Women legislators create higher levels of political engagement amongst women constituents

In less than thirty years, women’s representation in the Senate has gone from two to twenty. In new research, Kim L. Fridkin and Patrick J. Kenney look at how this shift has influenced people’s understanding of, and engagement in, politics. Using election survey data, they find that women constituents tend to know more about their senators than males and that they are also more likely to be politically active if their senator is a woman.

Credit: Neon Tommy, CC BY ND 2.0

Today, 20 women serve in the U.S. Senate, representing large states, small states and states from every region of the country. Women senators represent approximately 125 million citizens in the U.S. Senate, nearly 40 percent of the U.S. population. The U.S. Senate, in light of its unique powers over treaties, ambassadorial appointments, Supreme Court appointments, length of terms, and the absence of term limits, is arguably among the most powerful legislative chambers in the world.

On the eve of the 2014 senatorial elections, four women senators are running for reelection in Maine, North Carolina, Louisiana, and New Hampshire. In nine other states, women candidates are competing as challengers or running for seats being vacated by retiring male senators. While many of these contests are competitive, including several races with women senators, we expect that the number of women serving in the U.S. Senate will hold steady or increase slightly after the 2014 elections.

The shift in the gender profile of U.S. Senators has been swift. In 1986, less than thirty years ago, only two states sent women to the U.S. Senate, Maryland and Kansas, representing a tiny fraction of all Americans. Has the dramatic change in the gender composition of the U.S. Senate influenced people’s understanding and engagement in politics? In particular, do constituents know more about their women senators, compared to their male senators? And, does the gender of senators influence people’s level of engagement in politics? In new research, we find that women senators mean that women in the electorate are more likely to be politically active, and know more about their senators as well.

To examine whether people know more about men or women senators, we test two rival hypotheses. The novelty hypothesis predicts both men and women in the electorate will know more about women senators, compared to men senators. According to the novelty hypothesis, women senators will stick out because people expect senators to be men given their gender stereotypes and the small number of women who have served historically in the U.S. Senate. We know from research in cognitive psychology that information that is unexpected or novel, like women senators, cannot be processed automatically. Instead, the novelty hypothesis predicts that people will need to rely on conscious processing and engage in more effortful behavior when attempting to interpret news about women senators. This behavior is expected to produce greater recall of processed information about women senators compared to information obtained about less salient male senators. Therefore, all things being equal, the novelty hypothesis predicts that both men and women in the electorate will know more about women senators than men senators.

In contrast, the saliency of self hypothesis predicts women citizens will be affected more powerfully by the novelty of women senators. According to this hypothesis, the novelty of women senators will prime women citizens with “self-relevant” information (e.g., information related to one’s self-concept), thereby powerfully affecting information processing for these women citizens. That is, women senators will be particularly relevant to women citizens, producing a greater impact of the gender of the senator on political knowledge for women compared to men in the electorate.

We also look at whether the gender of U.S. Senators influences people’s engagement in politics. In particular, we hypothesize that women senators will uniquely mobilize women in the electorate for two reasons. First, women and men often have different policy priorities and women in elective office send a signal to women citizens that their priorities will be represented more forcefully and accurately. Second, women in government may produce symbolic benefits, sending messages to women citizens that politics is open and inclusive.

To explore these questions, we utilize the 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Survey (CCES) to explore citizens’ assessments of their U.S. Senators. Respondents were interviewed in October and then re-interviewed in November after the 2006 election. Respondents completed the survey on the Internet, answering a series of questions assessing their views about politics and political figures as well as their attitudes about variety of political issues. The 2006 CCES contained a large sample of 36,500 respondents.

