What the independence referendums in Québec suggest about Scotland

The current dynamics of the debate in Scotland recalls very much what Québec experienced in its referendums of 1980 and 1995, writes André Lecours. While there are striking similarities, such as the bulk of the argument against independence resting on the potential economic and financial implications of secession, there are also important differences, such as the absence of any debate about the majority required to trigger the process of secession. The Québec experience also suggests, among other things, that the SNP is unlikely to be tarnished in a post-‘no’ Scotland, and that the debate on independence is certainly not closed.

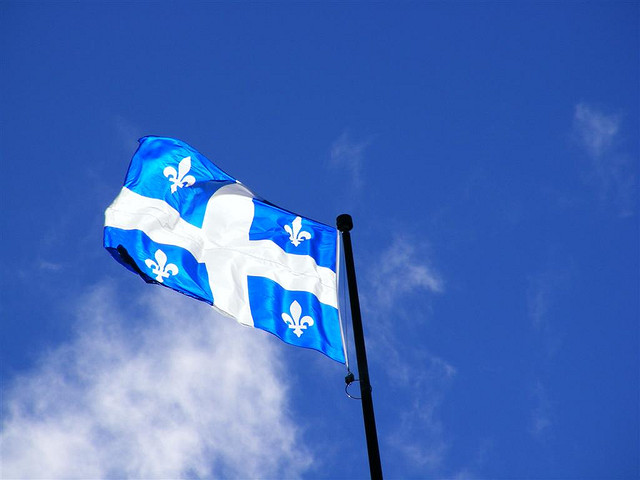

Independence referendums are rare in liberal-democracies so there are few comparable instances to the forthcoming Scottish referendum. The main comparable case is Québec, which has experienced two popular consultations (in 1980 and 1995) on the question of independence. There are both similaritiesand differences between the Scottish and Québécois referendums.

At the broadest level, the current dynamics of the debate in Scotland recalls very much what Québec experienced in 1980 and 1995. The ‘yes’ side in Scotland is making the pitch that things will be better after independence, specifically that Scotland can be fairer and more progressive once freed from a more conservative England. Similar arguments were heard in Québec, in relation to the rest of Canada, during the referendum campaigns. In Scotland, the ‘yes side’ has also mobilized large segments of civil society and, in a sense, made independence ‘cool.’ In Québec, the referendums were similarly dynamic, and indeed polarizing, events where supporters of independence were more vocal and more visible than their opponents.

As was the case in Québec, the bulk of the argument against independence rests on the potential economic and financial implications of secession. The PQ was always on the defensive on these issues, and its case that Québec would come out financially unharmed, or even improved, from secession never convinced a majority of Quebeckers. In this sense, it seems that fears about the economic and financial consequences of secession ultimately played a more important role than attachment to Canada per se in a majority of Quebeckers deciding against independence both times. Scots are similarly hearing about the potential negative financial, fiscal and economic outlook of an independent Scotland. It remains to be seen how this factors into their decision.

There are also important differences between the Québec and Scottish experiences. The most striking difference is the negotiated agreement between the Scottish and UK governments on the parameters of the referendum. This is something that the secessionist Parti Québécois (PQ), as well as the ‘federalist’ (supporter of the on-going presence of Québec in the Canadian federation) Liberal Party of Québec, never accepted. Indeed, for the PQ (and the Liberals), the responsibility to specify the rules and process of a referendum lies with the Québec National Assembly alone and does not involve the Government of Canada. The federal nature of Canada, involving the division of sovereignty since its creation, most likely shaped this conception, which was not challenged by the Government of Canada until a few years after the 1995 referendum when it decided to legislate on the role of Canada’s House of Commons in any future referendum on independence (the so-called Clarity Act).

A second important difference is that the question is, on the surface, crystal clear. The Québec questions were about ill-defined concepts (sovereignty-association, sovereignty-partnership). The 1995 question was criticized for being long and confusing. This being said, the Scottish campaign shows that even a seemingly clear question can involve lots of ambiguity. The very meaning of independence necessarily becomes the centre of a political argument during such campaigns, with supporters of the ‘yes’ side presenting a ‘soft’ version of its nature while the ‘no’ side works with a ‘hard’ view of what it involves.

