Constitutional amendments by popular initiative: lessons from Croatia’s constitutional outlawing of gay marriage

On 3rd December 2013, the Croatian public voted in support of adding a provision to their constitution which defines marriage as “a union between a man and a woman”. Croatians effectively voted to constitutionally entrench a ban on gay marriage. The prohibition of same sex marriage in the constitution is in itself is not particularly unexpected in Croatia, with a whole host of eastern European nations failing to recognise the marriage of same sex couples. What is perhaps more surprising, argues Christine Stuart, is the means by which it occurred.

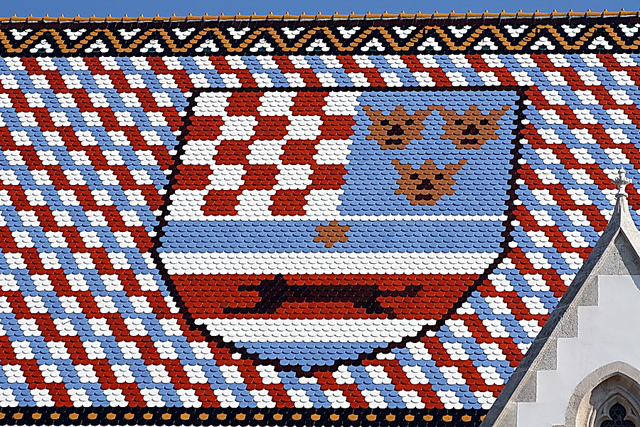

St Mark’s Catholic Church, Zagreb. 90% of Croatia’s population identifies as Catholic (Credit: Pilar Torres, CC BY 2.0)

Following the 2011 election, the new coalition government in Croatia announced their intention to expand the rights of same sex couples. In a country where approximately 90% of the population consider themselves to be Catholic, this decision was not well received by many religious groups. The response by Catholic group “In the Name of the Family” was to launch a public initiative to propose the constitutional entrenchment of the definition of marriage as being between a man and a woman. An overwhelming 750,000 citizens signed the petition calling for a referendum on the matter, almost 20% of all eligible voters in the country.

As per Croatia’s Constitution, Parliament is obliged to call a referendum when requested by 10% of the total electorate. So whilst the President and Prime Minister of Croatia both fiercely opposed the constitutional amendment, the 10% threshold was surpassed and the referendum went ahead. Two thirds of those who turned out voted in favour, and subsequently the government was forced to announce that the prohibition of same sex marriage in the constitution would go ahead.

Prior to the referendum taking place, Croatia already had a legal definition of marriage. Article 5 of the Family Act 2003 states “Marriage is a legally regulated community of a man and a woman.” So why the need for a constitutional definition? The reasoning behind defining marriage not only by law, but also in the country’s higher law, was to ensure that the definition of marriage became particularly difficult to change. To amend the constitution, a two thirds majority vote in Parliament is required. This is no mean feat, particularly with regard to controversial or divisive subject matters. With 13 parties currently represented in the Croatian Parliament, a supermajority becomes impossible without significant cross-party consensus. Thus defining marriage in the constitution had the purpose not only of limiting the rights of same sex couples, but also of ensuring that this limitation persists long into the future.

What makes this sequence of events in Croatia particularly noteworthy is that the change to the constitution was initiated not by the countries’ elected legislators, but by the public at large. There was such definitive popular support that the government has been forced into making a constitutional amendment that it doesn’t want to make. It could be argued that this is a sign of a healthy democracy, with decision making in the hands of the wider population. In this instance however, the wider population is a largely Catholic, heterosexual majority group. By voting to discriminate against the minority gay and lesbian segment of society, this bears more resemblance to a tyranny of the majority, than a healthy democratic practice.

The violation of the rights of a minority group is a dangerous precedent to set. This is clearly a concern for the Croatian government, who have responded by proposing an amendment to the constitutional provision that allows for popular initiatives to incite referenda on issues of constitutional change. The proposed amendment calls for a restriction on the issue areas which can be brought before a referendum, with the aim of prohibiting any future referenda on issues of fundamental rights and freedoms.

The Croatian government is right to have serious concerns about the use of referenda when it comes to issues of minority rights. A second popular initiative has since been launched in Croatia, this time collecting signatures in support of limiting the rights of the Serbian minority’s use of their own alphabet. Yet the governments’ response to alter the constitutional amendment procedure is in itself a questionable strategy. Constitutions by design lay down the fundamental principles of a state.

By entrenching such principles in a constitutional text, the idea is to firmly embed them, making them very difficult for any governing body to change for their own advantage. Amendment procedures are therefore vital for the protection of the underlying constitutional principles, and are generally considered to have a somewhat unassailable status. Thus, a government proposed amendment to the constitutional amendment procedure, could in itself be considered an abuse of power.

In this instance the government’s intentions appear to be admirable in the respect that they are seeking to protect minority groups from future abuses, but if the current government can change the constitutional amendment provision with relative ease, what is to stop future governments from doing the same but with less admirable intentions. Hypothetically, a power hungry President could decide to reduce the majority required in Parliament to pass constitutional amendments, which in turn could lead to the easier passage of further amendment bills for means such as increasing presidential powers and removing term limits, seriously threatening existing democratic structures.

The events in Croatia perhaps demonstrate a flaw in the original design of the Croatian constitution. The provision that allows for the supposedly democratic tool, the public initiative, to incite unrestricted constitutional change, seems particularly ill-informed in a country with a substantial Serbian minority group and a history of ethnic tensions. It appears only logical that provisions are put in place to restrict the use of public initiatives and popular votes, with the aim of preventing minority rights abuses resulting from the prejudices of a majority group. What is problematic with this approach is that to enforce such provisions, a change to the constitutional amendment rules is required.

This sets a dangerous standard whereby changing these rules becomes acceptable, and future abuses of this power become possible. To counteract this threat, the government may be wise to consider proposing a second constitutional change, this time setting out strict rules and regulations which restrict the ability of future governments from making any further changes to the amendment rules. To protect both human rights and to safeguard democracy, there may be a need to first change the constitutional amendment procedure, and then take steps to prevent it from being changed again.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the Constitution Unit’s blog on January 24th. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1cNqSLc

—

Christine Stuart is a Research Assistant at the Constitution Unit, University College London

Christine Stuart is a Research Assistant at the Constitution Unit, University College London

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Constitutional amendments by popular initiative: lessons from Croatia’s constitutional outlawing of gay marriage https://t.co/jn00LnFkU4

Constitutional amendments by popular initiative: lessons from Croatia https://t.co/xbRaIQnkSy

Constitutional amendments by popular initiative: lessons from Croatia’s constitutional outlawing of gay marriage https://t.co/VxoU6EccuV

MT @democraticaudit: Constitutional Amendments by Popular Initiative: Lessons from Croatia by Christine Stuart https://t.co/rbZYn71iFP

Constitutional Amendments by Popular Initiative: Lessons from Croatia by the @ConUnit_UCL’s Christine Stuart https://t.co/aLBazFCfYW

#Humanrights Alert

RT @democraticaudit Constitutional Amendments by Popular Initiative: Lessons from Croatia https://t.co/VdZDqs8qIk

#EP2014

Constitutional Amendments by Popular Initiative: Lessons from Croatia https://t.co/fWUPb0SKvC