Under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to be able to govern

During the election campaign, much attention has been focussed on the prospect of some kind of accommodation, or deal between the Labour and Scottish National Parties. However the discourse on the nature of such an arrangement rests on outdated notions which do not take into account the Fixed Term Parliament Act (FTPA) which changes the dynamic quite dramatically, according to Colin Talbot.

Carpeted out? (Credit: Helmand PRT Lashkar Gah, CC BY NC SA 2.0)

The media is rife with speculation about who will do deals with whom after May 7thand what the possibilities are. What is obvious is that most of them are working on old assumptions about how Governments are formed which predate the Fixed Term Parliament Act 2011 (FTPA), which has fundamentally changed the way these things work.

What does the law say?

For example, there’s been big speculation about what happens if a minority Labour or Conservative government gets defeated on their Queen’s Speech. Which rather misses the point – nothing happens. The Government doesn’t fall. There is no dissolution of Parliament.

Under the FTPA the only circumstances in which a Government falls would be if (a) they resigned – unlikely but not impossible or (b) the following is passed by a majority in the House of Commons

“That this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government”.

Nothing else forces a Government out of office – not defeat on a Queens Speech, a Budget, a key piece of legislation, a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister, nothing.

Of course there may be political circumstances where a Government chooses to take such a defeat seriously and resigns. Or, more likely, they could put down the above motion themselves and dare their opponents to kick them out.

Even if the above motion is passed and the current Government is ousted there is then a 14 day period in which attempts to form a new Government can take place. And, as we often see on the Continent, that can often be an attempt by the current Government to cobble together a new combination to win a vote of confidence.

Which brings us to the second part of this process, accepting a new Government. Here the FTPA says that this must take the form of a majority of the House of Commons passing the following resolution:

“That this House has confidence in Her Majesty’s Government.”

Note the important difference that this is a positive affirmation of confidence – arguably it would be harder to pass this motion than the no confidence one, simply because it would politically endorse the Government on offer, which might be awkward for some.

What might happen in practice?

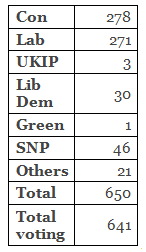

Let’s try a thought experiment based on the latest projection (26 April) from YouGov on who might get what MPs on May 7th:

Note: “others” includes the 4 members of the Speakers team, who don’t vote, and currently 5 Sinn Féin MPs who don’t take their seats.

Let’s assume on these figures David Cameron seeks to stay on as Prime Minister and form a minority Government. Forget the Queen’s Speech and any other vote in Parliament, the only vote that could get Cameron out of No. 10 is if the House of Commons passed by a majority the proposition “That this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government” – in other words 321.

Labour, the SNP, and the Greens could all be expected to vote for such a motion – 318 votes. With (currently) the 3 Plaid Cymru the ‘anti-Tory vote already reaches the magic 321 – so Mr Cameron would be out.

At this point both Mr Cameron and Mr Miliband could embark on negotiations to try and get votes to form a Government – in practice it would probably only be Labour doing this and David Cameron would probably have announced his intention to step down as Tory leader.

Labour would need to assemble the magic 321 or more votes for a motion “That this House has confidence in Her Majesty’s Government.” That might be tricky. If Labour sticks to its “no deals with the SNP” position it would be hard to assemble the 321 votes unless the SNP were forced to vote for the new Government.

This could happen because they are pledged to “lock out” the Tories and are unlikely to want to force a new General Election, which is what would happen if Labour failed to win the vote. So it could come down to a ‘game of chicken’ as to who blinks first – Labour or the SNP.

Let’s assume the opposite of the above scenario happens – David Cameron accepts he’s effectively ‘lost’ the election, even although he’s got more seats, goes to the Queen and resigns and recommends Ed Miliband be asked to form a Government.

Getting and holding onto Government is much easier for Labour in these circumstances. It is very unlikely the Tories would put down a ‘no confidence’ motion immediately, having just conceded power. And no of the smaller parties are very likely to either. Even if say UKIP were to do so, the Tories would almost certainly abstain and Miliband would remain as Prime Minister.

The power of the executive and minority government

In the past minority Governments have managed to hang on in Government for quite long periods. The FTPA makes this even easier and much clearer what would, and would not, force a Government out.

One of the favorite phrases of journalists at the moment is “confidence and supply”. The FTPA makes this term more or less redundant. The ‘supply’ bit was always a bit of a myth, as I have pointed out before. It is very hard to alter Government tax and spend policies and in any case any defeat or amendment would not be an issue of ‘confidence’ issue – it never was and FTPA rules it out completely. The ‘confidence’ bit has also changed as a result of FTPA, as discussed above. In reality any minority Government doesn’t need a so-called ‘confidence and supply’ arrangement to be able to govern.

Our system is generally heavily weighted in favour of the executive, HM Government, against the legislature, Parliament, and although the power of ‘Crown prerogative’ has been slightly modified in recent years it is still very strong.

This means a lot of the talk about how the SNP could ‘blackmail’ a minority Labour Government, or UKIP a Tory one, is vastly exaggerated.

Of course a minority Government would have to negotiate around specific bits of legislation it wanted to pass, but even that may prove a lot easier than many expect. Getting its tax and spend policies through is even easier – and no-one can propose to ‘end austerity’ (as the SNP supposedly does) because Parliamentary rules don’t allow it.

There’s a wider point here too – the British Political Tradition is always said to have favored ‘strong government’ but current voting patterns suggest people are much less concerned about that idea. Maybe the British electorate would welcome a Government that had to constantly negotiate policies rather than act like an “elective dictatorship”? We are probably going to find out.