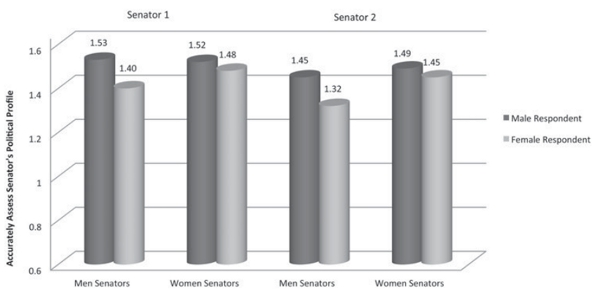

We look at whether people’s ability to answer relatively easy (e.g., identify the party and the ideological position of senators as shown in Figure 1) and more difficult questions (the correct roll call votes of senators) varies with the gender of the senator. We find support for the saliency of self hypothesis. We find the gender of the senator significantly increases women citizens’ ability to answer easy and difficult questions about women senators, compared to male senators. In contrast, for male citizens, the gender of the senator did not significantly influence their ability to accurately answer questions about their senators. In examining the impact of the senator’s gender on people’s level of information about their senators, we make sure to control for a series of rival explanations, including the seniority of the senator and the political sophistication of citizens.

Figure 1 – Senators’ and Respondents’ Gender and their Ability to Accurately Assess Senator’s Political Profile

To explore whether the gender of the senator mobilizes women in the electorate, we constructed a political engagement index based on a series of questions including whether citizens voted in the election, gave money to a political candidate, tried to persuade someone to vote for a particular candidate, and whether citizens said they belonged to a political group. We control for a number of considerations correlated with political participation, such as the competitive nature of the senator’s election campaign and people’s level of political interest. We find the gender of the senator has a positive and significant impact on women in the electorate and leads to greater levels of political activity for women represented by women senators. In other words, women senators lead to higher levels of political engagement for women constituents.

We expect that increases in the number of women being represented by women senators will encourage women in the electorate to become more informed and more engaged, leading to increases in the number of women being elected to the U.S. Senate as well as other local, statewide, and national offices. Furthermore, if the much-rumored candidacy of Hillary Clinton for president in 2016 actually happens, this campaign may serve to significantly empower women citizens, especially if her campaign is successful.

—

Note: This article originally appeared on the LSE USApp– American Politics and Policy blog. It represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit nor of the London School of Economics. This article is based on the paper ‘How the Gender of U.S. Senators Influences People’s Understanding and Engagement in Politics’ in the Journal of Politics. Please read our comments policy before commenting

—

Kim Fridkin is a Professor of Political Science at Arizona State University. Her current research interests are negative campaigning, women and politics, and senate elections.

Kim Fridkin is a Professor of Political Science at Arizona State University. Her current research interests are negative campaigning, women and politics, and senate elections.

Patrick J. Kenney is the Vice Provost and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Dean of Social Sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the Director of The Institute for Social Science Research at Arizona State University. He has co-authored three books with Kim Fridkin, The Spectacle of U.S. Senate Campaigns (Princeton Press, 1999), No-Holds Barred: Negativity in U.S. Senate Campaigns (Prentice Hall, 2004) and The Changing Face of Representation (University of Michigan Press, 2014).

Patrick J. Kenney is the Vice Provost and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Dean of Social Sciences in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the Director of The Institute for Social Science Research at Arizona State University. He has co-authored three books with Kim Fridkin, The Spectacle of U.S. Senate Campaigns (Princeton Press, 1999), No-Holds Barred: Negativity in U.S. Senate Campaigns (Prentice Hall, 2004) and The Changing Face of Representation (University of Michigan Press, 2014).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

MT @dmch010: more women politicians = more women interested in political activity? Sounds good. https://t.co/Q6rc5ltH5A #ncpol

more women politicians = more women interested in political activity? Sounds good. https://t.co/TV8NiVKIM1 #ncpol @democracync

Huh, interesting > MT @democraticaudit: Women legislators increase political engagement in women constituents https://t.co/OE1Xbw8AFu

Does the presence of women representatives increase political engagement amongst women? https://t.co/6RrxR3WRKI

#PL2021 “@democraticaudit: Does the presence of women representatives increase political engagement amongst women? https://t.co/zyKitCgCoB”

Women legislators create higher levels of political engagement amongst women constituents https://t.co/lvlEH4f1sn https://t.co/JstDHKPCgd

Women legislators create higher levels of political engagement amongst women constituents https://t.co/kPWSGAYdOg