Motions of no confidence can negatively impact upon the public’s view of the Government

Motions of no confidence are used sparingly in the UK, with their use tending to be reserved for moments of acute political crisis for the Government, such as the resignation of Margaret Thatcher or the collapse of a cross-party agreement. Here, Laron K. Williams and Zeynep Somer-Topcu draw on research from a recent article they co-published in the European Journal of Political Research to show that while their practical use is primarily to bring about elections and topple Governments, they also influence how the public see the Government in question, and can be used by opposition parties to this end.

In November 2013, the leader of Syriza, Alexis Tsipras, was given the perfect opportunity to publicly criticise the coalition government’s austerity attempts by proposing a no-confidence motion (NCM). “You have destroyed society and society will no longer allow you to continue this destruction”, Tsipras declared, stating that austerity policies have triggered a “social holocaust” (New York Times, 11 November 2013). Although supported by some other opposition parties in the parliament including the Communist Party and Golden Dawn, the motion failed to achieve the needed 151 votes. Its failure, however, was not a surprise as even Syriza did not quite expect it to pass.

In addition to testing the strength of the governing coalition, the NCM fulfilled a second motivation—heightening the public’s awareness of the coalition’s policies by criticising the government for increasing taxes on the poor and using those taxes to protect the rich (The Guardian, 11 November 2013).

While those NCMs that pass understandably receive the most attention, opposition parties often propose NCMs to weaken the governing parties’ images. After all, only a small number of NCMs achieve the necessary votes to force the governments to resign or to call for new parliamentary elections. Instead, opposition parties may use NCMs, for instance, to highlight the government’s responsibility for a specific salient policy. The Liberals’ NCM against Joe Clark’s Conservative Canadian government in 1979 concerning high energy prices was a good example (Globe and Mail 1979). Opposition may also challenge the government with an NCM to try to elevate a salient issue on the political agenda.

This was the intention for the NCM against Finland’s ‘rainbow coalition’ in March 1998. The centrist opposition used the opportunity to highlight the plight of Finnish farmers in the face of EU policy (Agence France Presse, 1998). In addition, NCMs are often highly publicized opportunities for the opposition party to publicly question the government’s ability or competence. Even NCMs with little chance of success receive front-page coverage. When the British Labour Party proposed an NCM in 1991 over the Conservative Party’s decision not to abolish the poll tax, it triggered a ‘bitter and rowdy debate that ended in uproar’ (Press Association, 1991). The circumstances of the debate and the positions taken by the parties were widely reported in British newspapers such as the Guardian and the Independent.

As these examples show, opposition parties often skillfully use NCMs to hurt governing parties’ competence evaluations by voters. And, we know from widespread anecdotal and empirical evidence that citizens’ evaluations of parties have substantial influence over the parties’ prospects for electoral success (Clark 2009, Clarke et al. 2009). Indeed, merely proposing NCMs provides the opposition party that proposed it a meaningful gain at the next election, often at the expense of the governing parties (Williams 2011). What we do not know is, on the other hand, whether political parties use these NCMs and the critical environment they create to strategize about their policy positions for electoral gains.

Political parties are motivated about winning votes and gaining office, a desire that partially drives both their overall left-right positions and positions on particular issues. How they change their positions, on the other hand, depends on the information they receive about what will work and fail.

In the presence of an NCM, where the governing parties are attacked for their policy positions, opposition parties should, then, strategically change their positions with respect to the government in order to successfully compete for the votes that the governing parties are losing as a result of the NCM. We show in our forthcoming paper that opposition parties move their positions away from the government’s position in order to disassociate themselves from the failing government. This effect is especially pronounced when there are additional negative signals about government performance.

After all, NCMs are targeted attacks by opposition parties. Even though they require a considerable amount of prior organisation and may backfire against the proposer, they are proposed for the purpose of criticising governments. As a result, we argue that both voters and political parties are more attentive to NCMs when there are reinforcing negative signals about the government’s performance, such as weak economic performance or scandals. More simply, NCMs will matter more when they are coupled with poor policy performance.

We test these expectations on a sample of 19 advanced democracies from 1970 to 2007 using left-right positions derived from election manifestos in combination with NCM and economic growth data.

