Even decentralised parties aren’t immune from the instinct to centralise

Green Parties are often decentralised and highly internally democratic. But how do decentralised party arrangements respond to power, or proximity to power? Looking at the case of the Australian Greens, Narelle Miragliotta and Stewart Jackson find that there has been gradual growth of the party’s national level, even in spite of formal provisions which guarantee the autonomy of the state organisations.

The Australian Greens campaign: Credit: Stephen Hass, CC BY 2.0

One of the distinguishing characteristics of green parties is their preference for models of party organisation that are rooted in the principles of inclusivity and decentralisation. While these values assume a slightly different manifestation in different national systems, what is generally true is that green parties stress decision-making structures that privilege the membership and which value local autonomy.

Both research and experience tell us that electoral success generates strong pressures for green parties to centralise decision-making and to embrace more professionalised party structures. But what is less clear is whether green parties operating in devolved settings are better equipped to manage these tensions and to resist such pressures because of the values that underpin multi-level states. Devolved settings are naturally sympathetic to those same principles of decentralisation and local autonomy that green parties tend to venerate.

However, the case of the Australian Greens reveals that even a federal setting provides only minimal defense against those centralising imperatives that electoral success necessarily invites. This occurs because as the federal parliamentary fraction expands in size it acquires resources and visibility that can serve to bolster the influence and authority of the national organisation, typically at the expense of lower decision-making units of the party.

The Australian Greens: From state parties to a national structure

The Australian Greens was established in 1992, although the party can trace its origins back to the early 1970s. Over the years the Australian Greens have achieved significant representational successes to now claim the mantle as the ‘third force’ electorally, in Australia. While many of these successes were initially made at the state and local level, increasingly electoral gains have occurred at the national level.

A key factor working in favour of the success of the Australian Greens has been the electoral possibilities contained within the Australian political setting. The multiple electoral contexts provide a small party with an opportunity to gain electoral and political exposure while refining campaign skills. This has been seen within other polities, and in the case of green parties is perhaps best exemplified by Die Grunen in Germany, although other green parties such as in Belgium and Switzerland exhibit both strong regional associations and organisational heterogeneity within their respective confederal structures. In Australia, the Greens have made extensive use of campaigning opportunities at all government levels, and built extensive supporter networks to support campaigning and elevate their profile within the electorate, as well as to consolidate their organisational structures and processes.

The legacy of the Australian Green’s formative evolution is that the party’s organisational format is dominated by the state branches. The party’s National Council is controlled by state organisations with more or less equal representation. While there is some ‘national’ representation in the form of non-voting office holders and federal parliamentary representation, this is outweighed by, at times, parochial state self-interest. Nonetheless, there have been more subtle shifts within the party’s decision-making processes, moving power away from state organisations to the national strata.

This can particularly be seen in the development of two key core committees of the party, the Australian Greens Coordinating group (AGCG) and the National Election Campaign Committee (NECC).

The AGCG was not intended to serve as an executive body but to assist the work of the (voluntary) national office holders. The gradually increasing demands upon these roles required additional administrative support, but also an expanded pool of decision makers. As the body now tasked with the direction of the day-to-day operation of the party, the AGCG has also to deal with the increased party financial responsibilities, as well as the legislative-technical matters related to the party registration process. This has required members of the committee to assume an explicitly national focus, away from any state affiliations.

The NECC has existed from the earliest days of the national party, but has slowly expanded its remit from simply coordinating state based campaigns to now directing national advertising campaigns (including expenditure) and national preference negotiations (these negotiations become critical in Australia’s compulsory preferential voting system, where direction from the party is seen as key to influencing supporter allocation of voting preferences).

