Book Review: At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron

Special Advisers and prime-ministerial aides have come to prominence increasingly over the last decade, with operatives like Alastair Campbell and Andy Coulson frequently making front-page news. But little is generally known about the role itself, what it entails, and how it has developed down the years. Catherine Haddon, in reviewing this new offering from Andrew Blick and George Jones, finds their history of the role enlightening and impressive in its breadth and scope.

‘The office of Prime Minister is occupied by one individual but the exercise of the role has always been a group activity’.

With this theme at the heart, Andrew Blick and George Jones’ latest book moves on from their previous study of prime ministers to look at the advisers that surround them. Blick and Jones take us all the way back to Robert Walpole to examine how the support of aides and the reaction to them helped define not only the concept of permanent Civil Service but also the very role of Prime Minister itself.

What Blick and Jones’ book demonstrates is that the UK premiership has not been a static organisation – it has adapted to the style and approach of the individuals that held the post. Likewise the support around them has tended to be less about wiring diagrams and more about getting the right personalities. At the same time, those around a PM have usually played a big role in how the rest of government viewed the premier.

The story of prime ministerial aides raise lots of questions, some of which Blick and Jones consciously seek to explore, some which are left hanging. We see the problems of patronage and political factions – and not just in the earlier period. They raise questions about the burden of work facing prime ministers and how that changed according to the scale of policy and monetary dealings for which government was responsible.

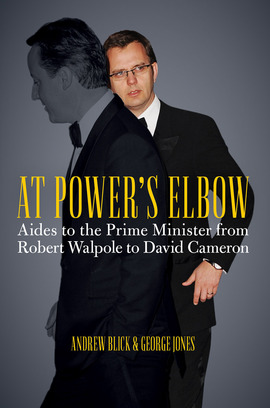

At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron. Andrew Blick and George Jones. Biteback Publishing. September 2013.

Some of this history shows long-term evolution. The book is an excellent reminder of how in an earlier age and up to the nineteenth century departments – the Treasury particularly and more widely the Civil Service as a whole – evolved in order to be a permanent support to ministers and the Prime Minister in particular. And as prime ministers’ evolved from fully functioning First Lords of the Treasury, over the course of 19th Century, to become ‘without portfolio’, so their aides also changed function. Alongside the evolution is continuity though. Aides continued to reflect the individual prime ministerial style: for Gladstone they helped generate sufficient employment to keep that workaholic Prime Minister busy; for Disraeli they helped relieve the burden.

In the nineteenth century the preference for smaller No.10 rather than a full department was laid: ‘a full department was less suited to operating in the delicate fashion that was often crucial to the exercise of prime ministerial power’. By the early twentieth century, under Lloyd George, as the role of the Prime Minister expanded yet again, so did the need for support.

So why did this expansion not see a more permanent department around the Prime Minister? The answer lies with another continuous characteristic of Prime Ministerial support: ‘After [Lloyd George] fell from power in 1922 his successors sought to distance themselves from his approach’. Successive prime ministers have tended to react to how their predecessors operated, particularly when it had been a cause for criticism. It happened to Robert Walpole, to Lloyd George, and again with reactions to Tony Blair’s No.10. This in turn affected discussion of what support there should be. Newspaper articles in the 1920s criticising the idea of a fully-fledged ‘Department of the Prime Minister’ bear striking resemblance to that debate today.

Lloyd George’s premiership also raises other questions which the book is less able to answer, particularly the effectiveness of these aides. In 1916 Lloyd George brought about big changes to address the failings he, and others, perceived in the Asquith mode and which were blamed for poor handling of the First World War. Lloyd George’s reforms – creating a de facto policy unit and the cabinet secretariat – were about the need to ‘provide a lead himself or to force Cabinet members to take decisions over urgent issues’. Here the authors get to the cusp of asking whether Asquith’s minimal support mechanisms (as opposed to Lloyd George’s) was a factor in the ‘perception that he [Asquith] provided weak leadership during the First World War’, a question which is unfortunately left hanging.

The book greatly benefits from the considerable period over which the authors have been studying this topic. Interviews from three decades ago complement the limited published or unpublished accounts of the men of these earlier eras, the memoirs of more recent past and (until the Cabinet Secretariat) the just as limited official records. As such, the book provides a good overview of many of the most interesting or most prominent aides – character sketches largely. Biographically, one is sometimes left wanting more. In the case of the earlier periods, the reason is clear, sources of information of these men – and it is largely men – are few and far between. By the time one gets to William Gladstone the detail picks up; his diaries reveal much more about those around him than predecessors.

The book is a tour through various aides to PMs over a considerable period and valuable for that. It leaves hanging many questions about just how much these different roles have in common, except their proximity to the Prime Minister. Cabinet secretaries are highlighted alongside press chiefs, chiefs of staff and occasionally unofficial advisers – in earlier years this blurring of distinction is apt, the roles were blurred; for more recent years the reasons for choosing some advisers and not others feels a little less clear. And for the most recent period, there is little that is new here.

The authors do draw some conclusions about the support that prime ministers’ look for: bureaucratic support – both secretarial and in managing or navigating the machine, policy advice and expertise, political and patronage support, and personal (it can be a lonely job!).

Overall, the book is most useful for the breadth of perspective it provides. It reminds us that the Prime Minister combines the personal and the professional. For Churchill, ‘the boundary between professional and personal life was unclear. Work did not end and he expected his staff to take a similar attitude and be available for him at all times… [even] from the bath or his bed.’ Yet the purpose of the job is ultimately a professional one, to ensure the will of the prime minister is brought to bear. And in thinking how they can best do that, any aspiring prime ministerial aide could do worse than read this book.

——-

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. It originally appeared on the LSE Review of Books. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1nmHNHx

—

Catherine Haddon is a fellow at the Institute for Government. She joined the Institute in November 2008 from academia. She leads the Institute’s work on the history of Whitehall and reform and on managing changes of government.

Catherine Haddon is a fellow at the Institute for Government. She joined the Institute in November 2008 from academia. She leads the Institute’s work on the history of Whitehall and reform and on managing changes of government.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

low aqua 11s

delivery services in your town.

jordan 11 concord low

https://www.jordan11lowconcord.com pre order jordan low concords

air Jordan 12 for sale

attendants meaning that convention 2013 will be the largest,

buy jordans

If you do all your maintenance yourself except for warranty work, you will know it’s always Done

sac hermes

I always spent my half an hour to read this weblog’s content all the time along with a cup of coffee.|

Book Review: At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron https://t.co/SEyASHqorD

@democraticaudit @pjdunleavy At Power’s Elbow is an interesting book showing importance of advisors to PMs; co-authored by Prof George Jones

Book Review: At Power’s Elbow: Aides to the Prime Minister from Robert Walpole to David Cameron https://t.co/9FayWzHcE6