We should enfranchise young people at 16 while they are still living at home in a settled community

Young voters are less likely to participate in elections than older generations. In this extract from Democratic Audit’s new report, Richard Berry and Patrick Dunleavy show how this is linked to the high levels of mobility among young people above the age of 18, who tend to live in rented accommodation and to move home frequently. One effective way to address the problem, they argue, is to enfranchise young people at an earlier age.

A quarter of 19 year olds have moved between local authority areas in the past year. Credit: Paul Mison (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Young people are the social group least likely to vote, and to be registered to vote. Recent survey evidence shows that 24 per cent of 18-21 year olds are unregistered, and a further 9 per cent are unsure whether they are registered or not – that is, over a third of the youngest voters may not be able to participate in democratic processes. The gap in voting rates between young people and older people in the UK is 38 percentage points – higher than any other advanced democracy.

Age, mobility and voting

The structural reasons behind young people’s low registration and voting levels are numerous and they increase in severity with every passing year. When citizens get the right to vote at 18, they are highly likely to be embarking on a uniquely unsettled period of their life.

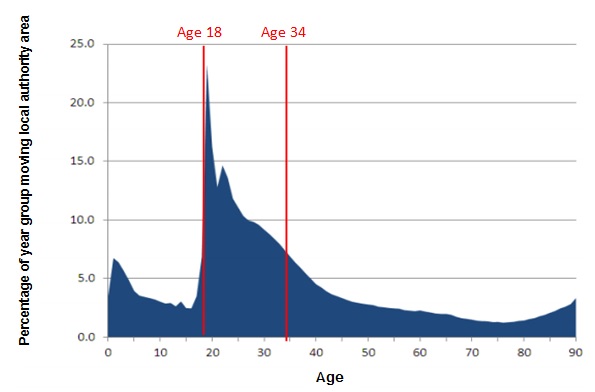

Figure 1 shows that 18-19 is by far the peak age for people moving between local authority areas. In June 2012, 23 per cent of people aged 19 had moved between local council areas within the past year.

Figure 1: The proportion (%) of England and Wales population who moved local authority within the UK during the year ending June 2012, by age group

Source: Office for National Statistics, 2013

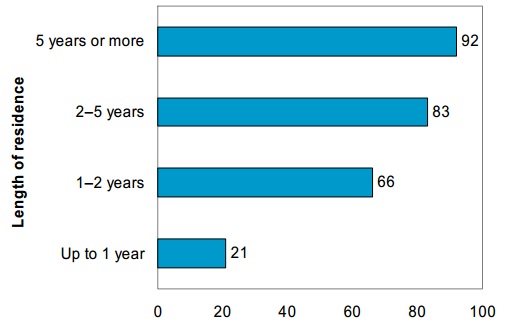

Electoral Commission research has found that while 92 per cent of people who had lived at the same address for five years were registered to vote, only 21 per cent of those who had been there less than a year were registered. Figure 2 provides full details of how longer residence leads to better registrations levels.

Figure 2: The estimated completeness rate of the electoral register by how long citizens have lived at the same residence address

Source: Electoral Commission, 2010. Based on seven case studies.

In the UK people who live in settled communities are more likely to vote and those who have recently moved home are less likely to vote: this factor has an independent impact on turnout when controlling for all other variables. The same effect has also been demonstrated for elections in the United States. Moving between areas would require a young person (who often has never voted before) to register or re-register to vote with a new authority, at the same time as dealing with the multitude of other complications of moving home and living independently.

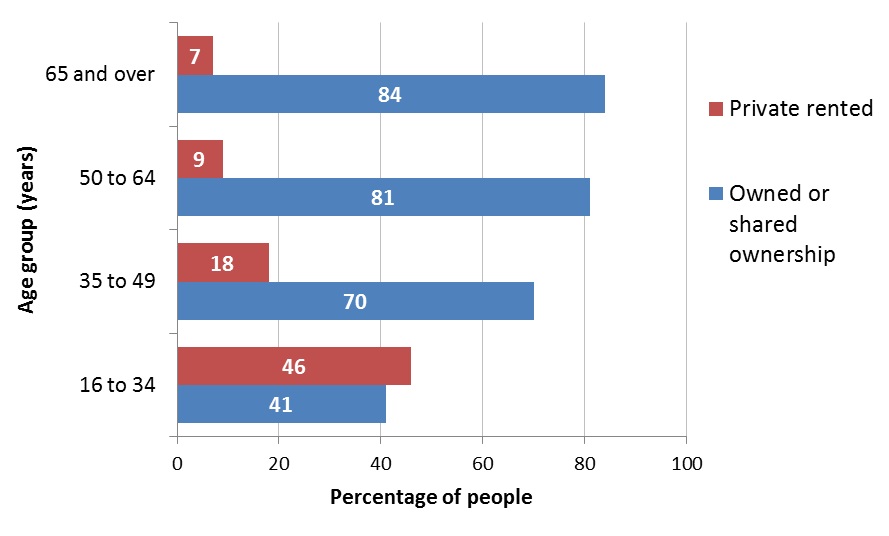

Even after periods like university, where many UK students must move every year of their study time, young people are also much more likely to rent housing in the private sector and to have to move regularly in response to job opportunities – which increasingly reflect ‘portfolio’ career patterns, where people enter the labour market and then may hold a succession of short-period jobs. Figure 3 shows that younger people (aged 16 to 34) have the lowest levels of home ownership and the maximum exposure to private sector renting of any age group.

