A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap

It is well known that the number of people neglecting to turn out at elections is on the increase. It is also firmly established that non-voters tend, on the whole, to be younger than the population at large. This non-participation in electoral life increasingly problematic for representative democracy as a whole. In an extract from a new Democratic Audit publication, Guy Lodge, Glenn Gottfried, and Sarah Birch vividly illustrate the growing power gap between young and old.

It is well known that the number of people neglecting to turn out at elections is on the increase. It is also firmly established that non-voters tend, on the whole, to be younger than the population at large. What is less widely appreciated is the growing demographic distinctiveness of non-voters as a group, a distinctiveness that makes their non-participation in electoral life increasingly problematic for representative democracy.

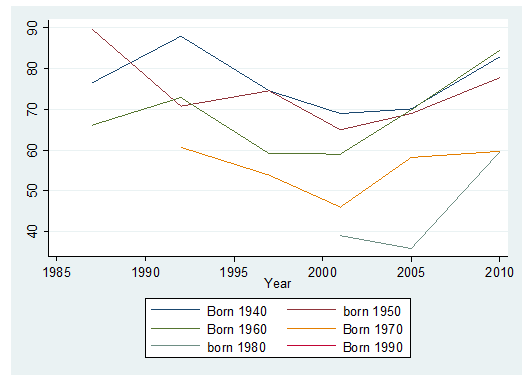

At the 2010 General Election, Ipos-Mori estimated that 76 per cent of those aged 65 years old and over, whereas turnout among the 18-24 age group was only 44 per cent. One might argue that it doesn’t matter too much if young people are less likely to vote, as they will make up for it in their later years. There is little evidence of this overall, however, with turnout exhibiting a downward trend among most age groups, as shown in Figure 1. Moreover, each successive generation starts its voting life at a lower turnout rate than the previous generation (Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley, 2004). This evidence comports with the findings of previous research which has suggested that if citizens fail to vote the first time they are eligible, they are less likely to vote throughout their lives.

Viewed over time, this trend is alarming. In 1970 there was an 18 point turnout gap between 18-24 year olds and those aged over 65; this had more than doubled to over 40 points in 2005. By the 2010 General Election, the turnout rate for an average 70 year old was 36 percentage points higher than that of the typical 20 year old. These worrying trends in turnout inequality show no signs of being reversed.

To add to this are demographic changes which further tilt the democratic process in favour of the grey vote. Craig Berry shows how in the next couple of decades an ageing population will concentrate voting power among those aged over 50: by 2021 the number of potential voters (c. 902,000) for an average single-year cohort size for 50-somethings will dwarf the equivalent number of 18 year olds (c.708,000)

Figure 1: Estimated Turnout Changes by Age Cohort

Sources: British Election Studies and MORI

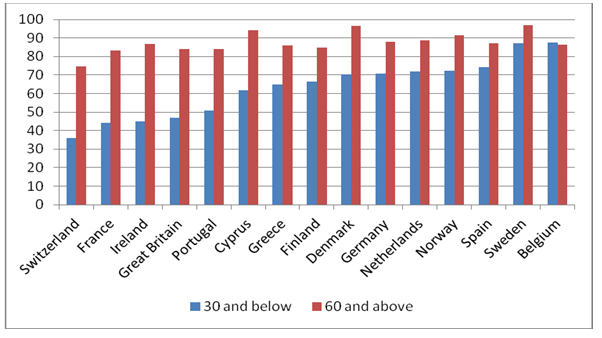

Figure 2 compares voter turnout rates between under-30s and over-60s age groups across several Western European democracies. Though younger people vote in fewer numbers than older people in nearly every country, youth turnout in Britain is comparatively low – only Switzerland, France and Ireland have lower turnout levels. Older voters in Britain turn out at levels more comparable to their European counterparts, however, leading to one of the largest imbalances of voting power between young and old in Europe. The countries which have the least amount of voter inequality between age groups include the Nordic countries, Spain and Belgium (the only country with compulsory voting).

These trends are now clearly established, but what is much less well understood is the extent to which rising political inequality affects the policy outcomes generated by government and the political system more widely. In other words is the political system less responsive to those groups that do not participate than to those that do?

Figure 2: Turnout by country and age groups

Source: European Social Survey (2010 – Wave 5) Note: Question asks “Did you vote at the last national election?”. Does not include those who were ineligible to vote at last election.

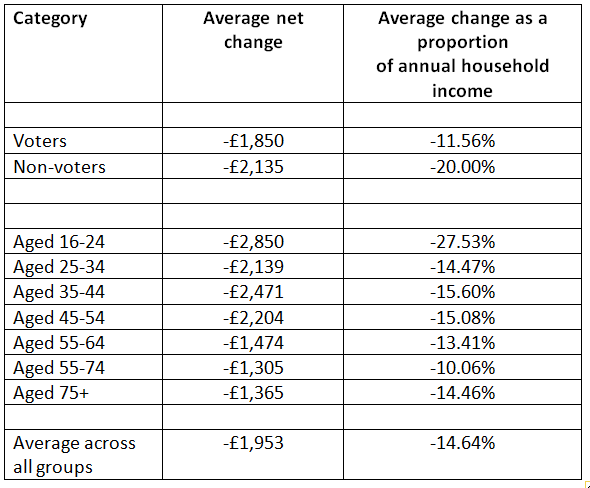

One logical place to look for an effect of this sort is in the Coalition Government’s 2010 Spending Review, which led to dramatic cuts to government spending in most spheres. Though virtually all groups have in some way been affected by the cuts, the argument for a ‘political inequality effect’ would suggest that those groups which participate less ought to be disproportionately affected by the cuts. Table 1 presents the results from a statistical model estimating the impact of the cuts – expressed in real cash terms – on survey respondents to the British Election Study (which allows us to compare the position of those who voted in the 2010 election with those who did not).

