The Conservatives’ BME MPs may be game changers in the way we think about ethnic minority representation

It has long been assumed that the ethnicity of voters will translate into ethnicity of candidates; and that ethnicity of MPs will in turn improve the representation of BME interests in Westminster. But is this the case? Maria Sobolewska argues that the recent increase in BME candidates for the Conservative Party may be a ‘game changer’ in how we view these relationships and trends.

Diane Abbott: A trailblazing black MP (Credit: Policy Exchange, CC BY 2.0)

A recent report from the British Future, which indicates that the Conservatives may have more BME MPs in the next parliament than Labour, is one of many recent contributions about representation of ethnic minorities in Westminster. It differs however in its thrust: it does not link the issue of presence of minority MPs with minority voters. Following the 2010 general election I made an observation that the severing of this link has been a major distinguishing feature of that election: out of the 27 BME MPs who were returned at this election, only seven represented seats that had more than 40% minority residents, and ten represented seats in which minorities amounted to less than 10% of the population.

This significant change in the profile of minority MPs and candidates is set to continue at the next election, with the Conservative safest prospects also predominantly representing ‘white’ seats, and many Labour BME hopefuls as well. Perhaps it is time to ask what it may mean for our understanding of representation. I argue representation of minority interest is weakly related to ethnicity of MPs and that the target audience for the show of party diversity is not ethnic minority voters.

Assumptions about the link between ethnicity of voters and MPs.

The first question to ask is to what extent our thinking about representation no longer describes reality. Two other reports published recently attempt to translate the number of BME voters into the numbers of BME MPs directly. The Insight Public Affairs analysis compares the proportion of the parties’ voters who are of minority origin and the proportion of their MPs who are. Another study, for Demos, argues that any shortfall of minority MPs to minority voters constitutes a ‘penalty’, implying that all minority votes should deliver a minority representative, and if they do not, voters are somehow penalised.

This makes a strong assumption that ethnicity of voters and MPs should be related, which can be problematic. First and foremost the assumption that minority voters should be matched with minority MPs, can imply the mirror-assumption, that ethnic minority MPs are only an option for diverse seats. Such ‘ghettoisation’ of ethnic MPs has been identified as one of the reasons for general under-representation of minorities, as these seats may be limited in number. Additionally, since these diverse constituencies tend to be urban and deprived areas, the Labour party becomes the only option for the ethnic minorities, making it hard for Labour to resist taking their votes for granted. Finally, it raises an interesting question about the role of those minority MPs, from both main parties, who were elected by white people.

Does it matter what ethnicity an MP is and who voted for them?

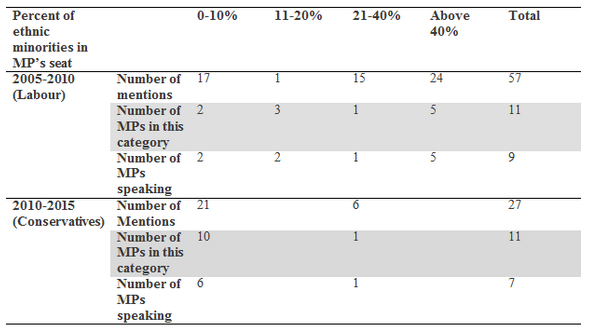

Does the ethnicity of the MP and their constituents matter in how well they can or will represent ethnic minorities in Parliament? A paper based on the analysis of Hansard records of parliamentary activities of MPs – both white and minority origin- between 2005-2010 shows that white MPs who have significant proportion of ethnic minority constituents are responsive to their interests and defend them in Parliament. A crude look at the more recent cohort of Conservative minority MPs between 2010-2015 shows that the opposite is true for Conservatives: many of them do not mention ethnicity in Parliament at all- and the relationship with the demographic makeup of their constituency seems crucial. Table 1 shows simply the direct mentions of ‘ethnic minority’ in both speech and written parliamentary activity (the irrelevant entries are excluded) in the two last Parliaments.

In order to compare like with like, I compare Conservative MPs in this Parliament with Labour MPs in the last, since both parties are therefore in a party of government (this usually limits the numbers of freely raised points). I also exclude, as outliers, two most prolific Labour MPs: Diane Abbot and Keith Vaz, making this test a very conservative one: ie giving the new minority Tory MPs the best chance to mention ethnicity. Yet, the number of mentions halves, as Labour minority MPs mentioned ‘ethnic minorities’ 57 times, and the Tory minority MPs only 27 times.