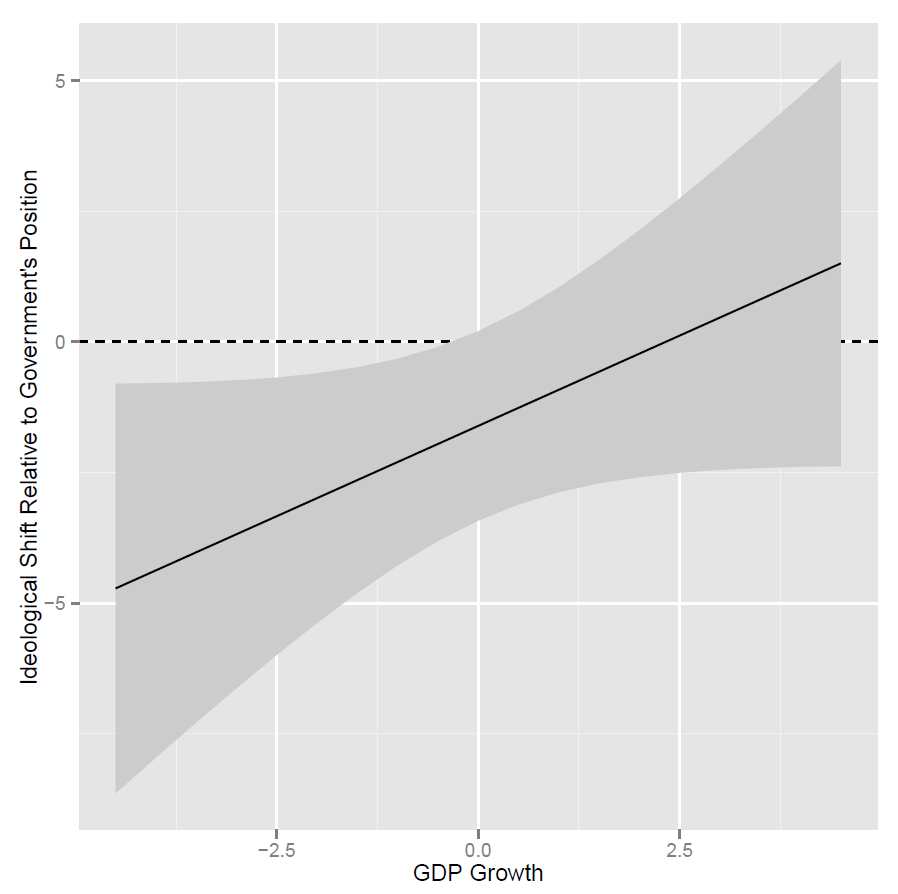

Figure 1 shows our main finding. In this graph, the solid line represents the influence of an NCM on opposition parties’ shifts either toward (positive values) or away from (negative values) the government’s left-right position, across different values of economic growth (x-axis). The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. These results indicate that when economic growth is negative an NCM encourages opposition parties to distinguish their own positions from those of the government by shifting away from their position. Recall that our theory applies to more than just economic performance, but to poor policy performance in general. Indeed, we also find that other indicators—such as scandals and international conflicts—magnify the “push” that NCMs exert on opposition parties’ positions.

Figure 1: Marginal Effect of a No-Confidence Motion across Economic Growth (Main Model)

How does this theory apply to actual policy shifts? An illustrative example for our results comes from Denmark. Throughout 1974, Poul Hartling’s Liberal Democratic Party minority government in Denmark had relied on intense negotiations with multiple opposition parties in order to remain in office. As economic growth declined and inflation increased, the opposition increased its criticism of the government. At this time, the Communist Party reacted to the government’s proposed budgetary cutbacks and income tax relief with an NCM which was supported by the Progress Party.

The NCM was narrowly defeated, but it demonstrated to the public that the minority government would be unable to implement the party’s economic priorities (i.e., reducing inflation, strengthening the kroner, providing income tax relief, etc.) with the current Folketing membership. Hartling subsequently recommended parliamentary dissolution and new election. Upon closer examination, we can see that the combination of negative economic growth (real GDP per capita growth rate of -2.33% according to the Penn World Table), and a highly-publicized NCM illustrating salient problems (balance of payments issues), provided the incentives for ideological shifts.

