Parish councils can empower local communities, but we need more of them in cities

Parish councils, the lowest level of local government in the UK, tend to be synonymous with rural communities. But the government has taken steps to make it easier to create new councils, which have been seized upon by campaigners in a number of urban areas. In this post, Richard Berry discusses the trend and considers the prospects of an increasing number of parish councils transforming UK local government.

Sutton Coldfield in Birmingham, where residents are seeking to create their own parish council. Credit: Graham Taylor, CC BY-SA 2.0

JK Rowling’s first novel for adults, post-Potter, was centred on the business of a fictional parish council, which provided the forum for the class, racial and ideological tensions within a single town to be played out. Despite the spotlight provided by our most successful living novelist, however, most of us are probably unaware of the work of parish councils. There are over 12,000 of them in the UK, mainly in rural areas. In England, about 35% of the population lives in an area served by a parish council.

Parish councils are, in effect, mini-local authorities, elected by the local community. Although they have few formal responsibilities, many are active in running local services and amenities, and all have the power to levy a precept on top of local council tax to fund their work. They are important players in local governance in many areas, therefore, but there is potential for them to make a bigger contribution to UK democracy.

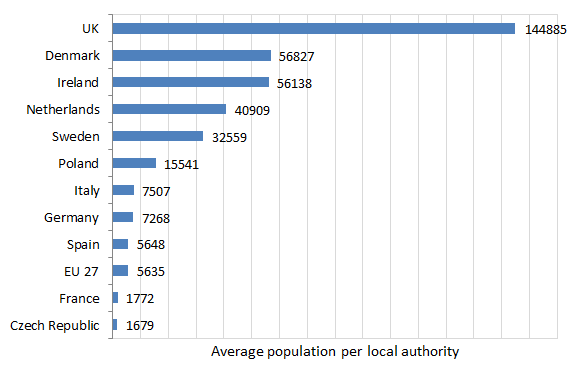

This matters because local authorities in the UK are not very local. They tend to serve much larger populations than their foreign counterparts, with fewer elected representatives per constituent. In some places ‘the council’ can seem like a distant institution, whose boundaries don’t necessarily correspond to the communities people think of as their local area. Figure 1 below compares the average population served by local authorities in the UK and selected EU countries.

Average population served, local authorities in the UK, EU and selected EU countries, 2012

Source: Calculated from Council of European Municipalities and Regions, 2013

Source: Calculated from Council of European Municipalities and Regions, 2013

Support from central and local government

The government has given a clear indication that it would like more parish councils to be established. First of all, it is providing grants of up to £10,000 for local campaigns seeking to set up new councils. It has also proposed changing the law to make it easier and quicker for community groups to establish a parish council (a draft Legislative Reform Order has been published for consultation). The proportion of local voters who need to sign a petition to trigger an application to the local authority would be reduced from 10% to 7.5%, and for some established community groups (those that already have a neighbourhood plan) no petition would be needed.

Local authorities – which make the decision on whether to grant parish council status – would also be required to complete a review of all proposals within 12 months. This latter measure is designed to prevent undue delays from reluctant authorities. The National Association of Local Councils (NALC), which represents parish councils, has called for an independent appeals process for rejected applications, but this is not the government’s plans. Cllr Ken Browse, Chair of the NALC, has said:

Local councils are popular with people and can really make a difference, and for too long communities have battled with burdensome bureaucracy to get them created. The proposals to remove red tape, simplify and streamline the current process are common sense. Of fundamental importance is a strong presumption in favour of creation and avoiding community groups being pitted against their principal council in a David versus Goliath battle.

One local authority has developed innovative proposals to devolve power to parish councils. Buckinghamshire County Council is inviting parish councils in the county to take responsibility for some transport services currently delivered at county level, with funding transferred downwards. Some aspects of the proposals appear prescriptive, for instance the preference for working with clusters of parish councils rather than individual bodies; it is important parish councils are not treated merely as delivery arms of higher authorities. However, this represents an important test of how parish councils can develop.

Parish councils in urban areas

The key test of the model will be whether the number of parish councils increases significantly in the coming years, especially in urban areas. There have been encouraging developments recently. In particular, London now has a single parish council; before a change in the law in 2007, parish councils were not allowed to be established in the capital. The first is the Queens Park Community Council, covering a single ward in the City of Westminster, which grew out of a vibrant community forum following several years of campaigning for parish status.

Queens Park held its first elections simultaneously with the London borough elections in May 2014, electing twelve new councillors in four wards. The outcome was mixed, from a democratic perspective. Two of the wards did not need to hold a vote because only three candidates put themselves forward in each ward, meaning all were automatically elected. In the contested wards, however, turnout was relatively strong at 38%, higher than the 32% who voted in the borough elections across Westminster.

