Strong sub-national parties do not automatically drive apart voter preferences at simultaneous multi-level elections

Do electoral preferences in democracies differ when voters cast their ballots at general and regional electoral arenas on the same day, and if so, why? Valenyna Romanava argues that this isn’t necessarily the case, with evidence from Belgium, France, Ukraine and Sweden showing that there is no single iron-clad rule in this regard.

The leading theoretical framework for studying multi-level elections – the second-order election theory – assumes that regional electoral contests are second-order elections, i.e. they suffer from lower turnout, electoral losses of parties in office, and electoral gains of opposition, small, and new parties. In theory, the second-order election effects of regional elections should be absent when general and regional elections are held on the same day. Is it the case in practice?

Scholars find that the second-order election effects of regional elections decrease in regions with strong decision-making power and distinct territorial identities when they are politicised by regional parties, and simultaneous voting tends to be more congruent than non-simultaneous voting.

This study seeks to check whether:

- regional elections held on the same day as general elections have second-order election effects;

- regional elections, which are held simultaneously with general elections, have fewer second-order election effects in regions with strong regional autonomy;

- in regions where regional parties win seats in regional legislatures or assemblies/councils there are fewer second-order election effects at simultaneous multi-level elections.

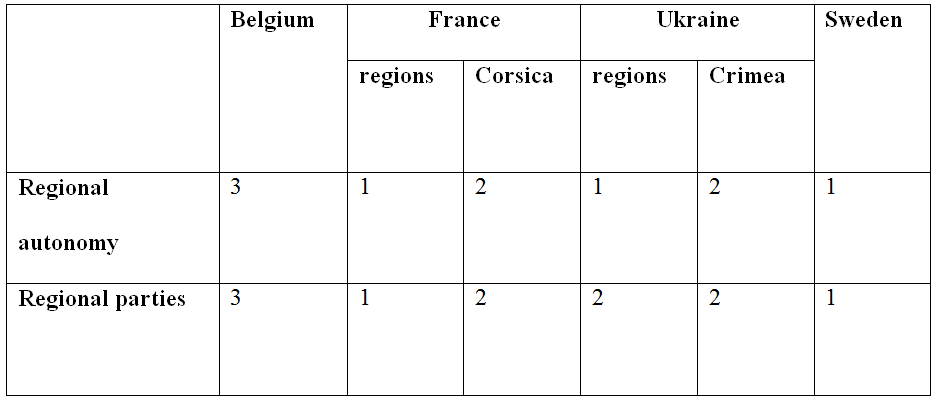

In order to answer these questions, I investigate the cases of simultaneous multi-level elections with the highest possible variation of regional autonomy and regional parties. Strong regional autonomy is found in federations (score: 3); medium regional autonomy – in those regions of unitary states that have more institutional competencies than other regions in the same states (score: 2); weak regional autonomy – in regions of unitary states with no special institutional arrangements (score: 1). Those regions where only regional parties win seats in regional offices score 3.

Those regions where statewide and regional parties pass the electoral threshold at regional elections score 2. Those regions where regional parties do not gain seats in regional legislatures or assemblies/councils score 1. I select cases where simultaneous multi-level elections follow the same electoral rules and are held in democracies. Thus, I investigate simultaneous multi-level elections in Belgium (1995 and 1999), France (1986), Sweden (2002, 2006, 2010), and Ukraine (2006) (see Table 1 please).

Table 1: Simultaneous multi-elections in Belgium, France, Sweden and Ukraine

Rows represent the two explanatory variables, according to the framework of Jeffery and Hough (2009). Columns represent cases. The Table is compiled by the author.

My investigation shows that in the cases of regional elections, which are held on the same day as general elections, there are second-order election effects only in two cases:

a) in regions where regional autonomy is weak and no regional parties win regional elections.

Three subsequent multi-level elections in Sweden prove that there are some dynamics across multi-level arenas even when regional autonomy is the same and there are no regional parties in regional assemblies. In 2002 the party in office performed slightly worse at regional elections (with the exception of Stockholm and Skane), while the opposition gained more votes (in all Swedish regions). At the 2006 regional elections there were nine regions where the party in office performed slightly better. The opposition performed slightly worse at regional elections in all counties except Stockholm. In 2010, the new party in office – the Moderate Party – lost votes at regional electoral contests, while the new opposition – the Social Democrats – attracted more support at regional elections in most regions.

b) in regions where (i) regional autonomy is very strong and (ii) only regional parties gain seats in regional offices.

