Party leaders are getting younger, but Cabinet Ministers are not

During the 20th Century, the average age of Prime Ministers upon assuming office has trended downwards. However, according to Judi Atkins, Timothy Heppell and Kevin Theakston, the same is not true of Cabinet Ministers, with the average age remaining relatively consistent since 1945 across both main parties. The authors argue that the claim that we are witnessing the rise of the novice Cabinet minister is perhaps more a consequence of the personalisation of politics than evidence of an emerging ‘cult of youth’.

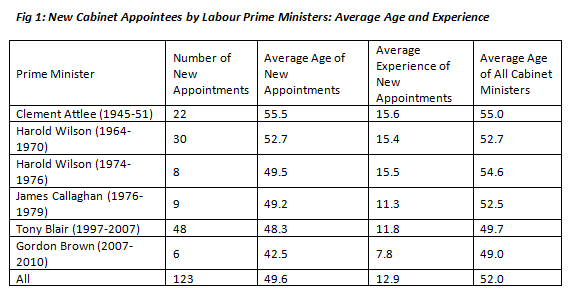

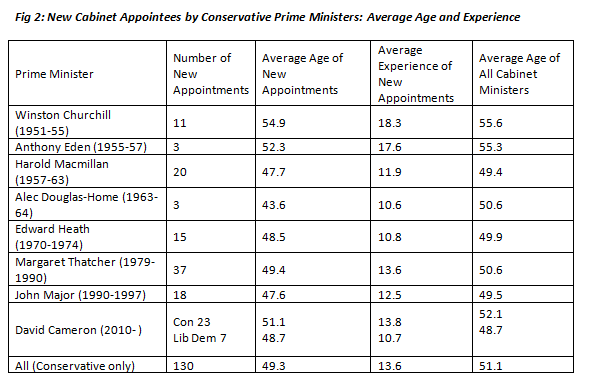

A number of commentators have observed that today’s Cabinet ministers are younger and less experienced than their predecessors. To support this claim, they cite examples from the Brown government, notably Ruth Kelly, David Miliband and James Purnell, who left politics at the age of 40, 47 and 38 respectively. This raises the question of whether there a trend towards youth and inexperience amongst those who reach Cabinet level. In a recent article, we addressed this question by identifying the age and prior parliamentary experience of post-war Labour and Conservative ministers at the point when they were elevated to the Cabinet.

The figures show a small decline in the average age and parliamentary experience of new Cabinet ministers when comparing Churchill to Cameron, but there are fluctuations in between that are not evident in the Labour data. In contrast, there is a clear downward trajectory from 55.5 years of age under Attlee to 42.5 under Brown, and from 15.6 to 7.8 years of experience. Although this tendency is less pronounced in the Conservative data, it should be noted that the highest averages for both were recorded by Churchill. So, if Cameron were to form a second administration, we can assume that there would be an influx of younger and less experienced Cabinet ministers. This is because long periods in opposition will increase the averages when re-entering power (see, for example, Labour in 1997), while age and parliamentary experience decrease over consecutive terms of office.

Placing this debate in its historical context, we find that high-fliers have always started climbing the ministerial ladder relatively young. In 1945-83, the average age on first appointment of all junior ministers was 46. However, the figures for those who reached the Cabinet are lower: 41 for Labour and just over 40 for Conservatives. Likewise, those junior ministers under Thatcher and Major who eventually made it to the Cabinet received their first junior job at the average age of 42, compared to 47 for those who never got above the Parliamentary Secretary level. Meanwhile, in 1997-2010, the average age on first junior appointment of those who subsequently reached the Cabinet was 45, compared with 49 for those who failed to do so. That these figures were slightly higher in the Blair/Brown era than in the Thatcher/Major period indicates there is no broader trend towards youth.

While the age and parliamentary experience of party leaders has decreased since 1945, this tendency is less pronounced for members of the Cabinet and even less evident for junior ministers. One explanation is that public profile is correlated with ‘noviceness’: the more prominent the role, the younger and less experienced its incumbent is likely to be. This in turn may be linked to the rise of the mass media, which has led to an intensification of political marketing and a greater focus on the party leaders – a phenomenon termed the ‘personalisation’ of politics.

The televised debates of 2010 reinforced the notion that the leader is the public face of their party and the embodiment of its core values. Given the imperative of modernisation in British politics, from Wilson’s pledge to harness the ‘white heat’ of technological revolution to Cameron’s vision of a ‘modern, compassionate Conservatism’, it is hardly surprising that today’s leaders are younger than their predecessors. Given that youth is inextricably associated with this spirit of change and renewal, an older statesman might struggle to represent these qualities convincingly, placing at risk the credibility of their party.

Cabinet appointments also contribute to a party’s image, and indeed Brown sought to renew his government by appointing the youngest and the least experienced Cabinet of the post-war era. However, youth is not normally a major consideration, in part because the role of Cabinet minister is not ‘personalised’ to the same extent as the party leadership. Although still a focus of media attention, Cabinet ministers are not expected to embody the values of their party or even to be particularly likeable. Rather, they are required to ‘behave in a way that upholds the highest standards of propriety’ their public image is of secondary importance.

Most junior ministers have a lower public profile than their senior colleagues and media engagement is generally a minor part of the job. After all, dozens of junior ministers cannot provide a focal point for public attention equivalent to that of the prime minister and would soon generate mixed messages. Consequently, it is unsurprising that junior ministers have remained almost untouched by the growing personalisation of politics, and that there is no discernible trend towards the ‘novice junior minister’.

Overall, we find no significant downward trajectory in the age and experience of Cabinet ministers since 1945. It may be that the intense focus on novice party leaders has shone a spotlight on the select group of younger Cabinet ministers, leaving the older majority in the shadows. If so, the claim that we are witnessing the rise of the novice Cabinet minister is more a consequence of the personalisation of politics than evidence of an emerging ‘cult of youth’.

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1aoFIFU

|

Dr Judi Atkins is a Research Fellow in British Politics at the University of Leeds. |

|

Dr Timothy Heppell is Associate Professor of British Politics at the University of Leeds |

|

Professor Kevin Theakston is a Professor of British Government and Head of the School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Interesting stuff and useful charts. But I’m not sure I agree with the premise. Don’t the charts show that the average age of cabinet members has gone down over time by more than 10%? And the amount of experience by considerably more? Or am I misinterpreting them?

And given that life expectancy has increased significantly (by 10% in the last thirty years alone) the discrepancy becomes even more dramatic ‘in real terms’.

For me the issue is not whether our ministers are significantly younger but whether it matters or not. I have (inevitably) blogged on the subject because I think it is really interesting:

https://www.alexanderstevenson.co.uk/modern-irrationality—leaders-are-becoming-younger.html

Averages so rarely tell the full story that whenever I see a story like this I wonder, “yes but what about the spread”?

For instance having Ken Clarke in the Cabinet will substantially raise the average experience and “compensate” for a number of inexperienced ministers. Likewise if Miliband was to bring Jack Straw into his shadow cabinet, its average experience (particularly “in office” experience) would rise substantially.

Looking at some measures of spread will also reveal whether or not a Prime Minister is gathering a group of “like-aged” (= like-minded?) people around him in cabinet.

With younger Prime Ministers you might expect them to be nervous of slightly older/more experienced cabinet rivals, whilst being able to accommodate those now too old to personally mount a challenge.