Revenge porn should be treated not as a scandal, but as the sex crime it is

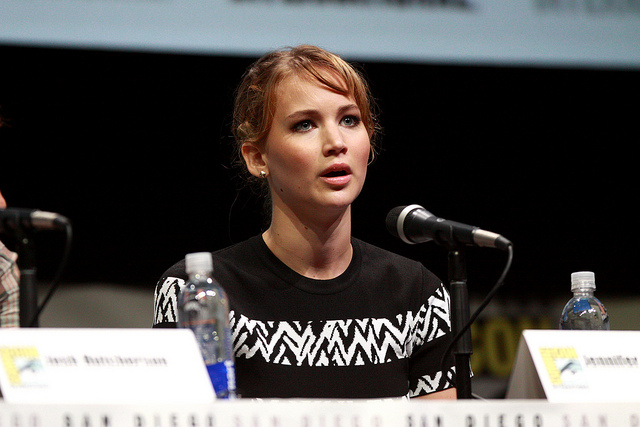

Recent months have seen the publication of nude pictures of Jennifer Lawrence among other celebrities, with the actor describing their appearance as a sex crime. Laura Hilly agrees, and argues that the UK government should move swiftly to ensure that incidences like this, and ‘revenge porn’ more widely are treated as the crime they are, and hopes that the devil in the detail does not prevent any new laws from effectively preventing this modern variant of sexual violence.

International headlines were made in August when hackers stole from private devices and online accounts naked images of celebrities such as Jennifer Lawrence, Rihanna and Kate Upton and published them for the world to see. This intrusion shines a spotlight on a growing form of gender-based violence: revenge porn. Age-old misogynistic exploitation of women’s bodies and shaming female sexuality is re-fashioned for the digital age. Legislative reforms are to be introduced in the UK, but are they enough to really see revenge porn for what it is: a sex crime?

Revenge porn involves the distribution of explicit photos or videos of individuals without their consent. These images are usually consensually created and shared with a partner during the course of a relationship.However, when the relationship turns sour, disgruntled ex’s have taken to the internet in order to try and shame and embarrass their ex-lovers. This practice is frighteningly common. Recent statistics suggest that one in ten ex-partners threaten to post sexually explicit images of their former partner online, and 60% of these actually go through with it. The UK Safer Internet Centre has identified between 20 and 30 websites displaying revenge porn available in the UK. This is also a particularly gendered wrong – as many as 90% of all victims of revenge-porn are women.

Lawrence, in responding to the online publication of these images was clear on how this violation should be characterized: ‘it is not a scandal. It is a sex crime…It is a sexual violation. It’s disgusting. The law needs to be changed, and we need to change.” Up until now, victims in the UK have been able to seek limited redress for the harm caused through current laws, ranging from actions against perpetrators for harassment, communications offences, blackmail and voyeurism. However, expert practitioners note that ‘the law does not provide easy answers’ and ‘stronger legal tools are needed’.

Fortunately, for those in the England and Wales (and Scotland hopefully soon to follow), enhanced legal protection may be imminent. On 20 October 2014 the House of Lords debated a new offence, punishable with up to two years’ imprisonment, criminalizing the disclosure of photographs or films which show people engaged in sexual activity or depicted in a sexual way, where what is shown would not usually be seen in public. For the offence to be committed the disclosure must take place without the consent of at least one of those featured in the picture, and with the intention of causing that person distress.

However, there were suggestions that the new laws do not go far enough. Baroness Thornton highlighted that the requirement that the publication causes or intends to cause ‘distress’ is problematic. Will the new law provide a remedy for victims who are not distressed by the publication, but angry? Does the inclusion of the word ‘distress’ send a broader message, that the only valid response to such publication should be distress? Does this reinforce the shaming of female sexuality and stigmatize women who, as was the case for Lawrence, have no desire to apologise for their decision to take the private photographs in the first place? Furthermore, would the requirement of an intention to cause distress be capable of capturing situations where the images are motivated by purely by commercial gain?

Experts in the field contend that ‘the mental element of the offence should be the intentional act of posting private sexual images, without consent, including for the purpose of financial gain.’ This formulation more closely mirrors that adopted by other jurisdictions. For instance, in Australia, Victorian legislation passed earlier this month criminalizes conduct where a person intentionally distributes, or threatens to distribute, an intimate image of another person and the distribution of the image is contrary to ‘community standards of acceptable conduct.’ This formulation has the potential to provide more comprehensive protection to those falling victim to these practices.

Finally, why won’t the new law be characterised as a sexual offences? Lord Faulks opined that ‘we do not think that it is appropriate to view it as a particular sexual offence in the same way as (an offence under the Sexual Offences Act 2003). Research in previous cases has shown that “revenge” porn is perpetrated with the intention of making a victim feel humiliated and distressed rather than to obtain sexual gratification, which is what defines an offence as sexual.’ This characterisation is suspect, as feminist scholars have long emphasised that sexual offences often have more to do with power than sex, in the same way that the distribution of revenge porn clearly does.

The draft provisions are generally a welcome development, but hopefully the devil in the detail will not prevent these new laws from being an effective tool to combat this new and noxious form of gender-based violence.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the Oxford Human Rights Hub blog and is reposted with permission. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

From our archive: Revenge porn should be treated not as a scandal, but as the sex crime it is https://t.co/VVgWfFk9ze

‘Revenge porn should be treated not as a scandal, but as the sex crime it is’ (via @democraticaudit) https://t.co/iFf85j7exA

Revenge porn should be treated not as a scandal, but as the sex crime it is https://t.co/op7ceIozYU

Revenge porn should be treated not as a scandal, but as the sex crime it is https://t.co/QNdMN6BW3J