16 and 17 year olds are not fully autonomous, and therefore should not be allowed to vote

The Scottish Government has allowed 16 and 17 year olds to participate in the forthcoming referendum on independence. Here, Dan Degerman argues that this age group, though in some ways in possession of the necessary faculties and experiences required to participate in the electoral process, lack the right to vote due to their restricted options in other spheres of life.

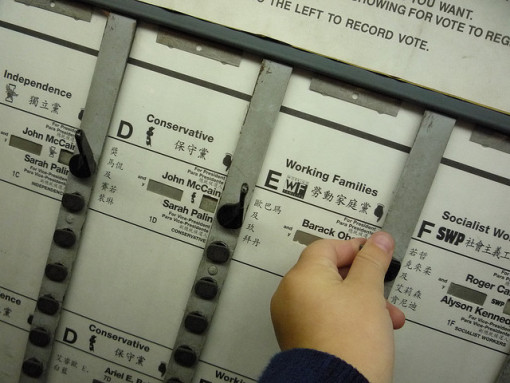

A child voting on behalf of their parent (Credit: Bryan Bald, CC BY SA 2.0)

In September of this year, the Scottish people will take a decision regarding the future of their nation and its relationship with the rest of the United Kingdom. While nationalists and unionists are currently entangled in a fierce battle for their desired result, until recently, the shape of the electorate itself was a key point in the debate.

The question of who should be allowed to vote in a democratic referendum may seem anachronistic to citizens of a society where seemingly everyone, regardless of sex, race or class has equal political say. Closer scrutiny, however, reveals that the UK denies some of its citizens right to formal participation. The voting rights of individuals with mental disorders are constrained, and incarcerated convicts are denied the right completely. Significantly, individuals under the age of 18 are systematically disenfranchised.

The basis of this practice is the supposition that minors lack the somewhat opaque capacities necessary to manage the complexities of democratic participation. The generally accepted purpose of voting in democratic referenda is to legitimize governmental power. By authorizing a government through the electoral process, citizens express their consent to its power. Legitimate consent, however, can only be given by self-governing individuals. Thus, put differently, the consensus has been that minors lack the autonomy requisite to be able to grant legitimate political consent.

In the autumn of 2013, parliament passed into law the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act 2013, which lowered the age of electoral majority for the referendum to 16, potentially setting precedence for decreasing the voting age in future elections. Some of the voices in favour of this reform argued that it was justified because it would raise voter participation. Obviously increasing the size of the electorate is certain to raise absolute participation numbers. Yet, this fact is irrelevant because it fails to demonstrate that adolescents have a right to vote. Others attempted to assert this right. Youth interest groups have argued that since 16 year-olds are allowed to express consent in some situations, such as sexual relations, they should be permitted to consent in political elections as well. It should hardly be necessary –although it evidently is – to point out that ability in one sphere of social life need not imply any rights in another.

The stronger arguments for voting-age reform relies on scientific evidence. There is some neuroscientific research which suggests that by the time adolescents are 16, their brain is sufficiently developed to support adult-like reasoning capabilities. Such arguments reflect the growing importance of neuroscience in the political and legal discourse. However, they fail to prove that adolescents are autonomous. Coarse neurobiological maturity demonstrates only that adolescents have the potential to become – not that they are – autonomous.

Autonomy is itself is difficult to define. However, scholars generally agree that self-rule requires both positive capacities, such as particular cognitive capabilities; and negative freedoms, such as freedom from coercion. Beyond this there is little consensus. However, since we are interested in a specifically democratic form of autonomy, we can turn to actual democratic and legal conventions for two minimal criteria with which a useful conception of autonomy must correspond: 1) Democratic sensibilities demand that a majority of persons in a society either do or can reach the threshold necessary for democratic participation. 2) Legal and cultural praxes suggest that autonomy is not an all-or-nothing matter, but that it may obtain in different degrees. For example, in Scotland, a child under 12 cannot be prosecuted for a criminal offence; the drinking age is 18; and the age of sexual consent is 16.

