Inside immigration detention centres: Uncoupling detention from a criminal justice imagination

Mary Bosworth‘s research investigates immigration detentions centres in the UK. She argues that the potentially open-ended nature of detention has a profound effect on staff and detainees, making it difficult for the former to plan a regime while, for the latter, creating an environment of uncertainty. The current system is not inevitable, and so, she argues, we need to spend more time thinking about why we detain foreigners and treat them in the way we do.

As the British government holds its first public inquiry into the conditions and nature of immigration detention, it is a good time to take stock of this form of custody. These institutions are volatile and contested sites. They are also places about which we know very little. What is their goal? How are they justified? Who is detained and why? What is detention like?

Although the British government has had the power to incarcerate foreign nationals since the passage of the Aliens Act in 1905, they used this power sparingly until the 1990s other than in times of war. For many years, asylum seekers, foreign ex-offenders, and those without immigration status were kept in prison, or for very short periods of time in holding rooms at ports and airports. In 1970 the British government opened the first purpose built institution to hold people for immigration matters, the Harmondsworth Immigration Detention Unit, on the site of today’s high-security facility, IRC Colnbrook. From that point first slowly and then, under the premiership of Tony Blair, more rapidly, they began to establish the national system we have today. All centres are run, under contract and on behalf of the Home Office, by one of a series of private companies or by HM Prison Service.

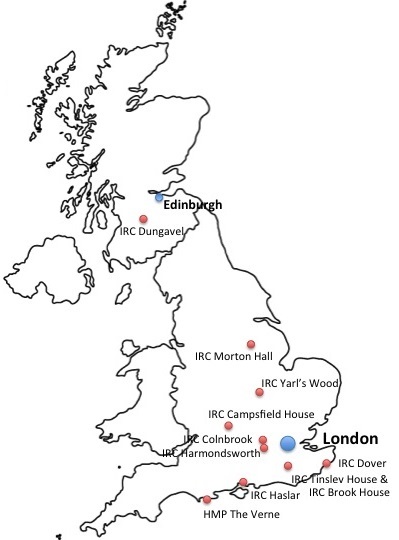

In comparison to other forms of custody as well as to the estimates of the sum of undocumented migrants in the community, the numbers held under Immigration Act powers are low; 3,000 women and men on any given day are confined in 10 immigration removal centres (IRCs) scattered throughout the country. This figure starts to swell if we include the 1,000 or so who remain in prison post-sentence (or who are sent there from IRCs), held under immigration act powers, and the small number of families in the ‘pre-departure accommodation’ at Cedars. Another hundred or so sit in short term holding facilities at ports and airports within the UK and across the channel in Calais and Dunkirk. Still more are held in police cells, hospitals and Home Office reporting centres.

Detainees are drawn from across the globe yet tend to congregate from former British colonies. Women make up around 10 per cent of the total population, and are concentrated in one establishment, Yarl’s Wood, although small numbers are also held in Colnbrook and Dungavel. They are also detained as parts of family groups in Tinsley House and Cedars.

Over the course of a year, the sum of detainees rises ten-fold, signalling the importance of time in understanding immigration detention. For most, confinement is relatively brief. Yet, despite the appellation of such places as removal centres, not everyone in them is sent away. Around 40 per cent of detainees are released back into the UK community. The rest are returned to the country of their birth or to a ‘safe’ third country, where they were first documented as an asylum seeker. For a small handful of people, detention lasts a long time. Despite various attempts to speed up the immigration process, all centres house some people for over six months at a time, since, unlike the rest of Europe, the UK has refused to institute a statutory time limit to detention.

The potentially open-ended nature of detention has a profound effect on staff and detainees, making it difficult for the former to plan a regime while, for the latter, creating an environment of uncertainty. There is no clear justification for this open-ended policy and it has few supporters. In my own research I found nobody, from within the custodial sector, detainee populations or Home Office who thought it was a good idea. ‘They just need to change the law to get rid of indefinite detention’, one member of the senior management team in Yarl’s Wood said bluntly. ‘We don’t hold any prisoners like that. It doesn’t make sense.’

Some find the uncertainty of detention harder to bear than others. IRCs are full of vulnerable people. Specific groups like the young, the mentally ill, torture survivors, asylum seekers, pregnant women, are often singled out. But the truth is that research finds that the longer anyone is detained the harder they find it to cope. Indeed, in my research with Blerina Kellezi, ex-prisoners, who are often a group with few supporters, struggled to understand what was happening to them and how to manage with detention more than others. Such people, who had completed a prison sentence, were particularly quick to criticize detention custody officers, the lack of meaningful work and education offerings in detention and, above all, their uncertainty over its duration.

Some find the uncertainty of detention harder to bear than others. IRCs are full of vulnerable people. Specific groups like the young, the mentally ill, torture survivors, asylum seekers, pregnant women, are often singled out. But the truth is that research finds that the longer anyone is detained the harder they find it to cope. Indeed, in my research with Blerina Kellezi, ex-prisoners, who are often a group with few supporters, struggled to understand what was happening to them and how to manage with detention more than others. Such people, who had completed a prison sentence, were particularly quick to criticize detention custody officers, the lack of meaningful work and education offerings in detention and, above all, their uncertainty over its duration.

