Constant government reshuffles are bad for policy, government, and accountability

Ministerial reshuffles are part and parcel of British government. While prime ministers often find them attractive, David Cameron has resisted the temptation to chop and change too much, making a virtue out of stability but occasionally being criticised for his loyalty to underperforming or scandal-hit ministers. The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee has recommended that cabinet ministers should remain in their post for the length of a parliament. Democratic Audit’s Sean Kippin examines whether this, and the Committee’s other proposals, could actually work.

As Prime Minister, David Cameron has largely resisted the temptation to chop and change his top team. In just over three years, he has engaged in a single major reshuffle, and in doing so left 11 positions – including each of the ‘great offices of state’ – untouched. This is in stark contrast to his two immediate predecessors, who were comparatively trigger-happy in showing the door to Ministers whose faces, for one reason or another, ceased to fit.

10 Downing Street (Credit: Leonard Bentley, cc by SA 2.0)

10 Downing Street (Credit: Leonard Bentley, cc by SA 2.0)

An influential committee in the House of Commons has said that Cabinet Ministers, particularly, should stay in post for the full term of a Parliament, with Junior Ministers serving for an assumed minimum of two. But is this realistic? It is easy to see that this line of thinking might be optimistic, with the political pressures to promote the next generation, reward good performance, and prevent the emergence of rival power-bases being too great to resist.

In choosing who to move, and who to keep, a Prime Minister has a number of considerations weighing against one another; be they based on ideological or other reasons. Impressive junior Ministers and Parliamentary Private Secretaries may have earned a promotion, while older Cabinet Ministers may be reaching the end of their political life. Meanwhile, younger backbenchers may be seen to have earned an opportunity at high office. All of this creates substantial pressure for Cabinet personnel change.

In a Coalition, the Prime Minister has less leeway over the makeup of his or her Cabinet, with appointments generally decided at the outset of the government’s time in office, and only altered in case of resignation, scandal or death. This, at least, is the way that Coalitions in Western Europe tend to operate. With recent structural changes underway in this country, and Coalition threatening to become the norm, the Committee could well get its wish.

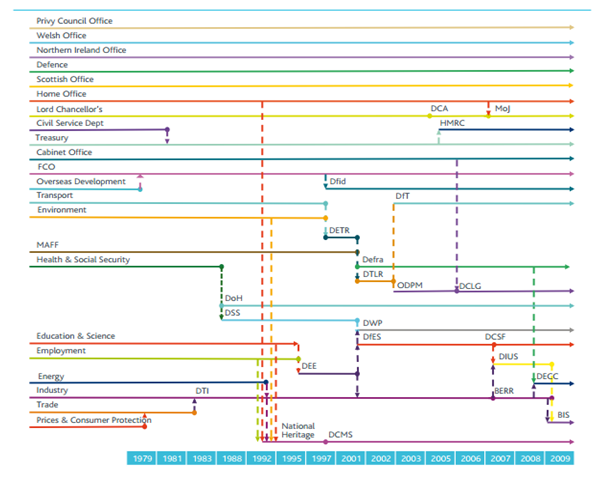

Whitehall reorganisations also trigger demand for reshuffles. In recent years we have seen a number of instances of Departments being merged, abolished, split up, or newly created to better reflect the priorities of the Government. When this happens, it has implications for the composition of the Cabinet. LSE Public Policy Group research by Patrick Dunleavy and Anne White shows that when decisions about Departments are made for party management and personnel reasons are very unlikely to deliver real public benefit.

Figure 1: Departmental changes in Whitehall from 1979 to 2009

Source: White, Anne and Dunleavy, Patrick (2010) Making and breaking Whitehall departments: a guide to machinery of government changes. Institute for Government; LSE Public Policy Group, London, UK.

The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee have concluded, after countless hours interviewing Civil Servants, former Ministers, and close observers of the process, that reshuffles are damaging not just to the effectiveness of individual Ministers, but also encourages what is dramatically termed a ‘kind of paralysis’ across Government.