To consider whether adolescents should have the right to vote, we must find a construct of autonomy that conforms to these criteria. Given the aforementioned proliferation of neuroscience in politics, it would also be preferable if it were compatible with scientific evidence. One construct that appears to rise to the challenge is the self-maintenance model of autonomy, developed by Professor Alvaro Moreno Bergareche and colleagues at the University of the Basque Country.

In this view, autonomy is the adaptive self-maintenance of identity through interaction with the environment. A person’s engagement with the environment generates an increasing number of physical and mental constraints, such as abilities, desires, values and beliefs. Identity is the totality of these constraints at a given point in a person’s life. As someone engages with their environment, they simultaneously change their environment. Consequently, the feedback from the environment to the person changes, which engenders new constraints or alters old ones by strengthening or weakening them, leading to yet more changes in the environment. A more complex system, with a large number of strong constraints, will be a more autonomous system, since any single action will have less of an impact on the identity of the system. Complexity, in effect, makes it easier to self-maintain identity.

This conception acknowledges that humans are intrinsically social beings that exist in the context of intricate cultural structures. These structures demand complex, extrinsic behaviour of the humans within them in exchange for protection and care they provide. We become autonomous within these societies through social interactions with other humans and in relation to the social responsibilities we have. Therefore, any questions regarding particular thresholds of autonomy, such as voting age, must be answered in the context of a given society.

In light of this construct, in evaluating whether people are autonomous, we must take into account three factors: biological maturity, social interaction and time. It may be the case that the neurobiological maturity of the average 16-year old is identical to that of an 18-year old. However, a 16-year-old lacks access to a range of important opportunities for social interactions that an 18-year-old has. For example, particular levels of schooling or work experience, legal ownership of particular items, the right to drink, the right to drive, and parental emancipation. Let us call such items technologies of autonomy: social artefacts that enable individuals to generate new and culturally particular constraints and to effectively maintain and develop an identity within their environment. Since adolescents are denied access to the social resources that might permit their biological potential to germinate, they cannot be autonomous. Therefore, they do not have a right to vote.

The British 19th century legal scholar, James Fitzjames Stephen once wrote that “power precedes liberty.” Rights, as he saw it, were only useful insofar as people had the capability to exercise them effectively. This seems to hold true for the right to vote as well. The act of voting is meaningless unless it is carried out by individuals who have the power to govern their own actions. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the government to empower voters to render decisions that are in the voters’ own interest. However, in the contemporary British discourse, this responsibility seems to have been replaced by a focus on granting people rights that they have not been taught how to use.

—

Note: this piece represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1l6Jp7R

—

Dan Degerman is a master’s student in political and legal theory and a 50th Anniversary Scholar at the University of York. In 2011-2012, he was a Researcher-in-Residence at the Center for Neurotechnology Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies in Arlington, Virginia, where he explored the ethical, legal and social implications of human enhancement. Currently, he is working on a dissertation that investigates the depolicization of mental depression in the United States.

Dan Degerman is a master’s student in political and legal theory and a 50th Anniversary Scholar at the University of York. In 2011-2012, he was a Researcher-in-Residence at the Center for Neurotechnology Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies in Arlington, Virginia, where he explored the ethical, legal and social implications of human enhancement. Currently, he is working on a dissertation that investigates the depolicization of mental depression in the United States.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

16 and 17 year olds are not fully autonomous, and therefore should not be allowed to vote argues Dan Degerman https://t.co/KK0mXElGyW

16 and 17 year olds are not fully autonomous, and therefore should not be allowed to vote says Dan Degerman https://t.co/v5PfmxU22F

@ddegerman argues limited youth autonomy means voting age can not be lowered https://t.co/lfcGHR8Sw3 @HansardSociety @votesat16 @OfficialSYP

@ddegerman argues limited youth autonomy means voting age can not be lowered @JonTonge @PoliBlogManc @philipjcowley https://t.co/lfcGHR8Sw3

16 and 17 year olds are not fully autonomous, and therefore should not be allowed to vote https://t.co/ag8rHqXSaE