Ethnic makeup of their seats seems to explain it for the Conservatives: those who represent seats with fewer than 10% constituents barely mention ethnicity at all: six of these MPs are responsible for 21 mentions, three per person. However, this is not the case for Labour: two Labour MPs in this category made 17 interventions. This suggests that the importance of party affiliation is not trumped by ethnicity. This is well known by voters: 70 percent of BME respondents said in 2010 that Labour looks after the interests of Blacks and Asians fairly or very well.

Table 1: Mentions of ‘ethnic minorities’ in the House of Commons by ethnic minority MPs and by the ethnic diversity of their seats in the last two parliamentary sessions

Who is the target audience?

With the Conservative MPs not voted for by ethnic minorities, and not really representing them in Parliament (although let’s remember that the test was rather crude), the question is who do they represent? Or, perhaps more to the point, who benefits from their presence in Parliament, and who lobbies for increasing their presence?

The Conservative party has two incentives to increase their diversity. Firstly, without the support of ethnic minorities, it will be increasingly hard for the party to win an electoral majority. A cautionary tale from the US- an election seemingly decided against the Republican party on ‘demographics’- is something on the party’s mind. Yet, I also argued that the need to detoxify their brand is not limited to minorities. As the younger more tolerant generations are replacing the more traditional electorate, many white voters may care that their party of choice is not ‘nasty’ about race. Young, cosmopolitan and well educated electorate may well be the audience for the show of diversity more than ethnic minorities are. Following this line of thinking, one would expect the right wing parties, who may be weighed down with accusations of racism and a ‘nasty’ past, that would care more about selecting- and electing more minority candidates.

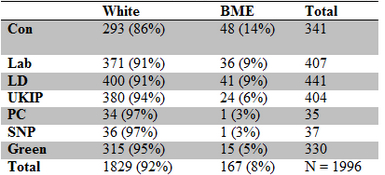

The new Representative Audit of Britain study collected information on candidate ethnicity for all major and smaller parties, and confirms this instinct. Even though the numbers are only indicative, table 2 shows that out of the three main parties, the Conservative party has the highest proportion of ethnic minorities (14 percent to Labour’s and Lib Dems’ nine percent); and similarly out of all the smaller parties, UKIP stands the largest proportion of minority candidates (six percent to Green’s five, SNP’s and Plaid Cymru’s three.

Table 2: Candidate ethnicity (by party – new candidates only)

It may be time to go beyond our simple assumption that ethnicity of voters will translate into ethnicity of candidates; and that ethnicity of MPs will translate into representation of BME interests in Westminster. There is nothing simple about these relationships anymore and we need a new way of thinking about representation to match the new political reality.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Maria Sobolewska is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester. She and her colleagues conducted the Ethnic Minority British Election Study at the 2010 General Election. She is a team member on the Representative Audit of Britain survey of Parliamentary Candidates at the 2015 General Election and on the international project studying representation of citizens of immigrant background. Her book The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain, co-authored with Anthony Heath, Stephen Fisher, Gemma Rosenblatt and David Sanders has been published with Oxford University Press. Many of her papers are available without paywall here.

Maria Sobolewska is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester. She and her colleagues conducted the Ethnic Minority British Election Study at the 2010 General Election. She is a team member on the Representative Audit of Britain survey of Parliamentary Candidates at the 2015 General Election and on the international project studying representation of citizens of immigrant background. Her book The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain, co-authored with Anthony Heath, Stephen Fisher, Gemma Rosenblatt and David Sanders has been published with Oxford University Press. Many of her papers are available without paywall here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] to raise more questions about ethnicity and racism than other MPs, ethnicity does not seem to trump party affiliation on these matters for the new cohort of Conservative ethnic minority MPs in the […]

Politics lecturer Maria Sobolewska questions the relationship between the ethnicity of voters and their MPs.

https://t.co/3WzNptYFF9

Rethinking race & representation: good post @smthgsmthg on the changing nature of ethnic diversity in politics https://t.co/FHlJXixrmU

#Democratic #UK #tcot

The #Conservatives’ BME MPs may be game changers in the way we think about ethnic minority . https://t.co/OEnEVhA3gy

The Conservatives’ BME MPs may be game changers in the way we think about ethnic minority representation https://t.co/ZvvwbcGiLl

The Conservatives’ BME MPs may be game changers in the way we think about ethnic minority representation https://t.co/6TLXx5m47j

The Conservatives’ BME MPs may be game changers in the way we think about ethnic minority representation https://t.co/yyjWcCjQIa