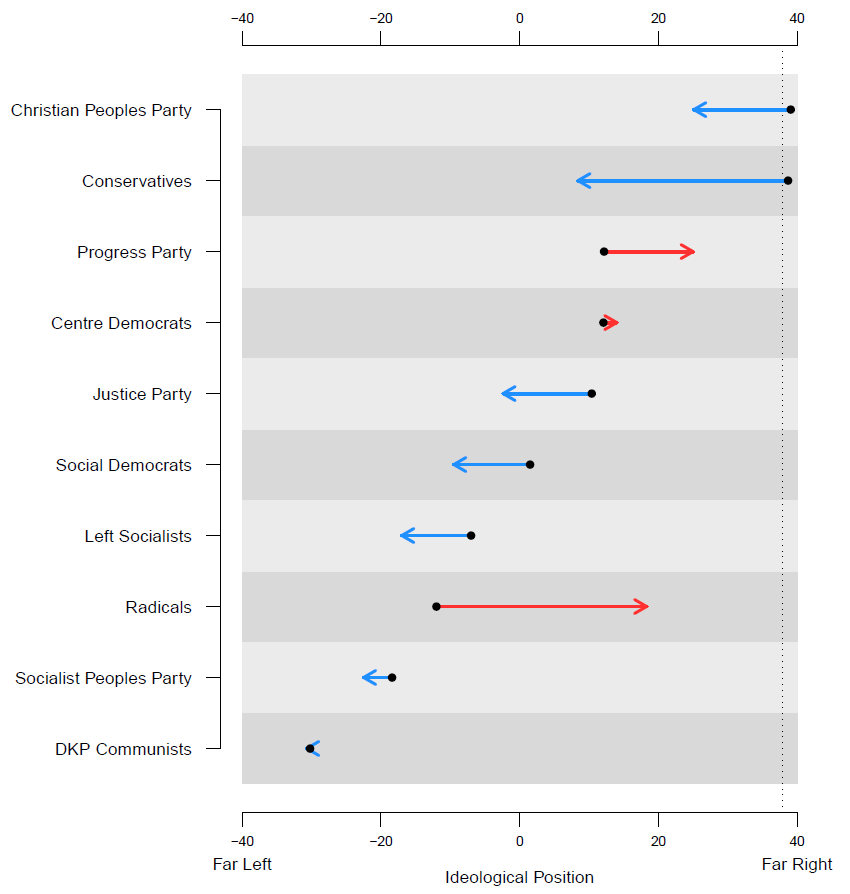

Figure 2 shows the left-right ideological change of each opposition party holding seats in the Folketing from the election on December 4, 1973 to the election on January 9, 1975. The figure shows the partisan positions established by these parties for the 1973 election (represented as a black dot), as well as the ideological change at the next election (indicated by the direction and length of the arrow, with blue arrows indicating those parties that moved toward the government).

As a reference, we also provide a vertical dotted line to show the government’s (i.e., Liberal Party’s) ideological position in 1973. Of the 10 opposition parties in the Folketing, seven moved leftward and further away from the government’s position. The magnitude of these shifts is quite large, as six of the seven parties moved more than 10 points away from their original position. These shifts are consistent with our theoretical expectations that opposition parties move away from a government challenged by a NCM that also experiences poor economic performance.

Figure 2: Illustrative Example of the Effects of No-Confidence Motions on Ideological Change across Two Danish Elections: December 4, 1973 and January 9, 1975

Note: This figure shows the movement of each Danish party on the left-right scale (ranging from -40 for far left to +40 for far right) from December 4, 1973 to January 9, 1975. The dashed line indicates the government’s position in the 1973 election.

To sum up, our current research indicates that NCMs are not only tools for opposition to topple governments and call for early elections. They can help negatively affect public opinion about governments, and through that, they can assist opposition parties in their search for an electorally-advantageous policy position.

—

To see the journal article on which this post is based, please click here.

Note: this post represents the views of the authors, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1tqSdXL

—

Laron K. Williams is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri.

Laron K. Williams is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri.

Zeynep Somer-Topcu is Assistant Professor at the Max Kade Center for European and German Studies at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Zeynep Somer-Topcu is Assistant Professor at the Max Kade Center for European and German Studies at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

No, really? Voters percieve govts more negatively after a vote of no confidence https://t.co/tdmuYblWl6 @democraticaudit

How does the public react when governments receive a vote of no confidence? https://t.co/mfZgoamyrm

Motions of no confidence can negatively impact upon the public’s view of the Government https://t.co/e3N7TZOHAS

Motions of no confidence can negatively impact upon the public’s view of the Government https://t.co/m9vbtIqUCb