Enough is enough: Time to regulate prime ministerial appointments to the Lords

This week the Constitution Unit publishes a new report arguing that the time has come to regulate prime ministerial appointments to the House of Lords – to prevent the chamber’s size escalating further, and prevent government manipulating its membership. The report argues that, despite large-scale Lords reform being awaited, this step is urgent ahead of the general election in May 2015. Here Meg Russell, the report’s lead author, sets out the key points.

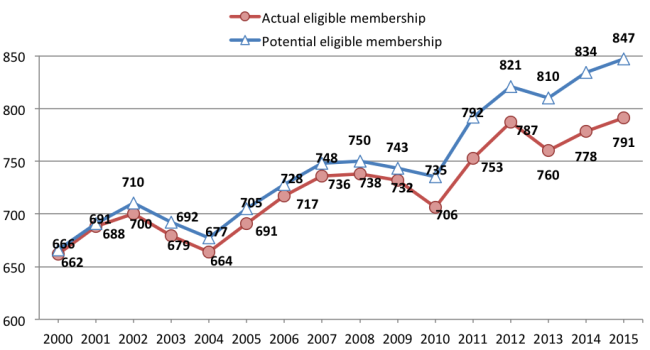

Recent years have seen endless stories about the growing size of the House of Lords (e.g. here and here). Since 1999, when the Lords was reformed to remove most hereditary peers, its membership has grown by one third – from 666 members to nearly 850 (see graph). This has caused not only media embarrassment, but concerns among the chamber’s members about its ability to function effectively. In 2013 the Lord Speaker suggested that ‘if we don’t reform and shrink our numbers, the Lords will collapse under its own weight’; last year she pointed out that debates are ‘coming under increasing time pressure as more members wish to speak, all to the detriment of our ability to hold the government to account’ (pay wall). In a full day debate on the size of the chamber last month, a former Conservative Chief Whip noted that ‘we all agree that the House cannot go on growing as it has been doing’. Yet just last weekend the Sunday Times (pay wall) claimed that a new list of up to 60 peers was likely to be announced following the general election in May 2015.

Figure 1) House of Lords membership 2000 –2015

Until recently, those supporting small incremental reforms to the Lords were focused on introducing a voluntary retirement scheme for peers. This has now happened, in the little noticed House of Lords Reform Act 2014, which started as a private member’s bill, pursued over many years by David (Lord) Steel. But to date only five peers have used the Act to permanently retire. And there is an obvious reason for this limited take-up. While appointments to the Lords remain completely unregulated, peers considering retirement risk merely weakening their group. As theHouse of Lords Leader’s Group on Members Leaving the House reported in 2011 (p. 11):

Since there is no pre-determined size for the House, and no generally-accepted understanding of the proportions in which each party and group should be represented, a member contemplating retirement could have no firm expectation that a new member of their party or group would be appointed to take their place. A member might therefore be reluctant to [retire], and there is certainly no incentive for party managers to encourage their members to retire.

Of course, there is also a more fundamental problem. Even if members of the Lords retired en masse there is no guarantee that this would succeed in shrinking the chamber – as the Prime Minister could simply appoint even larger batches of new peers. Currently the Prime Minister can appoint as many peers as he wants, whenever he wants, and with whatever balance between the parties (and Crossbenchers) he wants. He thus not only controls the size of the House of Lords, but can manipulate its membership to strengthen the government side, and thus weaken the chamber’s ability to scrutinise.

As we set out in our new report, David Cameron has made particularly lavish use of these opportunities. Since 2010 he has appointed to the Lords at a faster rate than any other Prime Minister since life peerages began in 1958 – with appointments averaging 40 per year. As shown in the graph above, while the size of the chamber grew by 69 members over the 10 years 2000-2010 under Blair and Brown, in the five years since 2010 it has grown by 112. In addition, a historic problem with the system has been that prime ministers appoint more to their own side than to the opposition or the Crossbenches. But Cameron’s appointments have been particularly skewed. Among new appointments since 2010, 62% have been to the government benches – compared to 43% under Blair, 47% under John Major and 48% under Margaret Thatcher. This unregulated party balance is a particular problem. Because each Prime Minister appoints more of their own, each change in government results in tit-for-tat action by the new Prime Minister to catch up. This has a continuous upward ratchet effect on the size of the chamber – which, of course, is also unchecked.

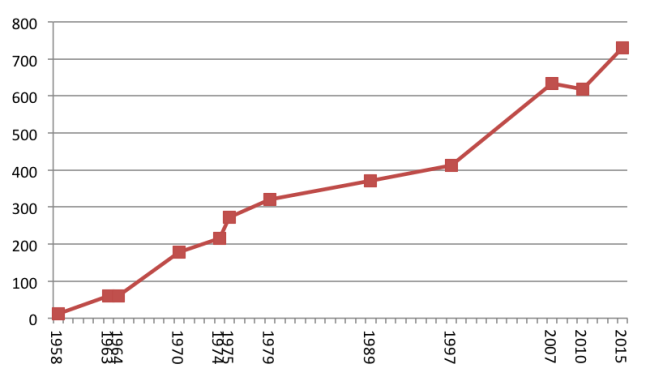

The negative effect of these trends was somewhat masked by the large numbers departing the chamber in 1999. While the graph above shows a clear increase in the size of the chamber, the numbers become even more stark when looking only at life peerages over a longer period. The first such peerages were created in 1958, and the graph below shows the growth in numbers since – with cut off points towards the end of each premiership. This depicts not the number of peers appointed, but the number alive at any one time, demonstrating a completely unsustainable rise. Numbers increased sharply under Blair 1997-2007, but the rate of increase under Cameron was even higher.

