The skills needed to be re-elected are different to those needed to be an effective legislator

Osnat Akirav summarises a journal article which examines the ability of legislators to get re-elected by their fulfilling their three roles: legislation, oversight and representation. She also re-examines the claim that most legislators are motivated by a desire to be re-elected, and that this desire determines the utility of their legislative activity toward this end by advertising, credit claiming and position taking. She further argues that different skills are required to be selected as a party’s choice and be re-elected, and to enact legislation. Thus, she distinguishes between two types of legislators—those who are electable and those who are successful in the legislature.

The Israeli Knesset (Credit: Photo Gallery Israeli Ministry of Tourism, CC BY SA 2.0)

Re-election rates have important consequences for the quality of a democracy. Studies found that different candidate selection methods create different behaviours among legislators. Legislators have to raise their own money to lobby for selection by their parties, they try to attract the media through populist issues, they connect with their constituents more intensely, and they become more independent and more oriented toward individual concerns.

Having overcome the first hurdle of being selected by one’s party, there are several factors determine whether a legislator seeking re-election will win; incumbency – political incumbents across systems enjoy a privileged position within their own districts in terms of their visibility, name recognition, and their ability to garner votes by providing services to constituents.

A second factor offered in the literature focuses on the electoral system. Studies show how different electoral systems provide different incentives to politicians, thereby creating different kinds of connections between voters and legislators.The dominant normative claim is that electoral competition is good for democracy because it promotes representation and responsiveness.

The two-stage election process requires legislators to focus on two separate constituencies: the primary constituency and the general election constituency. The primary constituency is the party base, a small subset of voters that are generally more ideological than the more moderate general election constituency. Thus, balancing these interests might prove difficult for legislators. Some electoral systems strengthen the power of the individual, some the power of the parties and some try to balance the power of the individual and the power of the party.

The third explanation is about effectiveness. The basic assumption behind this factor is that active legislators who are considered to be effective in their roles will gain the voters’ support.

The fourth explanation involves charismatic communication skills, which defined as the actor’s demonstrated skills, performance and talent that are pertinent to the main arena in which she/he operates. In an era of mass communication that demands attention both from the voters and from legislators, having communications skills is an essential factor for legislators’ success and their ability to be re-elected.

While communication skills are important, the increasing use of new communication technologies is a prerequisite for directly targeting voters. Such technologies bypass the mass media as well as the party organizations. Hence, the fifth and last explanation revolves around the information revolution, which has accelerated since the invention of the Internet and has an enormous effect on public life. Through the Internet, legislators and parties became transparent and accessible to the public. Information about the legislators’ performance is available on the websites of the parliament and the personal websites of the legislators, and on their Facebook pages. In addition, the new technology makes direct contact between legislators and their constituents simple. Furthermore, parties use their websites during the election period to address the public directly.

Thus, the explanations about the factors affecting the probability of re-election have changed over the time because of changes in candidate selection methods, in the electoral systems, in mass communications and in the technology. Each factor, separately and together, has changed the rules of the political game. Therefore, it is important to examine traditional claims in this area with fresh new data about their existence or relevancy.

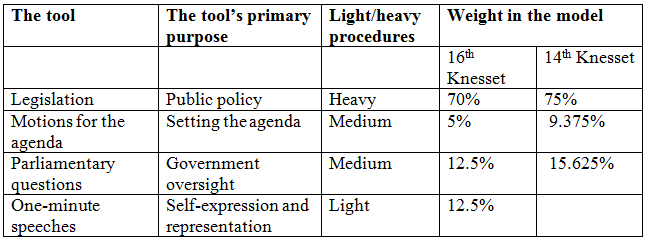

The study suggests a model for examining legislators’ performance by expanding the definition of legislators’ productivity to include the use of the formal tools available to legislators in a specific parliament. Activities defined as formal if they are based on the procedures of the legislatures. Hence, the model includes the use of four tools—legislation, motions for the agenda, parliamentary questions and one-minute speeches.

Table 1: Productivity Model

Table 1 presents the content of the productivity model. The model combines several tools available to legislators in the Israeli parliament (the Knesset). The table indicates their primary purposes, their degree of significance and the weight they have in the model. The model uses a scale from 0 to 100 to measure legislators’ productivity.

The data gathered is from the 14th Knesset (1996-1999) regarding legislators’ formal activities and their re-election to the 15th Knesset. The same kind of data was gathered for legislators from the 16th Knesset (2003-2006).

In order to examine the research hypothesis; the skills needed to be re-elected are different from the skills needed to fulfil the legislators’ roles, we ran a logistic regression for the 14th Knesset with the dependent variable being re-election and four independent variables: productivity, gender, seniority and membership in the coalition/opposition. There were 68 relevant legislators, of whom 10 were not re-elected and 58 were re-elected. None of the independent variables were found to be significant. Hence, in order to be re-elected a legislator does not need to be productive. Instead, legislators need other skills.

Evidence from previous studies is inconclusive about whether active legislators who are considered to be effective in their roles will gain the voters’ support in their re-election efforts. Some have established such a connection while much of the scholarship about legislative representation in at least the U.S.A. makes exactly the case that other skills, or at least constituent-oriented activity outside the formal sphere, can make an electoral difference and that legislators therefore invest in it.