Despite the best efforts of those working in detention, detainees across the board—whether former prisoners or visa over-stayers—articulate a number of common concerns. Reflecting the enduring nature of Empire, as well as their period of residence in the UK, most of those confined speak some English. However, few are fully literate. Many have great difficulty reading the Home Office documentation relating to their immigration case or the signs around the removal centres advertising courses or events. They may also find it hard to communicate with custody officers and one another. Many are confused about why they are detained and nobody knows how long they will be there. They find it difficult, despite the availability of mobile phones, to maintain contact with their families and, even though centres arrange family-day visits to assist with contact with children, few take this option.

Detainees are often unable to obtain a trustworthy and effective immigration solicitor. Fewer and fewer of them are entitled to legal aid. Many are frustrated by the limited amount of paid work and education in detention, particularly if they have served a prison sentence during which they have taken advantage of a wide range of courses and programmes. Healthcare remains, across the board, a source of great anxiety.

Such complaints are likely to be disheartening for centre managers and staff, as well as for those working in immigration, some of whom are actively striving to improve conditions behind bars. The findings do not make for optimistic reading for detainees, their families, or their supporters. For all concerned, these problems are also likely to be familiar. The question remains, then, why are these failings so entrenched and why do they have such little impact on the legitimacy of the practice of immigration detention?

It seems plausible that there may be limitations inherent in the contracts—although, since these are protected, private documents, it is not possible to be sure about their content. Likewise, it is clear that most people in detention do not wish to be deported, so they are hardly likely to be satisfied with their treatment. Instead, they are anxious, depressed, and often angry.

Yet, there is also a more substantive point to be made about the utilitarian justification of detention as no more than a means to the end of enforcing deportation. Unlike prisons, with which they are often compared, detention centres have no historically grounded (albeit contested) set of rationales. Despite some populist aspirations to the contrary, and notwithstanding their effect, IRCs are not officially designed to punish or deter. They also cannot rehabilitate, since citizenship cannot be earned or acquired within them. At most, then they simply incapacitate; holding people until the real activity (deportation or removal) occurs. Yet, given that nearly half of those detained each year are returned to the community even this justification is easily set aside.

According to one senior Home Office employee, IRCs ‘are not meant to be destinations.’ They are, in this view, merely a regrettable precursor to deportation or removal. Just as legal scholars argued in the 1970s that approaching punishment in a purely utilitarian fashion was unjust, so too it seems clear that considering detention in this way is a large part of the problem. It also conveniently overlooks the manner in which over a relatively short period, immigration detention has become a fixed part of British migration control. What we need instead is greater attention on detention centres and a tougher examination of those they house in their own terms. To do so effectively, we must uncouple detention from a criminal justice imagination and generate new ideas and language to understand them.

In so doing, we may need to leave behind the traditional vocabulary that centres on legitimacy in our analysis of state power. On what basis might we find a shared perspective and beliefs? In a global world, and in institutions situated at the limits of the nation state, how useful is this term anyway? Instead, we should concentrate on why we detain foreigners and treat them in the way we do. In terms of the IRCs, such questions become quite simple. What is detention like? What is it for? What is its effect?

Why do foreigners, particularly in a postcolonial, multicultural country like the UK, generate such a response? What is it about those without citizenship that enables us (morally and ethically) to perceive them differently from ourselves? What are the costs to us, to those who work with them and to detainees of this estrangement? Given the enormous financial and personal burdens, what might it take to think and act otherwise? Although detainees may not, by law, have the right to remain, they do have the right to call on us as fellow human beings. In their current form, detention centres make it hard to recognise that right and, as those giving evidence to the current parliament inquiry suggests, this situation needs to change.

—

This post originally appeared on the LSE Politics and Policy blog and is reposted with permission

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is:

—

Mary Bosworth is Professor in Criminology at the University of Oxford and, concurrently, Professor of Criminology at Monash University Australia. At Oxford she is Director of Border Criminologies (@bordercrim), an interdisciplinary research group on the intersections of criminal justice and border control based at the Centre for Criminology. She has been conducting research inside Britain’s immigration removal centres since 2009, and has a book, Inside Immigration Detention (OUP, 2014) out in September.

Mary Bosworth is Professor in Criminology at the University of Oxford and, concurrently, Professor of Criminology at Monash University Australia. At Oxford she is Director of Border Criminologies (@bordercrim), an interdisciplinary research group on the intersections of criminal justice and border control based at the Centre for Criminology. She has been conducting research inside Britain’s immigration removal centres since 2009, and has a book, Inside Immigration Detention (OUP, 2014) out in September.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

New on DA today: Mary Bosworth on Home Office immigration centres https://t.co/QIXyeTPmIO

Inside immigration detention centres: Uncoupling detention from a criminal justice imagination https://t.co/0OBc8feSiN from @bordercrim

Inside immigration detention centres: Uncoupling detention from a criminal justice imagination https://t.co/ZDpVRlxmbd

Interesting piece by Mary Bosworth, @Bordercrim director on immigration detention centres. @democraticaudit https://t.co/yn1zVDebNg

Inside immigration detention centres: Uncoupling detention from a criminal justice imagination https://t.co/3y8gOlsHMa