A third difference, especially remarkable from a Canadian perspective, is the absence of any debate about the majority required to trigger the process of secession. In Canada, some federalists (not all) argued that the decision to break-up a country warranted some type of supra-majority. All Québec political parties insisted that 50% + 1 was a well-established threshold in a democracy, and that all suggestions for the need of a greater majority was simply hidden partisanship. After the close result of the 1995 referendum, the Government of Canada’s independence referendum legislation stipulated that the result needed to be ‘clear,’ which has widely been interpreted as involving something more than a simple majority. In the case of Scotland, the events from the 1979 referendum obviously made the argument for any supra-majority requirement nearly impossible to sell.

Finally, a Canadian observer can not help notice the seemingly important presence of the UK government in the debate. Although Prime Minister David Cameron himself has been discrete, UK departments have produced studies that have shaped the debate. This stands in sharp contrast to the 1995 Québec referendum where the Government of Canada was barely visible until the very last weeks of the campaign. With the ‘no’ side leading in the polls early on in 1995, federal officials decided to have the Government of Canada stay mostly out of the campaign for fear that important involvement could result, the thinking went,in more Quebeckers voting ‘yes’ because they would want to show they were not ‘intimidated’ by critics of independence.

What does the Québec experience suggest about a post-‘no’ Scotland, if this were to happen? The first insight here is that a ‘no’ vote does not close the debate on independence. Another referendum is a possibility. This will be more difficult in Scotland than it was in Québec because majority governments are less likely in Scotland as a result of the electoral system. However, if a crisis emphasizing the Scottish-English cleavage were to develop (for example, the UK withdrawing from the EU), an SNP-led government could organize a second referendum. The second insight is that the SNP is unlikely to be tarnished by a ‘no’ vote. Quebeckers re-elected PQ governments after both of its referendum losses.

The very close 1995 results in Québec did not yield any important constitutional and institutional change. Here, I think the Scottish scenario will play out differently, all major parties having committed to further devolution in case of a ‘no’. The Government of Canada feels it is at the end of the road when it comes to decentralizing powers to Québec. This is certainly not the case in the UK where there is lots of room to push devolution further.

The Québec case tends to suggest that there might be some sort of window for the politics of independence. After the 1995 referendum, many people felt that there would soon be another referendum on Québec independence, but Quebeckers never showed any appetite for it. In that sense, a strong showing of the ‘yes’ side in a losing effort is not a good predictor for anything.

—

This piece originally appeared on the LSE Politics and Policy blog

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of Democratic Audit, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/WFNrNp

—

André Lecours is Associate Professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. His main research interests are Canadian politics, European politics, nationalism (with a focus on Quebec, Scotland, Flanders, Catalonia and the Basque country) and federalism. He is the editor of New Institutionalism. Theory and Analysis published by the University of Toronto Press in 2005, the author of Basque Nationalism and the Spanish State (University of Nevada Press, 2007), and the co-author (with Daniel Béland) of Nationalism and Social Policy. The Politics of Territorial Solidarity (Oxford University Press, 2008).

André Lecours is Associate Professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. His main research interests are Canadian politics, European politics, nationalism (with a focus on Quebec, Scotland, Flanders, Catalonia and the Basque country) and federalism. He is the editor of New Institutionalism. Theory and Analysis published by the University of Toronto Press in 2005, the author of Basque Nationalism and the Spanish State (University of Nevada Press, 2007), and the co-author (with Daniel Béland) of Nationalism and Social Policy. The Politics of Territorial Solidarity (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

What the independence referendums in Québec tell us about Scotland https://t.co/p8xiSt6leG

What do Quebec’s independence referendum’s teach us about the Scotland? https://t.co/e3PvoSlaAt

#CompGov RT @democraticaudit: What do Quebec’s independence referendum’s teach us about the Scotland? https://t.co/paL1F6olxp

What the independence referendums in Québec suggest about Scotland https://t.co/Tna4tFOKYq

Long way ahead! RT @democraticaudit: What the independence referendums in Québec suggest about Scotland https://t.co/3Gri7rgojZ

Lessons from Québec for #indyref: https://t.co/zF7EEjc3Vo A more positive & visible Yes campaign is no guarantee of momentum or success.

What the independence referendums in Québec suggest about Scotland https://t.co/AvoRYfSxCY