Turnout at European Parliament elections is likely to continue to decline in the coming decades

Turnout levels at elections to the European Parliament have fallen since the 1970s. Yosef Bhatti and Kasper Møller Hansen note that turnout is particularly low among younger citizens and that this appears to be a permanent generational effect, rather than simply a part of the voting ‘life cycle’. This is likely to present a demographic challenge for turnout levels at future European Parliament elections.

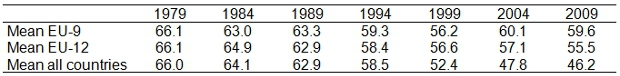

The 2014 European Parliament Elections are rapidly approaching. One thing to look for is how the voter turnout develops. Political scientists have rightly been concerned with the decline in turnout in most Western countries over the last couple of decades. Elections to the European Parliament (EP) are no exception to this pattern. As our Table shows, since the first direct elections in 1979, turnout has declined to a level where it can be regarded a serious threat to the legitimacy of the European polity. In 1979 the average turnout was about 66 per cent whereas it was only 46 per cent in 2009 (un-weighted averages). Even when we take into account that the composition of countries has changed over time, there has been a substantial decline (6-7 percentage points, 3-4 percentage points if we discount the first elections in 1979).

Table: Average turnout at EP elections (1979-2009)

Notes: The reported means are un-weighted averages of the country level turnout. In the EU-9 and EU-12 means Germany has been excluded due to the reunification. Source: European Parliament

We are not going to make predictions specifically about the 2014 Elections as it is extremely hard to predict turnout at specific elections (though we do think that voter turnout will decline substantially in our own country, Denmark, where it increased in 2009 due to a simultaneous referendum). Instead we will describe some general trends that will likely influence EP voter turnout in the long run.

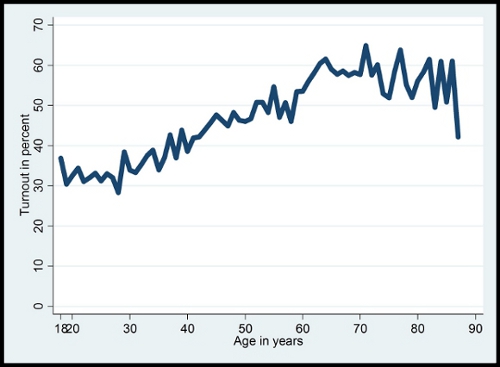

One striking thing about voter turnout to EP elections – and most other types of elections in the Western world today – is the strong relationship between age and turnout, as depicted in our Chart below. The percentage of young eligible citizens who vote is only about half of the percentage for middle-aged to old citizens (there is some uncertainty about the precise size of the difference due to the self-reported nature of the voter turnout data).

Chart: Relationship between age and voter turnout at the 2009 EP elections

Notes: Respondents in each country are weighted to match actual turnout. No country weight is applied, so the countries weigh approximately equal. It should be noted that the figure is based on self-reported turnout. Source: European Election Studies, 2009 pooled file

The relationship is a problem from the perspective of equality as it means that the young may ultimately have less influence on EP decisions. However the future effects of this disparity are less clear. It might be that the low turnout seen in younger generations will continue over time. Alternatively, the effect might reflect a political life-cycle, with younger citizens becoming more likely to vote as they grow older. Which explanation – generational or life-cycle effects – accounts for the difference in turnout levels?

As it turns out, it reflects both factors. Young individuals have always voted less than older adults, but today’s younger citizens still vote substantially less than earlier generations. In fact, the current generation of young adults seem to turnout 10-15 percentage points less than the baby boomer generation at EP elections (when taking age and period effects into account) and the gap to the pre-war generation is even bigger.

This is a serious challenge for EP elections as the pre-war and baby-boomer generation comprise 40-50 per cent of the electorate in most European countries in 2010. That number will, for obvious reasons, decline gradually towards zero over the next decades as the new generations replace older ones in the electorate. This means that unless current generations start to vote in higher numbers, or future generations become more politically active, generational replacement alone will decrease voter turnout to EP elections by a couple of percentage points over the next decade and substantially more if we look two or three decades ahead. In other words, EP elections (like many national elections) face a demographic challenge.

What to do about the challenge? This is where it gets tricky. There are probably no quick fixes. The largest potential gains in turnout probably relate to things that are very difficult to change: general political socialisation, citizens’ perception that EP elections are less important than national elections, knowledge about EP elections, and lack of national media attention surrounding the elections. However, there are some short term measures that could work. A large body of research by American political scientists Donald Green, Alan Gerber and others indicate that it is to some extent possible to convince citizens to vote by door-to-door campaigns and social pressure appeals. Of course these measures are costly to carry out and parties are probably not willing to spend the same resources on EP elections as for national elections. Newer studies show some potential in using online social networks as it is less costly and makes it possible to reach larger parts of the population.

We think it could be interesting to test these traditional and new measures in a European context and especially to look at what types of appeals work in an EP setting. None of this will likely skyrocket EP election turnout, but perhaps it can be a contributing factor to stabilising it at the current level, or at least slowing the rate of decline.

For a longer discussion of the topic covered in this article see the authors’ recent article in Electoral Studies.

Note: This post originally appeared on EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position ofDemocratic Audit, EUROPP, nor of the London School of Economics.

About the authors

Yosef Bhatti – University of Copenhagen

Yosef Bhatti – University of Copenhagen

Yosef Bhatti is an Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science,

University of Copenhagen. His research centers on voter turnout.

Kasper Møller Hansen – University of Copenhagen

Kasper Møller Hansen – University of Copenhagen

Kasper Møller Hansen is a Professor, Department of Political Science,

University of Copenhagen. His core areas of research are voter turnout,

public opinion and election campaigns.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Demographic change means turnout at European Parliament elections is only heading in one direction, it appears: https://t.co/5IBhlc9ais

@democraticaudit: Demographic change means turnout at European #Parliament elections is only heading in one direction https://t.co/jGqXux1EaO

Turnout at European Parliament elections is likely to continue to decline in the coming decades https://t.co/ZyguQz9qUO

@democraticaudit: Turnout at European #Parliament elections is likely to continue to decline in the coming decades https://t.co/wcylMlEHg5