John Reid, who famously occupied eight Cabinet positions in 8 years, told the Committee; ‘I am not a great fan of the annual reshuffle-type thing’ adding ‘In an ideal world you would spend a few years in each job’. Reid’s criticism is particularly telling, as more than any other Minister in recent years, he was able to further his career and ascend the Ministerial ladder in part because of a culture of perpetual Ministerial reshuffling.

Lord Heseltine, answering in the same evidence session as Clarke and Reid, said: “I cannot conceive of a situation where the pressures that build up both for more action and for political success within our system avoids there being reshuffle processes”, he pointed specifically to the circumstances, on the relative rebalancing, the success or otherwise of the Government and the economic pressures on the Government at the time.”

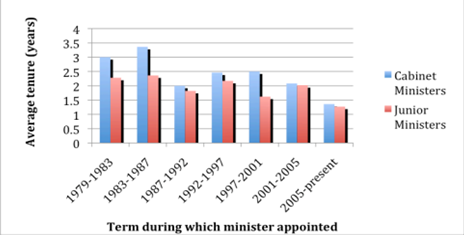

Under the previous Government, some tenures were so short as to be almost laughable, with Stephen Byers famously lasting five months as Chief Secretary to the Treasury. Indeed, the average Ministerial tenure between the 2005 and 2010 general elections, according to research from Demos, was 1.3 years (see figure 2 below).

Figure 2 – Average Ministerial Tenure, 1979 – 2008

A 5 year Cabinet term would also create fewer opportunities for career progress for those MPs wishing to become Ministers. While this may not be a bad thing in and of itself, it could further deter good quality individuals from pursuing a career as an MP, or even seeking to work hard and impress.

Despite this, it is nearly impossible to find principled reasons to prevent Ministers from becoming experts in the policy areas for which they have responsibility, and allowing them to forge good relationships with their officials and the stakeholders in the sector. David Cameron, to his credit, appears to recognise this, and has resisted the temptation to chop and change unduly, perhaps even being too reluctant to wield the knife when the pressure to move individual Ministers looks unbearable.

Whether he has made the right decision each time is open to debate, but the current Government seems to have struck a defensible balance between ‘freshening things up’ and allowing Ministers space to grow into their roles. No doubt to the chagrin of those occupying PPS and Junior Ministerial positions who may have expected to ascend the Ministerial ladder more quickly.

Perhaps a 2.5 to 3 year minimum term might be a better solution, which would allow Ministers to grow into their roles, while allowing enough in the way of turnover to freshen things up, introduce new talent, and avoid the flipside of the ‘experience’ coin – stagnation and the dreaded departmentalitis.

The Committee report also recommends that there should be a specific, experienced Minister operating from the Cabinet Office who would be responsible for ministerial development, managing departmental handovers, offering Ministerial training, feedback and appraisal. Interestingly, the Committee thought this could encourage a more rounded and objective assessment of the virtues of a particular Minister beyond their personal or political ties. This proposal, while undoubtedly controversial, has much to be said for it, and while it failed to find full favour amongst the members of the Committee, it is nonetheless something that the Government should give serious consideration.

The Committee has made clear that the way we do reshuffles need to change if we are to have better Ministers, better policy, and better Government. But we have to keep in mind that a certain amount of ‘churn’ is unavoidable, with Ministers – in our adversarial political system –prone to quitting or being forced out because of scandal, failure, or simply fatigue. So while a five year ministerial term is an attractive idea for a number of reasons, the unintended consequences could outweigh the positives

Sean Kippin is Managing Editor of Democratic Audit, and is one of two people responsible for DA’s day-to-day management, website, blog and wider output. He received a First Class (Hons) Degree in Politics from the University of Northumbria in 2008, and an MSc in Political Theory from the London School of Economics in 2011.

From 2008 to 2012 he worked for the Rt Hon Nick Brown MP in Newcastle and in the House of Commons. He has also worked for Alex Cunningham MP, the Smith Institute think tank, and as an intern at the Co-operative Party. He has been at Democratic Audit since June 2013, and can be found on twitter at @se_kip

This blog was originally posted on the LSE’s British Politics and Policy Blog, and can be viewed here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.