In their book ‘The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence, Bruce Cain, John Ferejohn, and Morris Fiorina describe the behaviour of representatives in the United States and Great Britain and the response of their constituents as well. They showed how congressmen and members of Parliament earn personalized support and how this attenuates their ties to national leaders and parties. Fiorina found that the incumbency advantage ascended mostly because of the dramatic increased of the “Casework Style” of representation. And few years later he found that everyone started using the Casework Style, hence, a high level of constituency service became the norm and was expected by the voters.

There is substantial variation in what legislators claim credit for and how often they claim credit for expenditures made for their districts. Our findings for the 14th Knesset accord with the latter. Hence, we need to look for other explanations, other skills that help legislators get re-elected. In addition, re-election seems to be unrelated to whether the MK is male or female, a member of the coalition or the opposition, or a senior member or junior member.

For the 16th Knesset, we ran a logistic regression with re-election as the dependent variable and three independent variables: productivity, gender and seniority. In the 16th Knesset, senior legislators were 4.7 times more likely to be re-elected than junior legislators. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that senior incumbents are re-elected time after time. We did not find any significant difference in the productivity of junior MKs and senior MKs. Therefore, in the 16th Knesset, which was less productive than the 14th Knesset, incumbency was more significant than productivity.

The gender variable was almost significant considering the fact that there were 9 women and 61 men. Men were more likely to be re-elected. Several scholars have looked at the role of gender in parliaments. All of them found that female politicians bolster the position of women’s interests and that female politicians invest much more effort than male politicians in order to justify their presence in parliament. Nevertheless, we found no significant difference in the productivity of male and female MKs. Again, the ability to be re-elected seems to have more to do with being a member of the male elite than about being productive.

It seems as if the skills needed to be re-elected are different from the skills needed to fulfill the legislators’ roles of legislation, oversight and representation. In this respect we can identify two types of legislators–the “electable” type and the “legislative activity” type. Legislators seem to have a hard time being both. David Mayhew has claimed that most legislators are motivated by a desire to be re-elected, and that this desire motivates their activity toward this end by advertising, credit claiming and position taking.

However, the reality when Mayhew presented his electoral connection claim is significantly different from the reality of the last two decades. There have been changes in almost the entire traditional political environment including in the candidate selection methods, the electoral systems, mass communications and technology, each of which separately and taken together have changed the rules of the political game. Thus, working in the legislature is just one of the factors but no longer sufficient for being re-elected.

Using fresh data, we examined the traditional claims about the factors that lead to a legislator’s re-election. We found that while some still matter, others are less relevant than they were in the past. We argue that different skills are required for different roles. If a legislator wants to be re-elected, he/she needs to understand that there is one set of skills to use for getting elected such as charismatic communication skills, the awareness and the ability to use new technologies to communicate with the voters, and the investment of time in informal activities. It takes a different set of skills to use to fulfil the role of legislator. Dror, in a 2011 book, counsels leaders to surround themselves with professional staff who will help them fulfil their roles. The same insight may be relevant to legislators. In order to get re-elected, choose a professional staff with skills in this area. After being elected, choose a professional staff that will help you to enact legislate, oversee the government and represent your constituency.

The lack of a relationship between legislative productivity and re-election has major implications for both the political process in democracies and candidates. We must ask ourselves whether the format in which candidates currently campaign for re-election really results in the election of those who are best qualified to do the job of legislators. If we conclude that the skills needed to be re-elected are not congruent with those needed to be a productive legislator, then the answer may be “no.” Furthermore, if there is no association between legislative productivity and re-election, what motivation does a legislator have to fulfil the role for which he or she was elected?

Finally, from a practical point of view, those seeking re-election would do well to avail themselves of a professional staff who can help them develop the skills necessary to achieve this goal. Once in office, these legislators should consider other advisers whose expertise lies in helping the legislator fulfil the role for which he or she was elected.

—

Note: for full academic references and data analysis, see the full article in the Government and Opposition journal. This piece represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Osnat Akirav is a senior lecturer in Political Science at the Western Galilee College, Israel and the head of the department of political science at the Western Galilee College. She holds a PhD from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Her specialization is in legislative studies, setting the agenda, candidate selection methods, local government, gender and politics, minorities and politics, research methods and Israeli political system. She has numerous publications on the representative behavior in local government and in parliaments. She served 10 years as local council representative.

Osnat Akirav is a senior lecturer in Political Science at the Western Galilee College, Israel and the head of the department of political science at the Western Galilee College. She holds a PhD from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Her specialization is in legislative studies, setting the agenda, candidate selection methods, local government, gender and politics, minorities and politics, research methods and Israeli political system. She has numerous publications on the representative behavior in local government and in parliaments. She served 10 years as local council representative.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Why, unfortunately, Andrew Adonis will have an uphill battle to be Mayor of London, despite being best man for it… https://t.co/d2j2gUHkpf

The skills needed to be re-elected are different than the skills needed to legislate https://t.co/kVxuZ3mUkD

The skills needed to be re-elected are different to those needed to be an effective legislator says Osnat Akirav https://t.co/D1N6OBafra

Chcesz rządzić 2 kadencje czy tworzyć dobre prawo? https://t.co/FafMntuaX9 https://t.co/TRBkJppvAn via @LSEPubAffairs

The skills needed to be re-elected are different to those needed to be an effective legislator https://t.co/qYBJShGlFz https://t.co/7kZtDi14ss

The skills needed to be re-elected are different to those needed to be an effective legislator https://t.co/VdTG1bs8FT