Men only? The parliamentary Liberal Democrats and gender representation

The Liberal Democrats have both the lowest percentage and number of women MPs among the main parties. With those seats vulnerable due to their slim majorities, Elizabeth Evans questions whether a parliamentary party dominated by white men that claims to stand for equality can claim credibility.

The recent announcement by Sarah Teather that she is to stand down from her Brent Central constituency in 2015 is a serious blow to the Liberal Democrats’ chances of retaining the seat at the next election -incumbency being particularly important to the electoral success of the party. However, perhaps more worrying is the fact that her decision will surely decrease the overall number of women Liberal Democrat MPs (currently they number 7, just 12% of the parliamentary party).

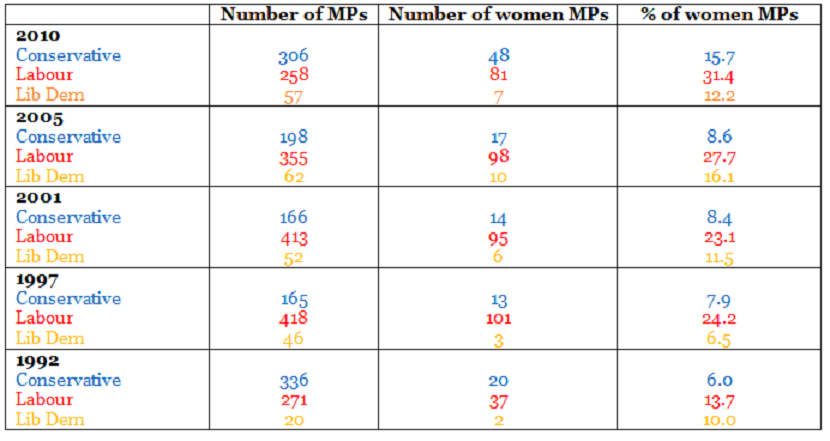

Whilst there are undoubtedly some (both inside and outside of the party) who would argue that the Liberal Democrats have bigger things to worry about than the number of women MPs, there is no denying that their record on women’s representation is poor (see table 1 below) and that this is at odds with their claims to be a party that prioritizes equality.

In addition to the loss of Teather, Annette Brooke MP (Mid Dorset and Poole North, majority 269) has also announced she will be standing down in 2015; this leaves just 5 incumbent women MPs fighting seats in 2015. And those women MPs have tough fights on their hands: Lorely Burt, Solihull, majority of 175; Tessa Munt, Wells, majority of 800; Jo Swinson, East Dunbartonshire, majority of 2184; Jenny Willot, Cardiff Central, majority of 4576; and Lynne Featherstone, Hornsey and Wood Green, majority 6875. Indeed, given that the two ‘safest’ seats, Cardiff Central and Hornsey and Wood Green, will inevitably be top target seats for the Labour party, for both strategic and symbolic reasons, this means that the prospects for maintaining, let alone increasing, the current percentage of women are bleak.

The table above illustrates that it is not just the Liberal Democrats who have struggled to present a more gender balanced parliamentary party; indeed, neither the Liberal Democrats nor the Conservatives have got anywhere close to Labour’s record when it comes to the number and percentage of women MPs. Whilst Labour’s success has been down to the adoption of the all-women shortlist strategy, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats have long been wary of going down that road.

For the Liberal Democrats the opposition to sex-based quotas rests on four principle arguments: 1) the party is opposed to the strategy on ideological grounds, quotas being seen as fundamentally illiberal; 2) the party operates through a federal structure which ensures local party autonomy over the selection process; 3) the party has insufficient numbers of women putting themselves forward for selection, thereby making all women shortlists unworkable; and 4) the party does not have any safe seats where quotas could be adopted to guarantee an increased presence of women.

It is certainly true that now would be a difficult time for the party to re-open the divisive debate on all women shortlists: a recent poll of party members conducted by Lib Dem Voice confirms that the party’s grassroots remain opposed to quotas. Although Nick Clegg has observed that he is not ‘theologically opposed’ to the mechanism, in the party’s post-coalition world, the grassroots is frequently observed to be at odds with the leadership, which would make it even harder for the centre to impose change at this particular time of electoral uncertainty.

I have argued previously that whilst the party does indeed have fewer women than men applying for seats, there are not so few women available as to make all-women shortlists unworkable. Yet with the party likely to be focussed on defence rather than attack at the next election, there are fewer opportunities to concentrate resources on winnable and target seats with women candidates. As such, the party will need to direct its resources towards seats where women MPs are in place.

The party’s efforts to increase the number of women MPs has principally revolved around training and mentoring opportunities, but this has not yielded satisfactory results. At the last general election, women constituted just over 30% of Liberal Democrat candidates fighting seats requiring a swing to win of 5% or less. Although the party selected 4 women to fight held seats where the incumbent was standing down (out of 7), none of them was elected (reinforcing the importance of incumbency for the party).

At the aggregate level both the number and percentage of women candidates fielded by the party decreased from 2005. Looking forward to 2015, the low numbers of women selected thus far reinforces the idea that the party has yet to take the issue of women’s representation seriously; the party’s latest update sets the current selection rate at 68% male. Although, the prospect of having just one or two women MPs appears to finally be causing some concern amongst senior party figures.

Prior to 2010, Russell and Fieldhouse identified that one of the main problems for the Liberal Democrats was one of credibility; now they are in office they have to some extent overcome that particular challenge. However, questions remain whether a parliamentary party dominated by white men that claims to stand for equality and fairness can really claim to be credible.

—

Note: this article represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. Shortened URL for this post: https://buff.ly/19ehJup

Dr Elizabeth Evans is a Lecturer in Politics at University of Bristol and the Co-convenor of the women and politics group

Dr Elizabeth Evans is a Lecturer in Politics at University of Bristol and the Co-convenor of the women and politics group

This post is part of Democratic Audit’s Gender and Democracy series, which examines the different ways in which men and women experience democracy in the UK and explores how to achieve greater equality. To read more posts in this series click here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Men only? The parliamentary Liberal Democrats and gender representation https://t.co/g1l9V3fHIS

Or male ones! || RT @democraticaudit: The Liberal Democrats could have NO female MPs left after the next election https://t.co/KlfiiDFpXj

The Liberal Democrats could have NO female MPs left after the next election https://t.co/AO0aQL2gYB

@markpack Hi Mark, this might be of interest: https://t.co/Tqnk9W2ILP

@TheStaggers @NewStatesman @GloriaDePieroMP there’s a very good chance they won’t have any women left post-2015 https://t.co/Tqnk9W2ILP

@chamiltonbbc and then, of course, there is the way the Lib Dems do things https://t.co/o8Tz3UTIWa Enough said!