Total number of life peers 1958-2015

With the general election approaching, large-scale Lords reform is again on the political agenda. Ed Miliband has proposed a ‘Senate of the nations and regions’ to help bind the post-devolution UK together, following discussion by a constitutional convention. The Liberal Democrats also remain committed to change. But reform, if it occurs at all, will inevitably take time. The constitutional convention may not report for a year, with a further year needed for legislation. In the meantime there will be pressure for more appointments.

Several parliamentary committees have emphasised the need for a more regulated system of Lords appointments. In 2007 the Commons Public Administration Committee urged that ‘the next stage of Lords reform should not wait for a consensus on elections’ proposing that ‘the Prime Minister [should] no longer determine[s] the size of the House of Lords and the party balance’, and calling for an agreed formula for sharing out appointments (pp. 60-63). In 2013 the Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee emphasised that agreeing such a formula was the ‘most crucial’ next step in Lords reform (p. 3). But to date there has been no agreement, in part perhaps because there has been no detailed work on what a sustainable formula would look like.

Our report fills this gap. It tests in detail the effects of three alternative formulae across different election scenarios 2015-25 – looking at how they would perform under conditions of large, medium and small electoral change. A key conclusion is that the formula proposed in the 2010 coalition agreement, of bringing the balance in the Lords into line with general election votes, is completely unsustainable. In 2015 this could require the chamber to grow to 1300 members, including 150 UKIP peers. By 2025 there could be 2200 peers. An alternative formula would simply give a lead to the government party – but this creates problems by not setting out any rational basis for renewing non-government groups. The clearly preferable formula is the third one, which divides each new batch of peers fairly between the parties. Basing these (rather than the whole chamber) on general election votes would be sustainable and fair.

The report sets out some clear and hard-hitting recommendations. It emphasises that this is now the most urgent problem facing the Lords, and that it would simply be irresponsible for the new prime minister after May 2015 to continue with the existing system. Until longer-term Lords reform is achieved, a more regulated system of appointments is badly needed. The Prime Minister should extend the powers of the House of Lords Appointments Commission so that it regulates the size of the chamber, and invites nominations from the parties when vacancies arise, using a clear and transparent formula.

In the short term a target for the size of the chamber should be set – of perhaps 550 or 600. Until that target is reached, the Commission should invite nominations only on a ‘one-in-two-out’ basis, with one new peer appointed for every two that die. On present numbers that would allow about 10 appointments per year. Once this system is in place it might well be possible to make more rapid progress on retirements. If peers have confidence in how new appointments will be made, the parties might reach agreement allowing large numbers to retire. Indeed one change might be made conditional on the other. This would allow the size target to be met more quickly.

All of these changes can be made without legislation, as the current system remains wholly at the Prime Minister’s discretion. David Cameron and Ed Miliband should thus be pressed hard to commit to such change. If no such change is forthcoming it would create major problems, but other more radical options do exist. In February 2013 the Lords debated a motion (again proposed by Lord Steel) to refuse introduction to any new members until reform was agreed to get the size of the chamber down. At the time, the motion was dropped. If the party leaders do not take the necessary action, next time peers may choose to stand their ground.

Our report has been welcomed by various senior figures. Its launch in the Lords was chaired by the former Lord Speaker, Baroness Hayman. Lord Jay of Ewelme, chair of the House of Lords Appointments Commission until 2013, provided a preface, and argued at the launch that ‘we have to get the numbers down… so we do need a combination of discipline on appointments and encouragement to retire’. He lent his support to ‘giving the Appointments Commission more powers to implement a new agreement’, including a size cap and appointments formula for party peers.

Likewise, Lord Grocott, former Lords Chief Whip 2002-08, argued for ‘the Appointments Commission deciding on the frequency of new batches of appointments and deciding on the overall numbers’ because the size of the House of Lords is now ‘verging on the ridiculous and it needs to be dealt with’. The report also has the formal backing of the Hansard Society and the Constitution Society, while Peter Riddell of the Institute for Government has said that it ‘makes a powerful, convincing and evidence backed case for urgent action by the Prime Minister to adopt a new approach to appointing peers’.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on the Constitution Unit blog and is reposted with permission. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Meg Russell is Professor of British and Comparative Politics, and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit, at UCL. She is author of The Contemporary House of Lords: Westminster Bicameralism Revived (Oxford University Press, 2013) and numerous other publications about the Lords. Enough is Enough: Regulating Prime Ministerial Appointments to the Lords was published on 9 February 2015 by the Constitution Unit.

Meg Russell is Professor of British and Comparative Politics, and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit, at UCL. She is author of The Contemporary House of Lords: Westminster Bicameralism Revived (Oxford University Press, 2013) and numerous other publications about the Lords. Enough is Enough: Regulating Prime Ministerial Appointments to the Lords was published on 9 February 2015 by the Constitution Unit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

“@ConUnit_UCL: Enough is enough: Time to regulate PM appointments to the Lords. https://t.co/nM60p7tvt9” worth a look for #ukpol

Enough is enough: Time to regulate PM appointments to the Lords. Meg Russell sets out the key points of the report. https://t.co/KGLu7XOGmM

Enough is enough: Time to regulate prime ministerial appointments to the Lords https://t.co/FnX2dEaK0o