Tackling political inequality requires a “carrot and stick” approach

The UK’s political and democratic system are under severe strain, with declining turnout and increased apathy threatening the legitimacy of the current constitutional settlement. Mathew Lawrence and Glenn Gottfried argues that in order to do something about it, new deliberative and experimental institutional forms of democratic life must be combined with the introduction of first time compulsory voting.

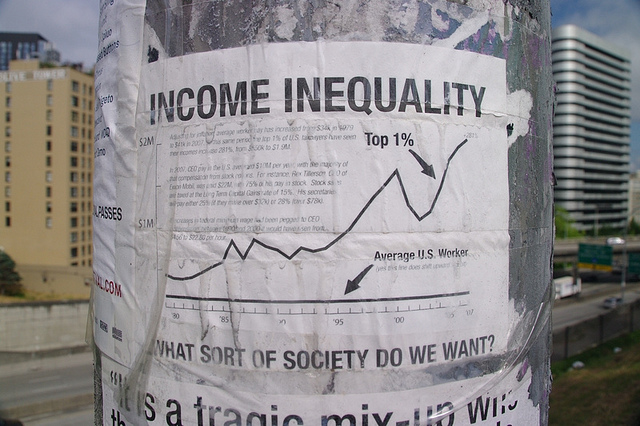

Credit: mSeattle, CC BY 2.0

Yesterday, the BBC celebrated Democracy Day, marking the 750th anniversary of De Montfort’s first English parliament. Yet despite the self-congratulations, parliamentary democracy is presently experiencing a period of sustained, traumatic erosion in its legitimacy: falling levels of participation in formal politics, the fragmentation of old political identities, a decline in the public’s belief in representative model. Put simply, Western democracies are hollowing out.

New IPPR polling shows just how detached the public has become from the way British democracy functions. When asked how well they believed British democracy addressed their interests only 38% said ‘well’ compared to 53% who said ‘not well’. There is also a deep class divide in this sentiment. When analysing the same question almost half of all those who fit within the AB social class believe British democracy serves their interest. This is a sharp contrast to those within the working class (DE) amongst whom only 1 in 4 say Britain’s democracy addresses their interests.

For too many, democracy appears a game rigged in favour of the powerful and the well-connected, with the political process distant from ordinary life or unable to take substantive decisions that run against particular interests. In a seemingly neutered democracy, populism has surged and a deeply political ‘anti-politics’ mood emerged. Underpinning this is the rise in political inequality, where despite procedural democratic equality, certain individuals and organisations have far more influence over the political decision-making process. For example, under the “strategic relations” initiative 80 corporations have been granted a ‘ministerial buddy’ within government, giving them privileged access to the political decision-making process.

Of course, no democracy has existed where certain individuals or organisations have not had greater access, influence or political resources than others, whether because of gender or racial discrimination, or class structures. But in the post-war era a set of institutions and practices sustained the legitimacy of the system and in some ways allowed for more equal levels of influence within it; mass parties, broad-based political participation, settled class structures, identities and organisations like trade unions or the Church of England, and an effective electoral duopoly by Labour and the Conservatives, for example.

As those countervailing forces or institutions have withered, political and economic power has gravitated away from democratic institutions and the electorate, towards undemocratic institutions and insulated elites, less amenable to influence by popular democratic pressure.

The challenge now in reversing political inequality is to revive what is necessary of the old democratic order – broadly based political parties and other institutions of collective voice, and large-scale political participation in formal and informal politics – while experimenting with new forms of democratic voice and influence in the political system. As technology breaks down old hierarchies, new ways of participating and organising political life are possible if pursued with patience. Combined with more participatory, deliberative and experimental institutional forms of democratic life, there is the potential for a more responsive, broad-based and legitimate democracy to emerge.

There’s needs to be a stick too: first time voting should be compulsory, with a choice of “none of the above”, in order to institute the voting habit at the start of adult life, and expand the political influence of the young. This is not any more illiberal than asking people to perform the civic duty of jury service. Our individual liberties rest on a democratic political order that we have to sustain.

It won’t be easy. However, it is a much surer bet for reviving our democracy than complacency.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Glenn Gottfried is Quantitative Research Fellow at IPPR

Glenn Gottfried is Quantitative Research Fellow at IPPR

Mathew Lawrence is Research Fellow at the IPPR

Mathew Lawrence is Research Fellow at the IPPR

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Hauria de ser obligatori votar la primera vegada pels joves que fan 18 anys? Una idea interessant a @democraticaudit https://t.co/m1suVh8rNM

READ >Tackling political inequality requires a carrot&stick approach >@GGottfried1& @DantonsHead on @democraticaudit https://t.co/DdQOCmQ0P6

Tackling political inequality requires a “carrot and stick” approach say G. Gottfried & M. Lawrence of the @IPPR https://t.co/QPdzTQkB3w

Reviving parliamentary democracy requires going beyond parliamentary democracy – new @IPPR blog at @democraticaudit: https://t.co/3LfmKgReeK

Tackling political inequality requires a “carrot and stick” approach https://t.co/Q2niroMG9Y

Reformed institutions and 1st time compulsory voting can tackle political inequality. @IPPR blog at @democraticaudit: https://t.co/8xHLVpxEQy

Tackling political inequality requires a “carrot and stick” approach https://t.co/wgGCtM184j