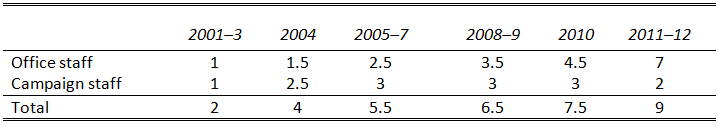

The overall effect of these nationalising campaign objectives has been to standardise and centralise decisions around campaign themes, logo’s and party websites. Local campaign organisations now tend to be reactive to national priorities and campaign methods, even though state bodies still retain formal autonomy in the running of their campaigns. Administrative and campaign imperatives have also led to an increase in national party staffing, in positions such as a National Manager, National Campaign Coordinator, National Fundraiser and National Communication Manager (see Table 1). The national office now surpasses any of the individual state offices in staffing levels.

Table 1: National Staffing Levels of the Australian Greens, 2001–12

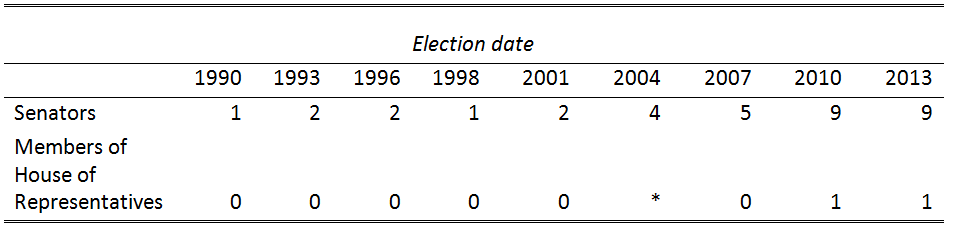

Alongside the growth of the party’s national office has been the expansion of the party’s federal Parliamentary Party (see Table 2). When the Australian Greens had less than five federal MPs, the staff were concentrated within MP’s electorate offices and physically removed from the states and electorates from which the MPs were elected from. However, with the eventual attainment of five (and now 11) federal MPs, and the according of formal Parliamentary Party status, the Office of the Parliamentary Leader has grown, firstly under Senator Bob Brown (now retired) and more recently under Senator Christine Milne, in both size and in access to resources.

With the growth of the parliamentary party has emerged the expectation that the national parliamentary group will undertake tasks that the state branches were previously obliged to perform. This has led to an increasing reliance on the parliamentary party to carry out policy and public communication roles, even though these roles might be expected to be vested in the party organisation. In acquiring these additional responsibilities, it has enabled the parliamentary party to exert influence at all levels of the party, a situation which has been reinforced by the minimal constraints placed on them by the party’s formal rules.

Table 2: Federally Elected MPs of the Australian Greens, 1990-2013

Is centralisation inevitable?

The consolidation of the Australian Greens at a national level does not mean that the party must inexorably centralise. The geospatial isolation and separation between the state organisations, coupled with the party’s own history and decentralising inclination have thus far restrained rampant centralisation of decision-making power within the national strata. While there has been a more subtle erosion of the confederal basis of the Australian Greens, this has not tended to be reflected in the formal rules governing the party.

However, what is generally true is that the expansion in the federal parliamentary group has strengthened the national tier of the party and in the process weakened the confederal basis of the party organisation. It seems that not even a federal setting is a sufficient condition to prevent organisational centralisation and professionalisation once a green party attains a certain measure of electoral success.

—

Note: this post is based on an article in the Government and Opposition Journal. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Narelle Miragliotta is a lecturer in Australian politics. Narelle Miragliotta obtained her PhD (politics) from the University of Western Australia. Dr Miragliotta has broad teaching and research interests in many different aspects of Australian politics, including the politics of the Australian media; green political parties; and Australian elections and electoral systems.

Stewart Jackson is a Lecturer at the University of Sydney

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Tbh, this seems a fuss about nothing. What is the actual story here? ‘Shock: in response to national success, Green Party has more national staffers’.

Even decentralised parties like the Greens aren’t immune from the instinct to centralise https://t.co/oJcaUSDOcB

Even decentralised parties aren’t immune from the instinct to centralise https://t.co/3gIrZ8DRSK https://t.co/H3O0EosMvw

Even decentralised parties aren’t immune from the instinct to centralise https://t.co/zTSMzq44DH via @democraticaudit

Even decentralised parties aren’t immune from the instinct to centralise https://t.co/AIiVjGlc89