Protections for the freedom of religion have improved over the last decade

In the 2012 Audit of Democracy, Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Stephen Crone, and Andrew Blick looked at the key issue of religious freedom in Britain. While the country remains relatively secular in practice, the British state is tied up by anachronistic historical relics such as an established church and the continued presence of Bishops in the House of Lords. Despite this, Britain has strengthened its protections against religious discrimination over the last decade or so.

The freedoms to practise religion, language or culture are not necessarily as directly connected to the formal political processes of a democracy as are other rights such as the freedom of expression and association. However, they are essential components in the free society that is required for the sustenance of genuine democracy. Moreover, there is an historic and ongoing connection between on the one hand, religious, linguistic and cultural rights, and on the other hand rights such as freedom of expression, which means that they cannot fully be considered separately from one another.

The freedom to practise religion has specific provision under Article 9 of the ECHR, which covers freedom of thought, conscience and religion. In the UK there is no formal concept of a secular state. The official position is that there is an established church (although not in Wales and Northern Ireland), of which the UK Head of State (i.e. the Queen) is the figurative head, and which has places in the House of Lords reserved for 26 of its bishops (with no such provision existing for any other faith group).

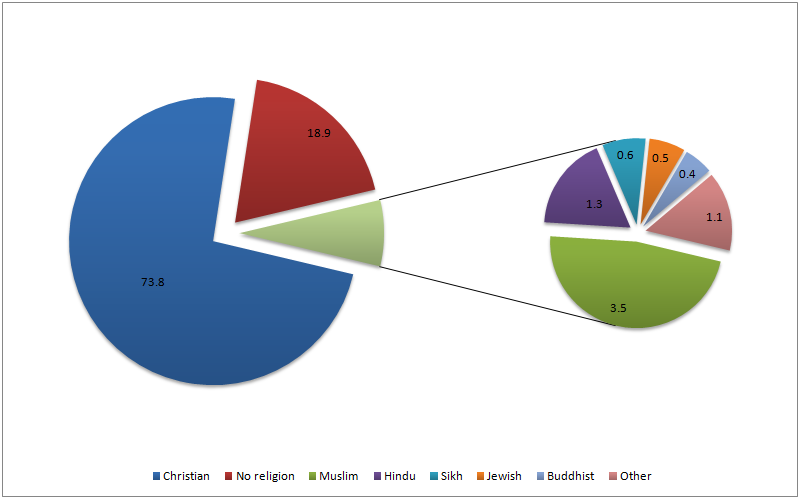

Proposals for a reformed House of Lords brought forward by the coalition would mean that the proportion of bishops within the new second chamber would actually be higher, though within a smaller overall house. Rules of succession to the throne ensure that only someone in communion with the established church can become monarch. As Figure 1 shows, the UK is a multi-faith society, with a considerable portion of the population holding no faith.

Source: Equality and Human Rights Commission (2010, p. 63)

While a majority (74 per cent) of UK residents describe themselves as ‘Christian’, the figure includes those who are only ‘culturally’ Christian. Many of those who describe themselves in this way do not practice Christianity, and may even be agnostic or atheist. There are also Christians from denominations other than the official one, such as Roman Catholics. According to a Populus poll published in February 2011, 54 per cent of people described themselves as Christian, a significantly lower figure than appears in Figure 1.3d, which again underlines that much religious identification in the UK is likely to be weak. Moreover, only 33 per cent of those self-identifying as ‘Christians’ reported religion as being important to them; while 36 per cent said that it was not.

Furthermore, 68 per cent of respondents indicated that they agreed with the statement ‘religion should not influence laws and policies in this country’. The existence of an ‘official religion’ could, in a sense, be argued to discriminate against all those who do not subscribe to it. However, in practice, public policy tends to promote equal provisions for different faith groups, including those of no faith, through measures such as providing for the establishment of faith schools alongside non-denominational schools.

Given the multi-faith and no-faith nature of the UK, protecting the freedom of religious belief and its interrelationship with other rights and anti-discrimination law is a complex issue, with competing claims to be reconciled. For instance, in the case of Ladele v London Borough of Islington 2008, a Christian registrar was threatened with dismissal after refusing to officiate for civil partnerships. She then claimed that she was subject to direct and indirect discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief. The initial employment tribunal found in her favour, but this ruling was reversed on appeal. During the period since the last Audit, there has been substantial legislative activity intended to enhance religious freedom:

- In 2003 the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations created a prohibition on both direct and indirect discrimination in employment on the basis of religion or belief. However an exemption was provided for employers with an ‘ethos based on religion or belief’, who can discriminate on the basis of religion or belief if being of a particular religion or belief is ‘a genuine occupational requirement for the job’ and where ‘it is proportionate to apply that requirement in the particular case’ (Regulation 7(3)).

- The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 outlawed the incitement of hatred on the grounds of religion or belief, through amending the Public Order Act 1986, which now defines religious hatred as ‘hatred against a group of persons defined by reference to religious belief or lack of religious belief’.

- In 2008 the common law offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel, which protected only Christianity, were abolished through the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008.

- The Equality Act 2006 prohibited discrimination on the basis of religion or belief in the provision of goods, facilities and services, the management of premises, education, and the exercise of public functions. Part 3 of the act provided for regulations made in 2007 outlawing discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the provision of goods and services, but provided an exemption for the ‘purpose of an organisation relating to religion or belief’. Significantly, however, this exemption is no applicable to organisations working within education and/or with public authority contracts; for instance, adoption agencies.

- Finally, the Equality Act 2010 consolidated a wide, disparate body of equality law, which was up until that point to be found in more than 100 different primary and secondary legislative provisions. The general intention of the act was to give consistent rights and protections to various different groups. Religion or belief was one of a number of ‘protected characteristics’ defined by the act – as well as age, disability, gender reassignment, race, gender and sexual orientation. Practices as well as policies can be deemed unlawful under the act. It also extends the requirement for public bodies to promote equality and sets out how this goal may be achieved – from the areas of race, gender and disability, to the additional protected characteristics in the act, including religion.

Some of these shifts provoked controversy. By including an exemption for employers with an ‘ethos based on religion or belief’, the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations could be seen as protecting the religious views of members of one group, at the expense of the rights of members of another. Further controversy was generated during the passage of the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006.

The act’s outlawing of the incitement of hatred on the grounds of religion or belief was interpreted by some as potentially damaging to the right of freedom of expression. Once again the difficulties involved in balancing different civil and political rights were apparent.

—

Note: This post is based on extracts from the 2012 Audit of Democracy, specifically section 1.3.3 Freedom of religion and rights of minorities. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/18lOW7L

—

Stuart Wilks-Heeg, Andrew Blick, and Stephen Crone are the authors of the 2012 Democratic Audit report.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

I don’t want freedom of religion in England. Religions are nothing more than political parties with fictitious, albeit vicious, deities attached. One particular religion makes killing a virtue, provided it is done in the furtherance of that religion. Of course I must not name that religion because that would be intolerably hateful and contradict the freedom of religion we all enjoy to the utmost.

What did the 2012 Audit of UK Democracy have to say about freedom of religion in the UK? https://t.co/Auz9Dp1FJR

How free are we to exercise freedom of religion in the UK? Find out what the Democratic Audit of 2012 had to say https://t.co/0HDJU1FQGK

Protections for the freedom of religion In the UK have improved over the last decade https://t.co/DGFZESsSud

Protections for the freedom of religion have improved over the last decade https://t.co/CL5GPljUy4