Online misogyny prevents women from fully participating in democracy

Many women, including a number of high-profile British politicians, have been the targets of misogynistic abuse via Twitter and other online forums. In this post, Laura Bates of the Everyday Sexism Project shares evidence of abuse and argues that this culture contributes to reduced participation by women in politics. [Please be aware that this post contains potentially offensive material].

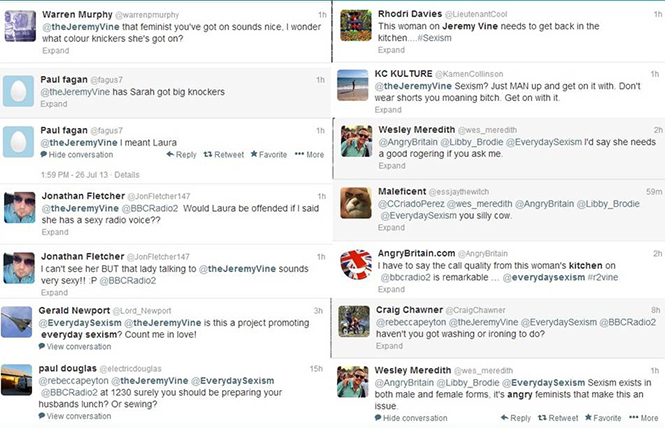

Women have been the targets of misogynistic abuse via Twitter and other forums. Credit: Laura Bates/Women Under Seige

There are two major barriers to women’s full participation in the democratic process in the UK at the moment—the first relates to their taking part in the vital and shaping process of grassroots activism, and the second to their participation in more traditional political careers.

The process of democracy in the UK is shaped by exciting and vibrant activism, across a whole range of issues, from climate change to women’s equality. Increasingly, in the digital age, this activism is both organized and carried out using online resources such as social media. The Internet is a vital tool in raising the voices of those who have frequently previously been silenced, and allowing marginalized and disadvantaged groups a platform to campaign for their rights. But the experience of participating in an online campaign or in online activism is manifestly different for men than it is for women.

Simply by participating in online spaces, women are faced with a barrage of content that can make it a hostile and dangerous environment for them. Rape jokes, domestic violence memes and entire forums dedicated to violent misogyny exist close to the surface, with images like these cropping up on popular social networking sites:

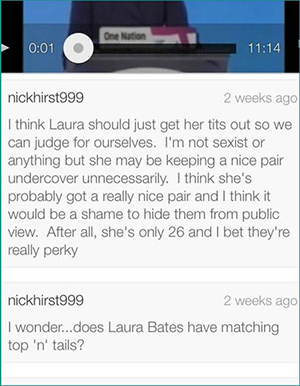

But more specifically, women who dare to use their voices to discuss politics or take part in democratic processes online tend to face a barrage of online abuse. I have experienced this myself almost constantly since starting the Everyday Sexism Project two years ago. It ranges from online harassment and sexist responses to political debate which utterly ignore the content of said debate in favour of outright misogyny to specific and explicit threats of rape, violence and death. These threats pour in through Twitter and through other online avenues. The cumulative impact of these is significant.

It might be easy from the outside to dismiss them as harmless trolls but when you are daily wading through explicit detailed descriptions of how you should be raped and murdered and how the writers are able to track you down, and when the messages diversify and start threatening to rape your family members instead, the impact is considerable. For many women, particularly younger women or those more vulnerable members of society whose voices most urgently need to be nurtured and encouraged within the democratic process, this would likely drive them out altogether.

The problem with this vitriolic stream of abuse is that there is currently little to no protection or recourse. The police told me last year, when I presented them with a large collection of these messages, that there was absolutely nothing they could do. So women are faced with the stark choice of dealing with such abuse, or withdrawing their participation in online activism. This is a fast-growing problem and the police have not yet caught up.

The problem with this vitriolic stream of abuse is that there is currently little to no protection or recourse. The police told me last year, when I presented them with a large collection of these messages, that there was absolutely nothing they could do. So women are faced with the stark choice of dealing with such abuse, or withdrawing their participation in online activism. This is a fast-growing problem and the police have not yet caught up.

It would be extremely helpful to see more support for cracking down on these issues, for actually tracing IP addresses of perpetrators and following through, when somebody has committed the criminal offence of threatening rape or murder. It would also be helpful to see international cooperation on these issues—the Internet is able to cross physical borders in a way that law enforcement has yet to catch up with, meaning that those sending me threats from IP addresses outside the UK or even one website which was openly coordinating such attacks against me, were apparently outside the remit of the UK police.

Now let us turn to the second major issue.

Here in the UK, we are still suffering from major barriers to women’s full participation in politics itself. Even now, in 2013, less than one in four MPs is female, and women make up only around 12 percent of council leaders and 17 percent of the cabinet. The UK comes in at 58th in the world for gender equality in political representation. And everywhere young women look, they receive the message that politics is a men’s game, and that women in politics are not taken seriously.

