The emergence of lucrative post-Prime Ministerial and Presidential business careers raises questions which go to the heart of democracy

Political leaders used to either retire or remain engaged in the political sphere after their executive careers are over. However, a number of factors, including the younger age at which political careers end, has led to the development of a new trend in which former leaders earn enormous amounts of money in the private sector. Fortunato Musella argues that this has implications for democracy, with political leaders potentially deprived of agency due to the expectation of future careers in business.

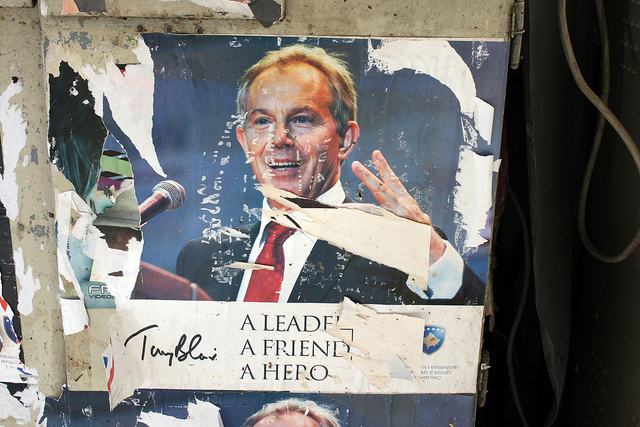

Credit: CC BY SA 2.0

Executive leaders in several contemporary democracies have something in common. Until recently, the office of the President or Prime Minister represented the zenith of a high-level political career, and the strongest ambition of long term politicians who spent great part of their life in institutional or party activities. In recent years, however, career paths do not end with politics but instead continue into business. Former British Prime Minister, Tony Blair is probably the most notable example of this new career route. In fact, after leaving Downing Street, Blair became a consultant at JPMorgan Chase Bank on a salary of over £2 million a year. He also has links with a Korean oil company with significant interests in Northern Iraq, the UI Energy Corporation, and has delivered a number of well-paid lectures round the world. So it is no surprise that he now declares earnings of around £12 million.

More surprising still is that Blair is not an isolated case on the international stage. On the contrary, as my recently published empirical analysis in European Political Science Review shows, by examining a dataset of 441 leaders in 78 different democratic countries over a period dating from 1989 to 2012, former presidents and prime ministers often begin in politics but end up in the world of business or international finance.

This occurs more and more than in the past. And the phenomenon regard many countries, from Northern America to Germany and Spain, from Australia to Israel. In the United States, John and George W. Bush looked after the finances for the Carlyle Group. Mulroney became a consultant for Ogilvy Renault after leaving the office of prime minister in Canada, and he is a board-member of many international firms. Josè Maria Aznar went from being Spain’s Head of Government to joining the board of News International. Bob Hawke, on the other hand, is making a fortune selling Australian land to the Chinese. Israeli leaders from Netanyahu to Olmert have followed in their footsteps, and even Barak, after being a partner in an American finance firm, founded his own company which is called after him, the “Ehud Barak Limited”.

Party involvement is still crucial for entry in politics, and parliamentary activity is an absolute pre-requisite for achieving ministerial and prime ministerial office: analysis of data confirms that if we look at the highest positions in government, politicians have careers within politics in 85.4% of cases, whereas only 5% of leaders come to power as a result of their business or entrepreneurial affairs.

Yet The relationship between politics and business becomes much closer after the presidents leave the office. The fact that leaders are now younger when they retire reinforces this trend (more than 40% of presidents and prime ministers take over the leadership of the national executive before they are fifty), they are also much more active after their presidential mandate. Post-executive lives are very often far from the image of “dormant volcano”, which referred to those leaders who prefer to go home after reaching the pinnacle of the political system, and having fought numerous political battles. New former leaders use their political experience – and influence – to engage in international or supranational roles, act as international emissaries for humanitarian causes or human rights, or giving support to candidate they favour in national politics.

The true novelty is represented, however, by the diffusion of the phenomenon of those former leader who live a “second act” of their career destined to business. They are who in the EPSR I describe as “presidents in business”. It may be estimated that 21.4% of post-presidential roles are in the area of business and consultancy. When one considers that the most famous analysis of presidential career simply ignored the phenomenon until a few years ago, this is extraordinary. The new pattern is also significant from the point of view of democratic theory, given that world leaders may use their executive mandate in order to gain entry into new positions. Consider for instance the case of the former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who was one of the most outspoken supporters of a new viaduct to transport gas from Russia to Germany while in office, and once he left government, he was given a directorship in the company Gazprom, responsible for building that same viaduct. He has been a member of the multinational petroleum company TNK-BP since 2009 too.

New links between democratic governments and business are changing the nature, and the perspectives, of representative regimes. Indeed, what a politician considers as a future aspiration also influences his activities in office, and the way in which he acts and interacts with other social actors. The logic of democratic representative systems supposes that the electorate are able to influence those they elect, and representatives tend to respond to citizens with a certain degree of independence from corporate business. Yet the emergence of a career path which leads directly from politics to business, rather to be only a free personal option for world leaders, goes at the heart of democracy. Whose continued functioning and survival remains related to the autonomy of its leaders.

—

This article is based on the research “Presidents in business. Career and destiny of democratic leaders“, in European Political Science Review, 2014, Published online: 13 June 2014.

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Fortunato Musella Phd in Political Science of the University of Florence, he is currently Professor of Political Science at the University of Naples Federico II and Professor of Political Concepts in the PhD programs of the Scuola Normale di Pisa. He is also member of the Executive Committee of the Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica. His main research interests include the study of government, presidential politics, political parties, and concept analysis. Among his recent publications the volumes Governi monocratici. La svolta presidenziale nelle regioni italiane (Il Mulino 2009) and Il premier diviso. Italia tra presidenzialismo e parlamentarismo (Bocconi 2012), and about fifty book chapters and articles published in peer review journals such as European Political Science Review, Representation, Contemporary Italian Politics.

Fortunato Musella Phd in Political Science of the University of Florence, he is currently Professor of Political Science at the University of Naples Federico II and Professor of Political Concepts in the PhD programs of the Scuola Normale di Pisa. He is also member of the Executive Committee of the Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica. His main research interests include the study of government, presidential politics, political parties, and concept analysis. Among his recent publications the volumes Governi monocratici. La svolta presidenziale nelle regioni italiane (Il Mulino 2009) and Il premier diviso. Italia tra presidenzialismo e parlamentarismo (Bocconi 2012), and about fifty book chapters and articles published in peer review journals such as European Political Science Review, Representation, Contemporary Italian Politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Tony Blair isn’t alone in turning his political and governmental expertise into hard cash. But this new trend poses genuine questions for democracy, according to Fortunato Mussella for Democratic Audit UK. Find out more here. […]

The emergence of post-executive leadership business careers raises questions which go to the heart of democracy https://t.co/cN9Ju888BD

“21.4% of post-presidential roles are in…business&consultancy.” Democratic threat? asks @foMusella @democraticaudit https://t.co/Cfv2Y70F5w

Remember how #Labour’s “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich”? #TonyBlair’s showing us how its done! https://t.co/gWX1kHhlDB

What Tony Did Next. And how it reflects on leadership and democracy: https://t.co/73UzEPDeWw

Lucrative post-office business careers raises questions which go to the heart of democracy https://t.co/LMjXt4hltR https://t.co/nZrwegQtt3

The emergence of lucrative post-Prime Ministerial and Presidential business careers raises questions which go to… https://t.co/wQjOuOT18w