Perception is key in explaining when election results are, and aren’t, accepted by voters

Is it sufficient for elections merely to have been conducted fairly for the result to be accepted? Drawing on research conducted on 28 separate elections, Miguel Angel Lara Otaola argues that elections not only need to be conducted fairly, but that they have to be perceived as such. If this does not happen, the risk of violence and other kinds of instability is heightened considerably.

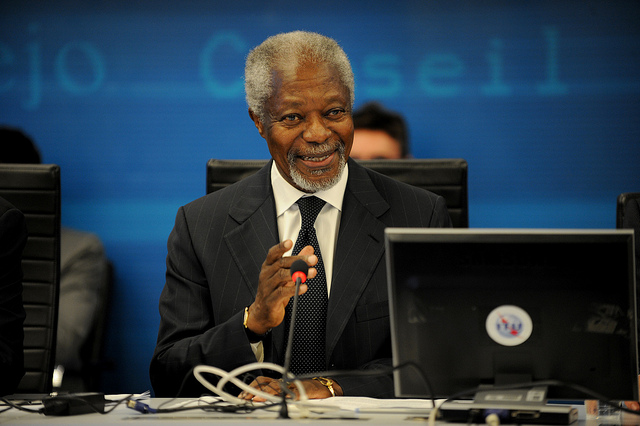

Credit: ITU pictures, CC BY 2.0

“When the electorate believes that elections have been free and fair, they can be a powerful catalyst for better governance, greater security and human development. But in the absence of credible elections, citizens have no recourse to peaceful political change.” (Kofi Annan, 2011)

Having credible elections is highly important. Elections that are accepted by citizens and political parties are critical for having a strong democracy and contribute to national stability. However, when elections are not accepted, they weaken trust in the political system and can threaten peace and security. This is especially true in new democracies.

Sometimes, when elections and their results are rejected they can bring about conflict and violence in the form of post-election protests. A good example of this is the 2004 presidential election in Taiwan, where after a “photo-finish”, the pan-blue alliance called fraud and organised mass protests that included sit-downs, demonstrations, riots and blockades. Moreover, unaccepted elections can be the spark that ignites other non-election related issues and set alight deep rooted grievances. In the 2007 presidential election in Kenya, election related problems led to protests which were soon followed by ethnic violence against the Kikuyu group, costing more than 1,000 lives and hundreds of thousands displaced.

Normally, protests are expected to erupt in countries where elections are systematically rigged and voters have no choice. But what about democratic countries -and elections considered as “free and fair”- that end up with highly disputed results, mass demonstrations and/or riots? Conventional wisdom holds that if elections are technically accurate and “free and fair”, they should be accepted by citizens and political parties (Here, the acceptance of election results is understood as the lack of post-election mass protests held as a way to challenge the results.) However, empirical reality shows that this is not always the case. So, when, where and under what conditions are electoral results accepted?

My research suggests that technical accuracy in election administration is not enough for the acceptance of election results. Elections not only have to be free and fair but also perceived as such. Especially in emerging democracies, where citizens and political parties have only experienced a few electoral contests, technical accuracy needs to happen in combination with other factors.

I first test the impact of technical accuracy on the acceptance of results. An election can be identified as ‘technically accurate’ in a “free and fair” sense where international standards for election administration have been met fully or mostly. Three other key conditions also matter. The first one is the overall support for the political system by citizens. This means that individuals believe the system and its institutions are legitimate, even though they might disagree with some of its decisions. The second is the support of political parties for institutions of electoral administration. This refers to the acceptance by political parties of the electoral management institution and its top managers. The third is the provision of clear and transparent election results. Results must be accurate and clearly communicated and open to citizens and political parties.

I have tested the importance of these four conditions in all presidential elections with close results between 2000 and 2014. In total, I analysed 28 elections in 20 emerging democracies in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America. For doing so, I employed crisp set Qualitative Comparative Analysis, a comparative method which helps identify and explain the necessary and sufficient conditions that lead to a specific outcome, in this case the acceptance of election results.

Results demonstrate that three of the four conditions analysed play an important role in supporting the acceptance of election results. The path that leads to the acceptance of election results is a combination of political party support, technical accuracy and clear and transparent election results (The condition of system support is not relevant, which means that both a low and a high level of system support can lead to the acceptance of results.) According to the QCA analysis, individually all of these three conditions are necessary for the acceptance of results. However, by themselves, none of them are sufficient. Together, they are necessary and sufficient.

So, on its own, having a well-managed election does not assure that results will be accepted. A good example of this is the 2006 presidential elections in Mexico. Here, an internationally acclaimed electoral management system and an electoral process described as efficient, very well organized, transparent and clean resulted in months of street protests led by a candidate that claimed to be Mexico’s “legitimate president”. This happened because of the lack of support of one of the main political parties to the General Council of the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) and by the confusion created by the poor communication of election results.

Even if all or most aspects of an election (such as voter registration, the registration of candidates and parties, campaigning, the training of polling staff and Election Day logistics and polling) are procedurally sound, there are still other not so technical factors at play. These are related to the realm of perception and are equally important. After all, one must bear in mind that, as international election expert Johann Kriegler put it “Elections are not about mathematics, elections are not about law. Elections are about people, about perceptions, about beliefs”. Having a technically accurate election is not enough for the acceptance of election results; it must happen in combination with the support of political parties and clear and transparent election results.

—

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Miguel Angel Lara Otaola is a PhD Research Student at the University of Sussex. His research question is “When, where and under what conditions are electoral results accepted?: A global comparative study”

Miguel Angel Lara Otaola is a PhD Research Student at the University of Sussex. His research question is “When, where and under what conditions are electoral results accepted?: A global comparative study”

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Perception is key in explaining when election results are, and aren’t, accepted by voters : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/x81SA1PzDa

RT @democraticaudit: Perception is key in explaining when election results are, and aren’t, accepted by voters : Democratic Audit UK http:/…

Perception is key in explaining when election results are, and aren’t, accepted by voters https://t.co/VmTMHdN7VS https://t.co/UUJjCGCLWy

Interesting article by @malaraotaola from @SussexUni on why perception of fair conduct in elections is so important: https://t.co/yndDxA25dO

Perception is key in explaining when election results are, and aren’t, accepted by voters https://t.co/dcfRdeP01X