Figure 3: Housing tenure by age group, 2011

Source: Census 2011 (Office for National Statistics). Social rented and ‘other’ tenures not included.

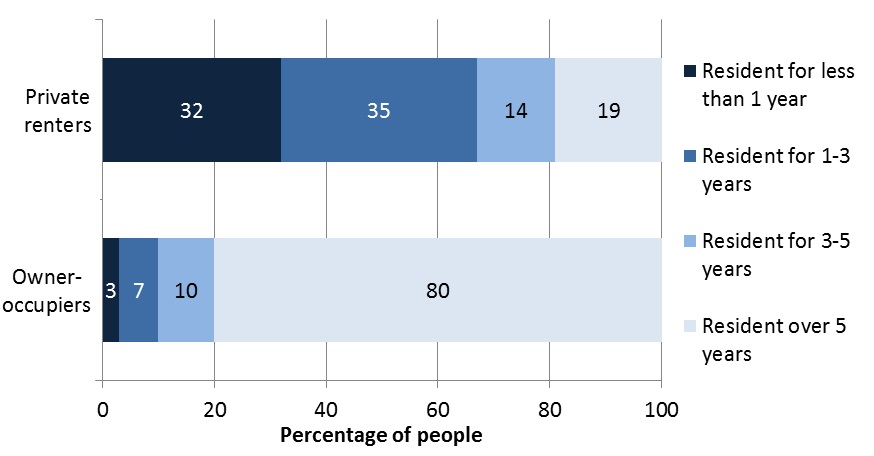

Figure 4 shows recent moves by housing tenure in England. While only one in thirty owner-occupiers has moved in the past year (and one in ten over three years), nearly a third of private renters have moved in the past year (and two thirds have moved in the past three years). Hence it is unsurprising that research shows that people who live in rented accommodation are less likely to be registered or to vote. According to Electoral Commission research, while about 90 per cent of owner-occupiers are registered to vote, only 44 per cent of those renting privately are registered (all ages).

Figure 4: Length of residence by tenure, 2011-12

Source: English Housing Survey 2011-12 (Department for Communities and Local Government)

Lowering the voting age

Voting is a critically important habit for citizens to develop in a democracy, and patterns of participation are established early in people’s voting lives. Research by both Elias Dinas and by Mark Franklin has shown that if voters vote in the first elections they are eligible for, they are more likely to vote throughout their lives, and vice versa. The evidence presented above on the life circumstances of young people establishes a strong case for lowering the voting age to 16.

Nearly nine in ten 16-19 year olds live with their parents. Votes at 16 would allow young people to vote at an age when the vast majority of them are living in a stable environment: that is, with parents and in a community that they are long resident in, where they go to school and have many peers with whom they share local information and insights.

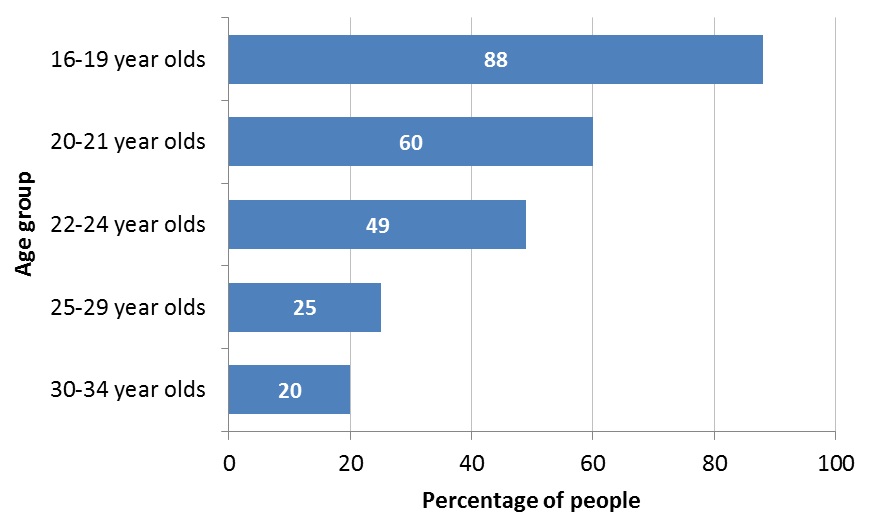

Although there has been a recent increase in adults living with parents across age groups, it is clear that only the youngest adults live predominantly with their parents. Figure 5 shows this in more detail. One US study of under-25 year olds showed that turnout among those who were still living with parents was nine percentage points higher than among those who had left home.