In 1995 and 1999 multi-level voting in Flanders and Wallonia (Belgium) demonstrated the stability of parties’ vote shares across multi-level arenas. In 1995 the average difference was tiny (1%). In 1999 it increased in Wallonia: the party in office (PS) attracted 3.38% more at regional elections, while the opposition (PRL-FDF) lost votes (2.33%).

Regional elections, when held on the same day as general elections, have fewer second-order election effects in regions with strong regional autonomy only in cases where regional autonomy is relatively strong and statewide and regional parties win regional elections.

In France the opposition (RPR-UDF) lost the most (19.18%) at regional elections in Corsica, which has its regional parliament and its regional executive. Surprisingly, the electoral performance of the party in office at Corsican regional elections did not change much (it was about 1% different). In Ukraine, regional elections in the only autonomous republic, which elects its regional parliament and appoints its regional government – Crimea – did not show many second-order election effects either. Even though the opposition formed a bloc with a regional party at regional elections in Crimea, it lost 25.46% of its parliamentary vote.

Moreover, the second-order election effects of regional elections can drop, when regional autonomy is not very strong in absolute terms, but is strengthened by minor institutional arrangements (such as in two cities with a special status in Ukraine: Kyiv and Sevastopil).

In Kyiv, a regional bloc gained the highest vote share at regional elections in Ukraine (the Chernovetskyi Bloc, 12.93%). The Bloc’s manifesto prioritised regional interests and largely ignored the electoral competition of statewide parties. Regional parties and special institutional status seem to reduce the second-order election effects in Kyiv and Sevastopil. Interestingly, strengthened regional autonomy does not automatically affect second-order election effects at simultaneous multi-level elections. Instead, regional elections in such constituencies represent classic second-order electoral contests.

In Sweden, at the 2010 regional elections the biggest losses of the party in office were found in the County of Kalmar (5.70%). The party in power lost the most in the County of Skane (4.80%). In the County of West Gotaland the party in power lost 4%. In regions where regional parties win seats in regional legislatures or assemblies/councils, there are only partial second-order election effects at simultaneous multi-level elections.

In France, the 1986 regional elections in Corsica demonstrated few second-order election effects. Corsican regional parties won 7.06%. The opposition (RPR-UDF) lost 19.18%. The second biggest loss of the opposition (11.87%) was found in Pays-de-La-Loire, where regional parties stood for regional elections, but did not pass the electoral threshold. In Ukraine (2006), regional parties and blocs won seats at regional elections in eight instances. These eight included two cities with a special status and Crimea and five cases were regions (oblasts) with no special institutional arrangements: Volyn, Dnipropetrovsk, Zakarpattya, Ivano-Frankivsk and Lviv oblasts.

Thus, regional parties do not automatically drive simultaneous multi-level elections apart. Instead, this is the case only when strong regional parties operate in regions with medium regional autonomy or special institutional arrangements.

Thus, electoral preferences in democracies can differ when voters cast their ballots at general and regional electoral arenas on the same day. However, regional elections in strong regional autonomies where regional parties win seats in legislatures or assemblies do not automatically produce electoral maps, which are distinct from the electoral maps generated at simultaneous general elections in the same regions. When the same parties contest multi-level elections, the electoral outcomes are largely the same even in a highly regionalised federation. This is not the case only

- in regions that have special institutional arrangements (which can be relatively modest from a world-wide perspective)

- when statewide and regional parties win seats in regional assemblies.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1tVJajw

—

Dr Valentyna Romanova is a Senior Expert at the Institute for Strategic Studies ‘New Ukraine’. This study is based on Romanova’s peer-reviewed research article at Politics. Her contact details are: Valentyna Romanova, Institute for Strategic Studies ‘New Ukraine’, office 89, 5/24 Irynynska Street, Kyiv, Ukraine, 01001; e-mail: vromanova@ukr.net.

Dr Valentyna Romanova is a Senior Expert at the Institute for Strategic Studies ‘New Ukraine’. This study is based on Romanova’s peer-reviewed research article at Politics. Her contact details are: Valentyna Romanova, Institute for Strategic Studies ‘New Ukraine’, office 89, 5/24 Irynynska Street, Kyiv, Ukraine, 01001; e-mail: vromanova@ukr.net.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Strong sub-national parties do not automatically drive apart voter preferences at simultaneous multi-level elections https://t.co/WpAII9SgH9

Strong sub-national parties do not automatically drive apart electoral preferences at simultaneous multi-level e… https://t.co/bjAjD7Vv0a

Strong sub-national parties don’t automatically drive apart electoral preferences at multi-level elections https://t.co/Mb3UfeTGVP

Strong sub-national parties do not automatically drive apart electoral preferences at simultaneous… https://t.co/tdBDxkRNax