—

Note: this post originally appeared on Colin’s personal blog and is reposted with permission. It represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit, the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—-

Colin Talbot is Professor of Government at the University of Manchester

Colin Talbot is Professor of Government at the University of Manchester

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

A very interesting and important piece Colin. Thank you. I should say I have no expertise in the British case, but, as a scholar of parliamentarism, I’m not convinced that a Prime Minister could continue in office if she/he lost an amendment on the Queen’s Speech – politically but also constitutionally. Yes, the 2011 Act specifies what is a confidence vote and fails to mention the Queen’s Speech as a confidence vote. Hence your perspective.

But perhaps the Queen’s Speech could/should be viewed as part of the government formation process (the very last stage, per the Cabinet Manual) and not as a standard confidence procedure? Thus, while the 2011 act deals with the ‘breaking of governments,’ the role of the Queen’s Speech remains intact as it is part of the ‘making of governments.’ Many parliaments have an ex-post vote to confirm in office the already appointed government and/or confirm their policy programme.

Very interesting times and perhaps a good reason to revisit the framework for government formation in the UK.

A forthcoming vol on parliaments and government formation (https://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780198747017.do) may be of interest (apologies for the self-promotion).

@Briandamge64

https://t.co/wI1gstNvgb

@jimmychip

Article re reality of minority government: https://t.co/XRnYbsVC9N – The last paragraph is on the nail, for me.

[…] Fixed Term Parliaments Act for what kind of Government may emerge from the General Election. In a previous blog, Colin Talbot argued that a minority government could govern relatively comfortably given the Act, […]

Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to govern https://t.co/G6IDvuGPcp

Aa minority Government doesn’t necessarily need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to be able to govern https://t.co/JUbdpMhPV6

A minority Government doesn’t necessarily need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to be able to govern https://t.co/LsQu8ZStIY

RT @lizwithhat: Under Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Govt doesn’t need “confidence and supply” to govern: Colin Talbot https://t.co/…

Under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement … https://t.co/Amcn3kEUTp

RT @andrewducker: Under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to… http:/…

The impact of fixed term parliaments https://t.co/ZYOz96VOyr

Under Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need “confidence and supply” to be able to govern https://t.co/AbActYfrMz

Under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to … https://t.co/XhE0XMtxCc

@AndrewColeman1 Read this blog. Remember, Tories will still be the government after 7 May. https://t.co/NBrBSmlO5w

“Forget the Queen’s Speech and any other vote in Parliament, the only vote that could get Cameron out of No. 10 is if the House of Commons passed by a majority the proposition “That this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government””

A Government that lost the Queen’s Speech – if it did not resign automatically – would invite a vote of no confidence and would lose it.

“Of course a minority Government would have to negotiate around specific bits of legislation it wanted to pass, but even that may prove a lot easier than many expect. Getting its tax and spend policies through is even easier – and no-one can propose to ‘end austerity’ (as the SNP supposedly does) because Parliamentary rules don’t allow it.”

The SNP can vote against any austerity budget in toto. The very fact that it need not lead to an election makes this easier to do. (eg the SNP could vote down the budget but support Labour in a vote of confidence – or not) The government could, arguably, ‘carry on’, but it wouldn’t really be ‘governing’ anymore unless it renegotiated a new budget which would pass the House.

The entire idea that the SNP would have no choice but to prop up a Labour gov under ANY and ALL circumstances (an obvious absurdity when given 2 seconds thought), is misconstrued, and ignores the fact that Labour lost in Scotland. It also underestimates how sophisticated the Scottish electorate have become in the last 2 years

“Under the FTPA the only circumstances in which a Government falls would be if (a) they resigned – unlikely but not impossible or (b) the following is passed by a majority in the House of Commons…”

That isn’t right. The Act does not say that.

A Government *only* comes to an end when the Prime Minister resigns (or dies). Once upon a time the sovereign could remove the PM, but those days are long gone.

So, Gordon Brown’s government ran from 27 June 2007 i(when the Queen appointed him) until 11 May 2010 (when he resigned four days after the election for a new Parliament). Margaret Thatcher’s government ran from 4 May 1979 – 28 November 1990. Every single government ends with the resignation of the Prime Minister, and may be uninterrupted be general elections for Parliament.

The issue then is when must a Prime Minister resign? The answer (and this is Convention only) is when he or she no longer commands a majority of the House of Commons.

How can a Prime Minister who once has this, lose it?

One way is that the composition of the Commons may change in a General Election, but that is not the only way.

it may be that a succession of byelections change the composition of the Commons. it is also possible that he loses this because a group of MPs change allegiance whether from his own party (eg the Liberals under Gladstone because of Home Rule) or another (eg if the SNP swapped sides after the 2015 GE.)

Once the PM has lost the support of the Commons, and there is another person who has it (usually the leader of the opposition but not necessarily – see the change of government during WWII) the PM *must* resign, recommending to the sovereign that she calls on that other person to form a government.

Now in some circumstances it may be unclear whether a PM still commands the confidence of the House of Commons. that is tested by a vote of confidence, often tabled by the opposition.

How has the Fixed Terms Parliaments Act changed any of this? Only in one respect: it has made the PM’s position weaker, not stronger as you suppose.

Prior to the FTPA the PM could ask for a dissolution instead of simply resigning. The Convention had become that this was always granted by the sovereign. This acted as a deterrence (the opposition may not want an election) and a fresh chance (a new Commons may be differently constituted and support the PM). The Act takes this power away from the PM. His only option now is resignation.

The FTPA alters when Parliaments come to an end (through dissolution) not when governments come to an end (through resignation).

Eye-opening article in @democraticaudit by @colinrtalbot about how & why #FTPA adds stability to minority government. https://t.co/iZL1x2aIBE

Under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, a minority Government doesn’t need a “confidence and supply” arrangement to… https://t.co/rMIiOWcTPY