This is partly an international problem, From the treatment of Angela Merkel, these girls have learned that even if Forbes magazine labels you the most powerful woman in the world, it will still be considered appropriate to focus articles on your “frumpy power suits” and “silly pageboy haircut.”

From Hillary Clinton’s time as secretary of state, they have learned that women in politics will be questioned, not on their political beliefs, but on their favourite designers, and that that they must prepare to be arbitrarily lambasted either for being too feminine or not feminine enough.

From Sarah Palin’s vice presidential campaign, they have learned that no matter what your ideas on the environment or the economy, your immortalization as a blow-up doll will guarantee that voters remember you best as a sexual object.

And from the experience of French minister Cecile Duflot, they have learned not to dare wear a perfectly normal dress with elbow-length sleeves if they want their political point to be heard above the catcalls from fellow MPs.

But it is also the case here in the UK, where girls have learned that MPs’ breasts are fair game for public debate; that a newspaper can bully a female politician by naming a Page 3 picture after her; that when two female politicians disagree, the result is not a debate but a “catfight”—and that they are not MPs, but Tory “blondes.”

From our own Prime Minister, they have learned that a female politician who dares to show passion in the House of Commons will be reprimanded by being told to “calm down, dear.” From MP Austin Mitchell, they have learned that it is acceptable for politicians to make statements like, “A good wife doesn’t disagree with her master in public,” and to call their female peers “good little girls” without repercussions. Last year, after former MP Louise Mensch disagreed with something her husband said about her resignation, Mitchell wrote, in a message that appeared on his own official MP website, “Shut up Menschkin. A good wife doesn’t disagree with her master in public and a good little girl doesn’t lie about why she quit politics.”

From articles on “Cameron’s Cuties” and “Blair’s Babes” to “Hollande’s Honeys,” girls are learning that cabinet reshuffles lead to new male members being grilled on their past voting records while the women are described as “glamorous political beauties” and column inches devoted to their high heels.

And the impact of all this is that girls and young women are receiving the message, loud and clear, that politics is not for them. Here is just a small selection of their entries submitted directly to the Everyday Sexism Project over the past 18 months alone:

“I was on a busy train reading my Comparative Government textbook (I’m a politics student) when the man opposite me commented ‘That looks a bit complicated for you love, why don’t you try something a bit simpler?’”

“At school, a teacher said it was good that ‘masculine’ girls like me wanted to go into politics because most women were only there because men let them, to ‘shut up the feminists for a bit’”

“I was told ‘if you want to be in Politics, you could be an MP’s secretary’”

“Recently told by stranger I’m ‘too pretty to be involved in politics.’”

“I took A-level politics…I had worked hard to prepare for a debate in which I was the only female in my team. While providing a counter-argument my teacher stopped me and asked the males in my team whether they were going to let a woman do all the talking.”

“Went on a trip to the Houses of Parliament as part of our Government & Political Studies A-Level… We were given a tour… The guide said ‘There is a book shop over there, there are recipe books for the girls.’”

Of course this isn’t all fuelled by sexist media portrayals of female politicians, or sexist remarks by their male peers, but these are a major influence on the formation of public attitudes and stereotypes. And the media portrayal of women as passive sex objects, while men do real jobs and run the world, as exemplified by Page 3 of the Sun are also contributing factors. We urgently need to see more concrete steps from government in attempting to address the discriminatory nature of our current media portrayal of both female politicians and women more generally, if we truly want to move forward in removing the barriers to women’s full participation in the democratic process.

The immediate response to both of these issues—online abuse and the misogynistic media portrayal of women, is the cry that this is all just “freedom of speech,” and of course it is right and proper that the freedom of speech and freedom of the press should be protected within a democratic society. But it is also right that women should be allowed the same platforms and opportunities as men to contribute to that democratic society, and that is not the case when their voices are being silenced—their freedom of speech affected—by online abuse and an enormously unequal media portrayal. Somehow the freedom of their speech is something we rarely hear spoken about.

Note: This post was originally published on the Women Under Siege blog. It gives the views of the author, and not necessarily those of Democratic Audit or the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink: https://buff.ly/1asV2zs

Laura Bates is the founder of the Everyday Sexism Project, a collection of over 45,000 people’s experiences of gender imbalance. She writes regularly for the Guardian, the Independent, Grazia, and Red Magazine among others. Laura is also Contributor for Women Under Siege, a New York-based organisation working against the use of rape as a tool of war in conflict zones worldwide.

Laura Bates is the founder of the Everyday Sexism Project, a collection of over 45,000 people’s experiences of gender imbalance. She writes regularly for the Guardian, the Independent, Grazia, and Red Magazine among others. Laura is also Contributor for Women Under Siege, a New York-based organisation working against the use of rape as a tool of war in conflict zones worldwide.

(Author image copyright © Claude Schneider)

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.