Figure 5: Proportion of people living with parents by age group, 2008

Source: Stone, Berrington and Falkingham 2011

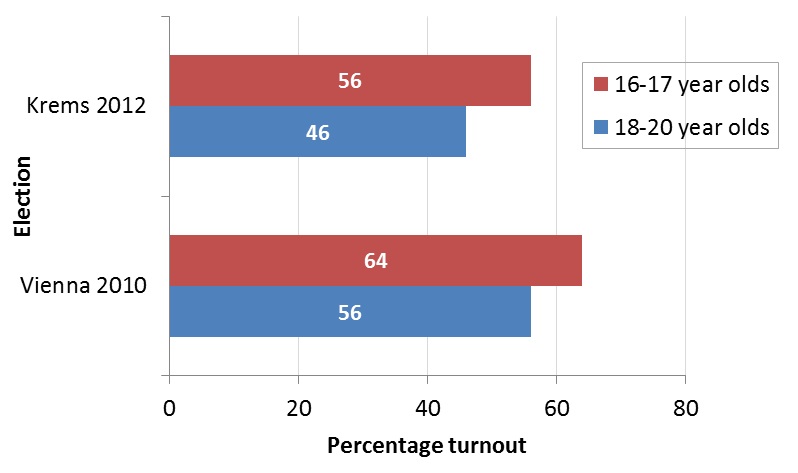

The Austrian experience – as discussed on Democratic Audit recently – demonstrates the positive impact of lowering the voting age to 16. Austria is so far the only European country to have done this for nationwide elections. Evidence indicates that first-time voters aged 16 and 17 were more likely to vote than first-time voters at older ages. After the voting age was lowered, turnout was 8-10 percentage points higher among 16-17 year first-time voters in regional elections than it was among older first-time voters. Figure 6 demonstrates this for elections in two regions (Vienna in 2010 and Krems in 2012).

Figure 6: Electoral turnout among first-time voters in Austrian regional elections

Source: Zeglovits and Aichholzer, 2014

—

The authors are grateful to Steve Akehurst of Shelter for help in sourcing data for this post.

This post is an edited extract from Democratic Audit’s new report, Engaging young voters with enhanced election information, based on our submission to the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee inquiry into voter engagement.

Note: This post represents the views of the authors, and does not necessarily give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before commenting. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/PiYxUN

—

Richard Berry is managing editor and researcher at Democratic Audit. His background is in public policy and political research, particularly in relation to local government. In previous roles Richard has worked for the London Assembly, JMC Partners and Ann Coffey MP. He is the author of the book Independent: The Rise of the Non-Aligned Politician (Imprint Academic, 2008). He tweets at @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is managing editor and researcher at Democratic Audit. His background is in public policy and political research, particularly in relation to local government. In previous roles Richard has worked for the London Assembly, JMC Partners and Ann Coffey MP. He is the author of the book Independent: The Rise of the Non-Aligned Politician (Imprint Academic, 2008). He tweets at @richard3berry.

Patrick Dunleavy is the Co-Director of Democratic Audit, and Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics (LSE). Patrick joined the LSE in 1989, and founded the Public Policy Group in 1992. He has published widely in a number of areas, including electoral systems and digital government. His most recent books are The Impact of Social Science (SAGE, 2014, with Jane Tinkler and Simon Bastow) and Growing the Productivity of Government Services (Edward Elgar, 2013, with Leandro Carrera). He tweets at @PJDunleavy.

Patrick Dunleavy is the Co-Director of Democratic Audit, and Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics (LSE). Patrick joined the LSE in 1989, and founded the Public Policy Group in 1992. He has published widely in a number of areas, including electoral systems and digital government. His most recent books are The Impact of Social Science (SAGE, 2014, with Jane Tinkler and Simon Bastow) and Growing the Productivity of Government Services (Edward Elgar, 2013, with Leandro Carrera). He tweets at @PJDunleavy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Only a fifth of people who moved home in past year are registered to vote – much more likely to be young people https://t.co/koexAeGOLS

We should enfranchise young people (in UK) at 16 while they still live at home argue @PJDunleavy & Richard Berry: https://t.co/4VdV8hAvoS

A quarter of 19 year olds moved between council areas in past year – bad time to expect this group to start voting https://t.co/xLRjbwZAy1

We should enfranchise young people at 16 while they are still living at home in a settled community https://t.co/ck72fcXGym

Thanks to @Shelter for support with data for our new post on young people people, mobility and election turnout https://t.co/XNsZRE884l

Building the case for @votesat16… high geographical mobility post-18 means this is wrong age to enfranchise people https://t.co/Kyu2orZQPA

We should enfranchise young people at 16 while they are still living at home in a settled community https://t.co/CbFHeAszPW