The results demonstrate that the average annual loss to voters is £1,850, whereas the average loss to non-voters is £2,135, or 15 per cent more. The difference is even starker when considered in terms of the average household income between groups. The cuts are estimated to represent 11.56 per cent of the annual income of voters, and a full 20 per cent of the income of non-voters. Thus non-voters will be almost twice as badly affected by the provisions of the Spending Review as those who went to the polls in 2010.

When we use the same model to examine the impact of the cuts on different age groups, we see that the cuts consistently hit the young harder than their elders (see Table 1). The 16-24 year old group is suffering particularly from the cuts; people in this cohort face cuts to services worth an estimated 27.53 per cent of their annual household income, whereas no other age group faces average cuts worth more than 16 per cent of their income.

Table 1: Impact of the Spending Review Cuts on Selected Groups

This analysis of the 2010 spending review provides empirical evidence to support the claim that, in this instance at least, the government privileged voters over non-voters. There are, of course, limits to the results from this type of case study analysis. Most obviously it tells us nothing about causality: we know that non-voters got a raw deal from the spending review but we don’t know whether this is because they are non-voters. Doubtless other factors – such as the political values and outlook of the coalition – shaped the decisions. Nonetheless, given everything else we know about contemporary politics, it is reasonable to assume that electoral considerations played some part in the government’s calculations, even if they were not the most salient. Surely it is not just coincidental that the Education Maintenance Allowance for young people was scrapped, while benefits for those over 65 years old – free TV licenses and bus passes, and winter fuel payments – were protected? Or that tuition fees were trebled when pensions were fastened with a triple-lock?

In recent decades political parties and governments have become much more adept at targeting particular voting groups through their communications and policy development. Not surprisingly, they tend to target groups that are most likely to vote. Moreover, for all its faults, recent analysis has demonstrated that the British political system does a reasonably good job of responding to the electorate – that is to voters. In other words, voting matters, and those who do not participate are less likely to get listened to.

This is not to argue that British politics can be said to be characterised by systematic and deliberate discrimination against non-voters. The relationship between electoral participation and political responsiveness is more subtle than this (indeed some decisions may simply reflect an unconscious bias among the political class). Instead, as comparative research suggests, over time, and as a consequence of sustained (self) exclusion from electoral politics, non-voters are under-represented as parties start to form strategies and policies that are biased in favour of those groups with relatively high turn-out rates, and ignore those who are less likely to participate.

Whatever the subtleties of this relationship the consequences for democracy are dire. By tilting politics in favour of high turnout groups, unequal turnout unleashes a vicious cycle of disaffection and under-representation for those groups for whom participation is falling. As policy becomes less responsive to their interests of the young, more and more decide that politics has little to say to them, which further reduces their motivation to vote, which in turn reduces the incentives for politicians to pay attention to them.

This vicious cycle is made more acute by virtue of the fact that different age groups often have divergent policy preferences. This suggests that a strong upward skew in the age profile of voters, such as that observed in the UK, will bias policy in favour of older cohorts. Governments are likely therefore to continue to allocate scare resources to the health service and state pensions, at the expense of investing in policies that favour the young. This point is reflected in a recent IPPR and Policy Network report which found that support for the traditional welfare state consensus was much higher among older voters, whereas support for adopting policies designed to address new social risks, such as childcare provision, was higher among younger voters. The report warned of a danger that growing inequalities in electoral participation might further entrench the welfare status quo and heighten the onset of intergenerational and distributional conflict.

A prolonged era of austerity is likely to exacerbate this situation, leaving politicians more vulnerable to the demands of the retiring baby-boomers, heightening the chances that public policy will become increasingly distorted against the interests of younger people. Last year’s controversy over the so-called Granny tax which asked pensioners, and relatively affluent pensioners at that, to make a relatively small contribution to deficit reduction illustrates how difficult it is for governments to resist the pull of the grey vote. If this is the case it will likely result in more young people turning their backs on the electoral process.

|

Guy Lodge is Associate Director for Politics and Power at IPPR. He leads the institute’s work on political and democratic reform is also the co-editor of Juncture, IPPR’s quarterly politics and ideas journal. |

|

Glenn Gottfried is Quantitative Research Fellow at the IPPR. Before joining IPPR, Glenn taught statistical analysis in politics and European Union governance at the University of Sheffield, where he earned his PhD investigating regional variations in public attitudes towards European integration. He has also received an MA in research methods with distinction, from Sheffield, and a BA in political science from the University of California, Irvine. |

|

Professor Sarah Birch is a Professor of Comparative Politics at Glasgow University. |

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap – https://t.co/xV0xyBK8Q3

If you don’t vote then policy will be biased towards those who do. See our blog and new publication @democraticaudit https://t.co/Q5lMX2r2FI

A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap @democraticaudit @ippr https://t.co/EUKkuZszld

New on DA today: A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap @ippr https://t.co/E26xmVSl82

A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap https://t.co/BDap4e4JNh

“@democraticaudit: A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap https://t.co/gshWYrDCF7” @BiteTheBallot

“@democraticaudit: A vicious cycle of apathy and neglect: young citizens and the power gap https://t.co/HrhzIgfsgZ” A perfect storm!