There has been a substantial drop in EU legislative output since 2010

A common argument made against the European Union by Eurosceptic politicians is that the EU creates a burden on citizens and businesses by producing too much legislation. But how much legislation does the EU actually produce? Renaud Dehousse and Olivier Rozenberg present data on both the raw number of EU acts adopted since 1996, and a measure of the burden produced by this legislation. They note that contrary to expectations, there has been a substantial fall in the EU’s legislative output since 2010, raising questions over the motivations underpinning the European Commission’s legislative agenda.

Credit: Michael Sanger, CC BY NC SA 2.0

Last December, the European Commission proposed a legislative agenda that differed significantly from previous submissions. It mentions only 23 new initiatives, of which 14 contain a legislative component. On the other hand it lists 83 proposals that will be abandoned or amended. By way of comparison, the work programme for 2013 (the last ‘full’ year before the European elections) referred to 53 new initiatives, of which 39 contained a legislative component along with 14 withdrawals.

This change of course is in no way accidental; in fact it is declared resolutely in the explanatory statement, which mirrors the language used by Jean-Claude Juncker during his inaugural speech: “Citizens expect the EU to make a difference on the big economic and social challenges… they want less EU interference on the issues where Member States are better equipped to give the right response at national and regional level…That is why we will focus on the ‘big things’ like jobs and growth.” The Commission indicates for that matter the willingness to “reach out beyond the Brussels base across the EU” and explains its sizable programme of withdrawals with a willingness to “[lighten] the regulatory load” and especially regarding environmental protection, in which Europe plays a leading role.

This declared will in favour of reconditioning would be more convincing if it didn’t sound a little too familiar. José Manuel Barroso was already saying in 2013, while presenting his own programme of reduction of regulatory constraints (REFIT), that Europe should be “big on the bigger things, small on the smaller things”. In addition, nearly 20 years ago, Jacques Santer held the motto, “do less, but better”. This repetition could be seen as confirmation that the successive Commissions are incapable of overcoming the bureaucratic Hydra, regularly depicted by the British tabloids, according to whom the bureaucrats in Brussels put all their energy into regulating even the most minute aspects of our lives. It is true that the First Vice President, Frans Timmermans, the great architect of this new course, held a similar position as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Netherlands…

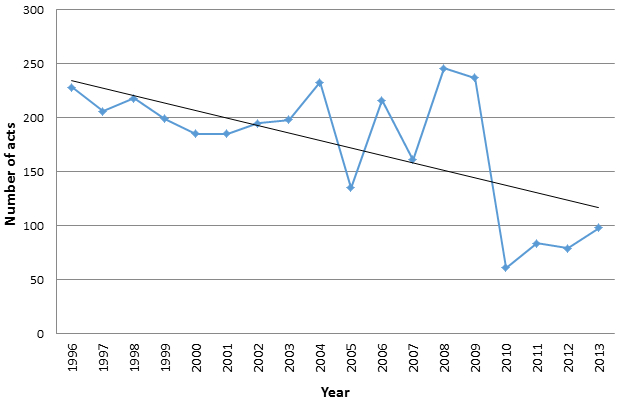

In reality, the situation is less exaggerated. Consulting the official minutes of the Council, one will notice that the European legislative output, which has been relatively stable for many years, dropped suddenly during the last term. Chart 1 below shows the reduction in outputs, which is proportional across all types of legislative acts (regulations, directives, and decisions).

Chart 1: Number of adopted EU acts by year (1996-2013)

Source: EU Legislative Output 1999-2013 [database], Centre for Socio-political Data (CDSP, CNRS – Sciences Po) and Centre d’Etudes Européennes (CEE, Sciences Po) [producers], Centre for Socio-political Data [distributor].

It also been established elsewhere that the common belief that as much as 80 per cent of national legislation comes from Brussels is merely a myth: the transposition of directives only makes up between 10 per cent and 30 per cent of the activity in national parliaments, depending on the country in question. In fact, for a more precise idea of the weight of regulatory constraints, it is necessary to do more than simply count the number of texts.

