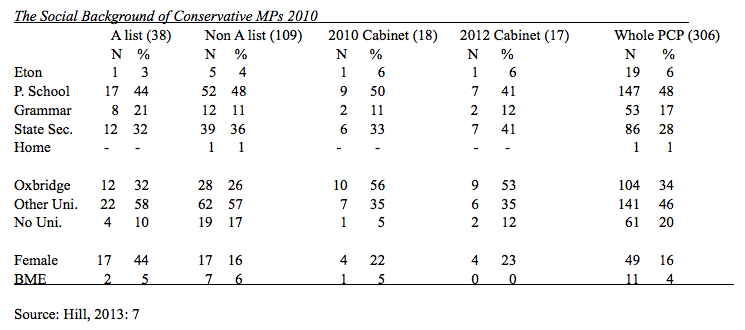

What effect did the ‘A’ list have upon the social composition of the PCP? Of the 306 Conservative MPs elected in 2010, 147 were non-incumbents, of whom 38 had been selected from the ‘A’ list. The clear beneficiaries were female candidates, (see table below) 17 female ‘A’ listers were elected (45%), compared with 17 women elected out of the 109 new MPs who were not on the ‘A’ list (16%). However, in the areas of race and class, the ‘A’ list made little difference Moreover, it will take several years before the ‘A’ list has an effect on the social composition of the Conservative cabinet ministers, who are the most well known members of the PCP: public school and Oxbridge MPs continue to dominate (see table). Almost a quarter of the cabinet are women, but there are no ethnic minority cabinet ministers.

However, it may be the case that in the long run the social composition of the parliamentary party does not matter. The Conservative dominance between 1979 and 1992 was achieved despite the public school and Old Etonian cohorts within the PCP being much higher than they are today. However, at the time the party was led first by Margaret Thatcher and latterly John Major, both of whom came from relatively humble backgrounds. Perhaps the Conservative’s most pressing problem with respect to social composition is not the parliamentary party as a whole or even the cabinet. Rather it is that their two most prominent figures, Cameron and Osbourne are both millionaires from upper class families: Cameron went to Eton, whilst Osbourne is the heir to a baronetcy. Even this would not necessarily matter were it not for the difficult economic climate and the perception that ordinary people have to bare a heavier burden than the wealthy due to the government’s economic austerity measures. It may then be the case that the Conservative Party can do nothing about their ‘arrogant posh boys’ image and simply have to hope that the economy improves and renders it electorally unimportant.

This post is based on an article in Political Quarterly.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit, nor the British Politics and Policy blog, on which it was originally posted, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr. Michael Hill is an expert in British Politics and has taught at the Universities of Huddersfield and Central Lancashire. His work on Conservative Party leadership has been published in Political Quarterly, Politics, British Politics and Political Studies Review.

Dr. Michael Hill is an expert in British Politics and has taught at the Universities of Huddersfield and Central Lancashire. His work on Conservative Party leadership has been published in Political Quarterly, Politics, British Politics and Political Studies Review.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.