Crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy, and can force us to think in new ways about solving entrenched problems

Mark Chou from the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne reflects on a recent book by David Ruciman which explains the nature of crisis in democracies, and the various ways it is overcome. He argues that crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy, but can force us to think in new and innovative ways about how we organise our democratic societies.

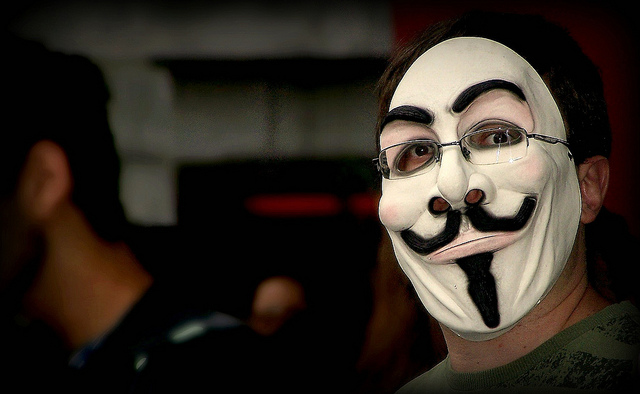

Credit: Daniel Zanini H., CC BY 2.0

In The Confidence Trap, probably one of the most talked about books on democracy written in recent years, David Runciman tackles what he calls the history of democracy in crisis.

Like the GFC which consumed global financial markets, democracy too has been embroiled its own ‘crisis talk’ in recent years. From Britain, Australia and the United States to Egypt, Thailand and Russia, we’ve seen firsthand how vulnerable democracies – both new and established – can be. But unique as these democratic crises may feel, Runciman reminds us that they are in fact just the latest in a long line of democracies in crisis. Which should tell us something.

“Things look bad,” an undeniable fact which Runciman documents in The Confidence Trap, “but the historical record of democracy suggests that nothing is as bad as it seems.” In other words, whatever its ailments that democracy remains “the only game in town” should be telling.

Sure democracies will find themselves in a state of crisis from time to time; in this way they’re no different to any other form of government. Yet a closer look at the longer history of democracy will suggest that, despite or even because of the crises it generates, democracy is an unusually resilient beast. This is Runciman’s point. Democracies may have a knack for getting themselves into crises but they also have the capacity to stumble their way through them relatively unscathed.

As a book, The Confidence Trap does a fairly good job of examining how select democracies (primarily the United States as John Keane recently pointed out) have survived crises of the past 100 years. It also offers a clear explanation of why democracies so frequently implicate themselves in crises – a lot, in Runciman’s estimation, has to do with the fact that democratic politics remains “as childish and petulant as it has ever been: we squabble, we moan, we despair.” This condemnation of democracy is, in some respects, as old as democracy itself.

However what Runciman’s account of democracy in crisis does not do, or do enough of, is unpack the concept of crisis itself, particularly the democratic variant. The assumption is simply that crisis is a deleterious thing, something which democracies should avoid if at all possible. In fact, for a book about the crisis of democracy the most he says on the matter is this: “Crises are often perceived as moments of truth, when we discover what’s really important. But democratic crises are not like that. They are moments of deep confusion and uncertainty. Nothing is revealed. The advantages of democracy do no suddenly become clear; they remain jumbled together with the disadvantages.”

Is this really the case? Is that all there is to say about crisis? The simple and short answer is no. Crisis is not intrinsically problematic. Nor is it necessarily a bad thing.

The meaning of crisis

It’s certainly true that, conventionally understood, “‘crisis of democracy’ is a phrase used to describe pessimistic fears of destruction or internal disarray”, as Joris Gijsenbergh, Saskia Hollander, Tim Houwen, and Wim De Jong write in their volumeCreative Crises of Democracy

In everyday language, crisis has become synonymous with catastrophe, disorder and disease. Rightly or wrong, it now invokes a sense that something is urgently, even fundamentally, wrong. It’s understandable then that when it comes to something like a crisis of democracy we tend naturally to assume the worst, fearing for the health and vitality of democracy. But it doesn’t need to be that way at all.

By examining the concept’s etymological root, as Gijsenbergh et al. ask that we do, we can see crisis merely as “a critical, decisive moment with an unknown outcome.” Here, the part to concentrate on is not the “outcome”, because that is yet to be determined. Instead, it is the “critical, decisive moment” (i.e. the crisis itself) that most deserves our attention.

Such an interpretation echoes the early work of the German historian Reinhart Koselleck, whose detailed genealogy of the concept tells us that in its earliest ‘Greek’ iteration crisis “imposed choices between stark alternatives – right or wrong, salvation or damnation, life or death. ”Later, as the concept spread to other domains of life, it became considered as a metaphor for “a state of greater or lesser permanence, as in a longer or shorter transition towards something better or worse or towards something altogether different.”

Seeing crisis this way does a number of things. First it helps rescue the concept of crisis from the populist discourse of doom and gloom. A crisis can lead to disaster, but it doesn’t have to. It can just as easily create a rupture that opens space for new actors and practices. More importantly for democrats, a nuanced understanding of crisis will see us embrace political crossroads, upheavals and turning points with a modicum of optimism.

Of course, it’s worth pointing out that democracy can move beyond itself or take on new forms in the aftermath of a crisis. At times, this will be a regrettable thing. Past crises we’ve witnessed have certainly led to the retrenchment or erosion of certain democratic rights and freedoms. Think the United States, and most Western democracies for that matter, in the wake of 9/11.

However this won’t always be the case.

Instances such as Occupy demonstrate how post-crisis democratic configurations and movements can exhibit democratic practices in new and unexpected ways. They may appear strange, even un-democratic, when compared to democracy as it has been conventionally understood – through voting patterns, party politics and institutional responsiveness. In this way, our fear of crisis may just be masking a deeper sense of democratic nostalgia.

But that is part of what makes crises challenging: they force democrats to revise what they think democracy is and how it can subsequently be practiced.

For Gijsenbergh et al., this is why crises are essentially creative moments. Far from just “referring to the demise of democracy,” crises force democrats to push against and beyond staid democratic conventions. They can inspire and provoke, leading with a bit of luck to an “escalation and intensification of the competition to define the substance, forms, and limits of democracy.”

Even when the results are destabilising and counter-productive, a crisis will arguably have done democracy more good than harm.

—

Note: This post originally appeared on the Crick Institute blog. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Mark Chou is lecturer in politics at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Australia. His latest book, Democracy Against Itself: Sustaining an Unsustainable Idea, explores how different democracies have failed and the lessons we can take away from these troubled democracies. He is also co-editor of Democratic Theory: An Interdisciplinary Journal, which will feature a special issue on the crisis of democracy in 2014.

Mark Chou is lecturer in politics at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Australia. His latest book, Democracy Against Itself: Sustaining an Unsustainable Idea, explores how different democracies have failed and the lessons we can take away from these troubled democracies. He is also co-editor of Democratic Theory: An Interdisciplinary Journal, which will feature a special issue on the crisis of democracy in 2014.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy https://t.co/flzMRwnvoX says Mark Chou

RT @PJDunleavy: Crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy, and can force us to think in new ways about solving entrenched problems http:/…

Crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy, and can force us to think in new ways about solving entrenched problems https://t.co/ccw8jj8jrj

Crises aren’t necessarily bad for democracy, and can force us to think in new ways about solving entrenched problems https://t.co/kbIJewidIp