There are a number of other campaigns to establish parish councils in urban areas. London has several others: in Plumstead, Charlton, Barking Reach and London Fields, Hackney. Central Bradford , Fenton in Stoke-on-Trent, Sutton Coldfield in Birmingham and several parts of Peterborough all have ongoing campaigns at different stages. If these and others prove successful, urban local government could look very different ten years from now, and the pressure for genuine devolution of power to communities may prove irresistible.

—

Note: This post represents the views of the author and does not give the position of Democratic Audit or LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding.

—

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly, and runs the Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit and the LSE Public Policy Group. He is a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly, and runs the Health Election Data website. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Parish councils can empower local communities, but we need more of them in cities https://t.co/cov8GiaRj1 says @richard3berry

Parish councils can empower local communities, but we need more of them in cities https://t.co/jNyNVCWZqA

RT @NALC: .@NALC supports calls for more parish councils to address democratic deficit in UK and promote #devolution https://t.co/jsLFjMUU3M…

[…] Parish councils, the lowest level of local government in the UK, tend to be synonymous with rural communities. But the government has taken steps to make it easier to create new councils, which hav… […]

After @GoQueensPark, where next for parish councils in UK cities? https://t.co/g6ohZNNEPO

@centreforlondon: Is UK local government too remote? Via @PJDunleavy https://t.co/IeIQSA1WcV https://t.co/qvISs4CWVl #devolution

RT @centreforlondon: Is UK local government too remote? Via @PJDunleavy https://t.co/qMdx9Lztog https://t.co/aXdsvr6kWQ

RT @SusannaRustin: Parish councils can empower local communities, but we need more of them in cities writes @richard3berry https://t.co/Q0N1…

I’m one of the Queen’s Park cllrs who stood unopposed in May. Thanks very much for writing this very good article. I just wanted to add that the non-party-political nature of our council is relevant in terms of how our first elections turned out. We were all independent candidates, with no party backing, and contested elections between local people without any clear (or stated) political differences are – we discovered – a sensitive business, as people are being elected for who they are, and on their track record locally, rather than which party or set of ideas they represent. We hope more candidates will come forward next time but I also agree that the number of candidates is not the only test of a parish/community council – the number of residents the council manages to engage in its activities is another test, as is the turnout. Loads more work to be done there.

Thanks for the comment Susanna, and for tweeting the article too. And congratulations on getting the council up and running. I hope the reference to uncontested elections is not taken as a criticism by you and fellow councillors. As I said in response to an earlier comment I don’t think this is necessarily a problem for a community council, and the relatively high turnout is a big positive. There are lots of people including myself who will be interested to see how Queens Park develops as a model for others over the next few years.

If interested in really local democracy, perhaps a rethink of ‘more tea, vicar’ image of Parish Councils is needed https://t.co/rFx1j9oLwF

Welsh Government have been thinking through some similar issues at the moment. My own view is that the answer is to strengthen the role of local councillors as ‘mini mayors’ https://localopolis.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/71-mini-mayors.html

We need parish councils in cities to counteract the remoteness of UK local government https://t.co/gquPr1AOH5 https://t.co/CWCIfxE3Ye

You’re right to draw attention to the fact that principal local authorities in the UK are not all that local, and in fact all the pressure is towards making them larger and even less local. We have not yet solved the dilemma: efficiency and effectiveness of services require a large population, but this means the authority doesn’t represent anything which its residents recognise as local.

While half of Queen’s Park was unopposed, it did better in having contested elections than most parish councils do. Very few have more candidates than there are seats when the regular election cycle comes round, and most casual vacancies (unlike in the novel) are filled by co-option rather than byelections. This is a sort of democratic deficit.

Incidentally parishes strictly speaking have no responsibilities – there is nothing they have to do by law.

Thanks for the comment, David. The point about contested elections raises an interesting discussion. How vital is contestation? In very small communities, perhaps it is not necessarily undemocratic if certain people come forward as community leaders while others decide to let them lead without opposition (as long as there is always the possibility for them to be opposed). I have criticised NHS Foundation Trusts on the basis that 50% of their governor elections are unopposed, but these are institutions covering very wide areas and large populations – if not enough people come forward it’s because not enough of them want to participate.

“We need more parish councils in cities” – https://t.co/FaN56K5n4h – via @democraticaudit

Parish councils can empower local communities, but we need more of them in cities https://t.co/KIaRvIlWKT