The iPod generation demands a more bespoke version of democracy

Voters are no longer content with the package deals offered by political parties in elections, argues Matt Qvortrup. Like music fans who prefer individualised playlists to pre-packaged albums, citizens want to choose individual policies that reflect their views – not just the party platform. This, he suggests, is a reason to move toward direct democracy and make greater use of referendums.

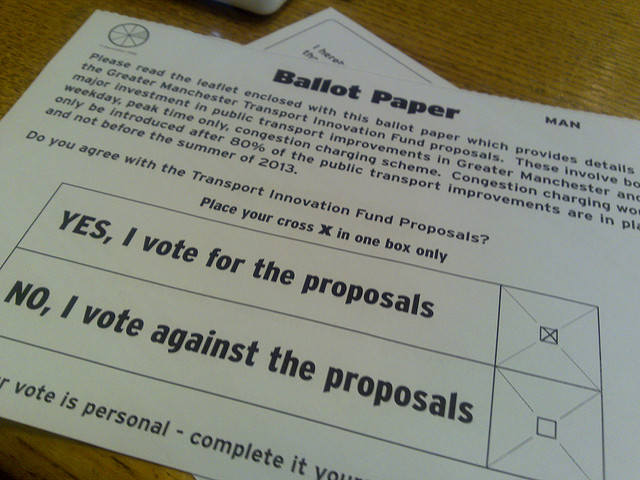

Greater Manchester voters rejected a local congestion charge in a 2008 referendum. Credit: Frankie Roberto (CC BY 2.0)

In the middle of the 20th Century, political theorists were sceptical of the people. The Austrian theoretician Joseph Schumpeter was summed up the general consensus when he wrote, in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, that, “Democracy means only that the people have the opportunity of accepting or refusing the men who are to rule them”.

70 years on, the view was very different. We are no longer content with the political package-deals offered by political parties. We want to have our political cake and to eat it too; we want to vote for political parties, but we also want to have choices if these parties do not represent us. For example, it is possible to be a Labour supporter and yet a Euro-sceptic.

All this reflects a general trend towards more choices. The way we consume products is beginning to be reflected in the way we participate in politics. This is how the explanation goes. Once we were content with package deals. Consumers used to buy music albums and even box-sets. Nowadays, they download selected tracks for their MP3 players. Once, we were happy to watch pretty much whatever was on TV. Now, they want individual choices; they choose different camera angles when, watching live sport on the television, personalise their Volkswagen ‘Beetle’ and their iPhones. The list is limitless. It is, perhaps, in this context of the ubiquitous individualised shopping lists, that we should see the demand for direct democracy.

For political parties and the system of representative government is in many ways representative of the old system of one-fits-all; the system under which we were content with package deals. This system is arguably no longer acceptable for the individualised consumer.

The traditional system of ‘party-democracy’ is at odds with an electorate which is more interested in single issues, causes and campaigns. It is in this context we should see the debate about direct democracy. The debate is not about traditional models of engagement and deliberation, though that too. What is at stake is an urgent upgrade of the political system’s hardware (its constitutional arrangements) as well as its software (the way we do politics).

Karl Marx once argued that revolutions occur when there is a discrepancy between the fundamental underlying structures of society and the political superstructure. When the economic system changes, when the way we consume, produce and interact in the marketplace changes, then begins “an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure”. That is, “at a certain stage of development the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production”.

Without carrying the analogy too far, we may be at a critical junction in history. The underlying structure of society, the way we thing, the way we consume and so on, is out of sync with the way we govern our societies. We live in the world of the individualised consumer, of mass information and choice, yet the political structures are still those of the collectivised society of the post World War Two era.

The referendum – at least on paper, provides the ‘political consumer’ or ‘customer’ with the opportunity of selecting their personal choices, and thus provides another avenue – another input -into the political system. But this does not mean that the old system is entirely obsolete.

The system of representative government is not doomed because we introduce mechanisms of direct democracy as a complement or as a safety valve. Politically we want to have our cake and eat it; citizens are content with voting for political parties, but they are no longer willing to transfer their all powers to their representatives. It seems, to use a celebrated philosophical argument, that they are in agreement with Rousseau who famously noted in The Social Contract that “the English People believes itself to be free; it is gravely mistaken, it is free only during the election of Members of Parliament; as soon as the members are elected the people are enslaved”.

Referendums do not always work. The voters can be hoodwinked into adopting measures and there are examples of minority repression, but there are also examples of measures passed by parliaments that have led to oppression and discrimination of minorities. Likewise, while there are examples of populist measures to lower taxes, there are also a fair number of cases of referendums in which the voters have voted for higher taxes, for examples of voters supporting higher taxes both in Britain (Milton Keynes) and in California. Overall referendums have worked if they have been held on exceptional and salient issues.

Referendums have not – and cannot – replace representative democracy. But they provide a corrective – or a complement – at a time when the political parties fail to adequately represent the views of the citizens. In an earlier time when there was greater congruence between the views of the voters and the position of the political parties there was less need for referendums. But as the party-systems began to defreeze in the early 1970s there was a need for a mechanism that provided an outlet for frustrations and a safety-valve when politicians did not represent the voters. This and the much debated tendency towards individualised consumers in society more generally, and it is not surprising that voters increasingly request mechanisms of ‘bespoke democracy’.

Some might fear that this tendency towards mechanisms of direct democracy is ill-advised as voters – allegedly – have insufficient knowledge to decide issues and as they might fall prey to populist demagogues.

The empirical evidence does not substantiate this fear. While there have been examples of ill-considered decisions, the track-record of referendums is – on the whole – a not populist. The referendum – and its close relative the citizens’ initiative – has not resulted in the introduction of populist measures.

It might be argued that the voters –when given the choice have acted responsibly. In the early 1980s politicians spoke of supply-side economics. According to Say’s Law, a law of economics named after the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say: ‘A supply creates its own demand’.

What was true for economics seems also to be true for democracy: a greater supply of democracy creates a demand for political participation. To quote the late British politician Keith Joseph: “if you take responsibility away from the people you make them irresponsible – if you give responsibility to the people they become responsible”.

More direct democracy gives people more responsibility, and the empirical evidence in this very brief chapter suggests that these opportunities to participate generally have made them more not less ‘responsible’!

Note: This post represents the views of the author, and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink: https://buff.ly/H81W3N

Dr Matt Qvortrup is a fellow at The British Institute of Contemporary History and a Senior Lecturer at the UK Defence Academy. In 2012 he won the Oxford University Law Prize. Dr Qvortrup’s book Direct Democracy: A Comparative Study of the Theory and Practice of Government by the People, is published by Manchester University Press.

Dr Matt Qvortrup is a fellow at The British Institute of Contemporary History and a Senior Lecturer at the UK Defence Academy. In 2012 he won the Oxford University Law Prize. Dr Qvortrup’s book Direct Democracy: A Comparative Study of the Theory and Practice of Government by the People, is published by Manchester University Press.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.