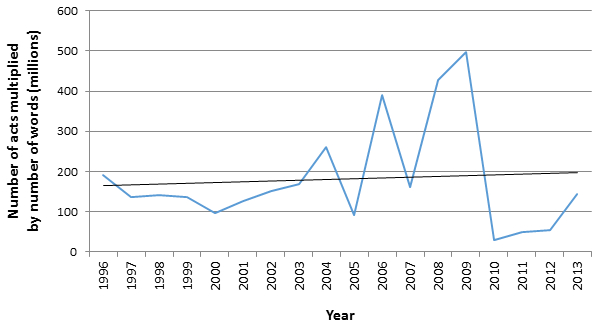

In certain countries, such as France or the UK, the apparent stability concerning annual domestic legislative output hides the lengthening of texts that are adopted. In order to detect a potential phenomenon, we have produced an index of legislative constraint, multiplying the number of texts by their word count. Chart 2 below illustrates the result. It reveals a slightly different dynamic; there is certainly an overall trend in the lengthening of texts, reaching a peak during the first mandate of José Manuel Barroso, however this does not erase the sudden break that occurred in 2010.

Chart 2: EU legislative burden by year (1996-2013)

Source: EU Legislative Output 1999-2013 [database], Centre for Socio-political Data (CDSP, CNRS – Sciences Po) and Centre d’Etudes Européennes (CEE, Sciences Po) [producers], Centre for Socio-political Data [distributor].

The fall in legislative output shown by this data is not easy to interpret. Is it due to the economic crisis, which would have required all the energy of the European institutions and at the same time reduced the attention given to other questions? Is it because of a more difficult political context, marked by a loss in public confidence in Europe and by the rise in populism, which reduces national governments’ willingness to compromise? Or the consequence of successive reforms to the comitology process, which have strengthened the powers of the Commission in matters concerning the adoption of implementing standards for regulatory texts? All these hypotheses require closer examination. Moreover, this aggregated data can hide substantial variations from one area to the other.

As such, however, the data above leads us to question the motivations of the Commission. Why take on – and hence validate – a widespread position on the thirst for power that Europe would show? Is it because the Commission is unaware of the developments over recent years – hard to believe in our opinion – or because it intends to send signs of goodwill to national governments that complain about Europe’s regulatory activism? However, does the Commission really have much to gain in running after David Cameron, who in turn is running after Nigel Farage – with the success that we all know?

—

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. It originally appeared on LSE Europp – European Politics and Policy. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Renaud Dehousse holds a Jean Monnet Chair in European Union Law and Political Science and is Director of the Centre d’études européennes at Sciences Po.

Renaud Dehousse holds a Jean Monnet Chair in European Union Law and Political Science and is Director of the Centre d’études européennes at Sciences Po.

Olivier Rozenberg is Associate Professor in the Centre d’études européennes at Sciences Po.

Olivier Rozenberg is Associate Professor in the Centre d’études européennes at Sciences Po.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

There has been a substantial drop in EU legislative output since 2010 : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/gudomUDTCy

[…] study by two academics has shown that the idea that most of our legislation comes from the EU is a […]

New @democraticaudit study shows volume of #EURedTape has fallen sharply https://t.co/IUHjlt2g6J https://t.co/oAJ56ueq7n

#EuropeanCommission | There has been a substantial drop in EU legislative output since 2010 – says @democraticaudit | https://t.co/xRKM7aa0CR

Number of EU adopted acts has fallen a lot since 1996. Economic crisis to blame? https://t.co/Wyh6J1WVYa #LSEGV101 https://t.co/PH2yjZjP2J

There has been a substantial drop in EU legislative output since 2010 https://t.co/WIsJ5ISPlN

There has been a substantial drop in EU legislative output since 2010 https://t.co/KViQ61K61f