David Cameron may have to emphasise the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to his MPs if he is to get through this Parliament

David Cameron won a General Election majority against seemingly insurmountable odds in May 2015. But given the recent history of the Conservative Party, it looks possible that divisions over Europe and other issues could make the road to 2020 a bumpy one. Christopher D. Raymond argues that given the nature of the issues at stake and the Conservative majority, the Prime Minister’s best bet may be to emphasise party label and the partisan consequences of voting against the whip if he is to get through the next five years unscathed.

Credit: Esa Pitkanen, CC BY NC SA 2.0

Many observers expect the Prime Minister will face difficulties maintaining his slim parliamentary majority on a number of key issues during this parliamentary term. This will be the case particularly on issues relating to the UK’s future relationship with the European Union, which have long divided the Conservative Party internally. Such continued internal division has already been made evident during this term by the recent backbench dissent regarding the neutrality of Whitehall during the upcoming referendum. To maintain cohesion on these issues, the government whips will have their hands full.

In a legislative setting generally accustomed to strong party discipline, these developments compel observers of parliamentary affairs to revisit the debate regarding two types of ‘party’ effects on MPs’ voting behaviour. On one hand, party unity in Britain has always been enforced by strong whip systems that have been among the most effective in maintaining strict party discipline. On the other hand, the increasingly rebellious behaviour of MPs reminds us individual MPs have preferences that do not always line up well with the party line. In other words, the whip is but a tool to maintain discipline, as a great deal of party unity is explained by the fact that parties are (usually) a collection of like-minded people with similar interests and goals.

New research, however, suggests there may be a third dimension to the role of party in shaping MPs’ voting behaviour: the party identification of MPs. This argument builds on the notion of party identification developed in the study of voting behaviour among the general public. According to this view, many voters develop psychological attachments to parties that lead them to identify with the party in such a way that they see the party as an extension of themselves. As a result of party identification, party identifiers tend to vote for the same party in election after election – even if voters’ policy preferences do not align with the positions of the parties.

There is reason to believe MPs exhibit similar tendencies in their voting behaviour on divisions in Parliament that cannot be explained by the disciplinary or shared-preferences interpretations of party unity – as recent research looking at the House of Lords suggests. In a forthcoming article, my co-author Marvin Overby and I sought to test this party-as-identification argument. Specifically, we examined the bill legalising stem cell research in the UK (the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Research Purposes) Regulations bill decided in the House of Commons in December 2000). Because this bill was decided as a free vote – in which MPs are not whipped by their party leaders – this allows us to rule out the effects of party discipline. By making use of a survey of MPs – the British Representation Study 1997, which included several measures of MPs’ personal preferences relevant to stem cell research – we were also able to control for the other major explanation of ‘party’ effects on voting behaviour. Thus, we argue, any lingering effect of MPs’ party affiliation could be attributed to the party identification of MPs.

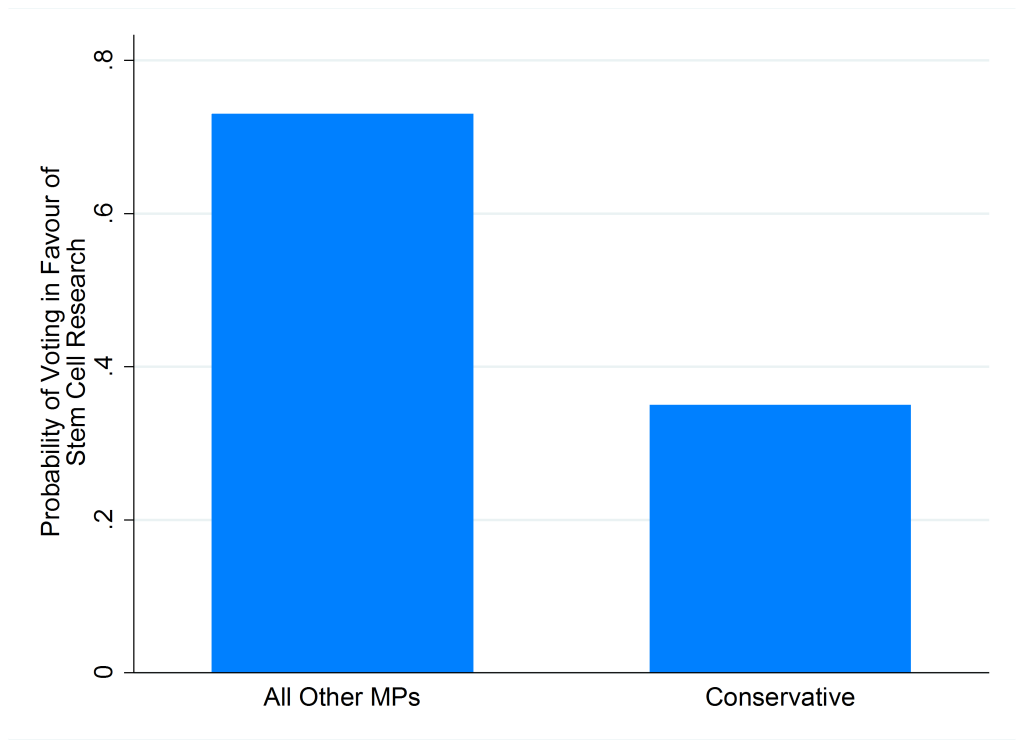

What we found was that even after controlling for MPs’ preferences, ‘party’ continued to play a role in shaping MPs’ voting behaviour on the bill. All things being equal, the probability that MPs would vote in favour of legalising stem cell research was 0.73; for Conservative MPs, however, the probability of voting in favour was estimated at only 0.35 (see Figure 1). Because this difference in predicted probabilities excludes any impact of party discipline, and because we control for MPs’ preferences, we conclude that Conservative party identification made Tory MPs significantly less likely to vote in favour of legalising stem cell research. Although our conclusions are derived on the basis of only one free vote, these findings suggest we at least need to consider the role party identification plays in shaping the voting behaviour of MPs in order to understand party unity in Parliament (as well as rebellions against party leaders).

Figure 1: The estimated difference in the probability of voting in favour of legalising stem cell research between Conservative and other MPs (Net of MPs’ Preferences)

These caveats aside, this party identification argument may be instrumental to understanding the European question unfolding in the House of Commons. Consider the recent rebellion regarding the upcoming EU referendum: despite the fact that 50 MPs have already signed up for Steve Baker’s Conservatives for Britain (with another 50 said to be ready to join), only 27 MPs rebelled against the government’s plans. Although the whips may have persuaded some Eurosceptic MPs not to defect, the Government’s efforts to maintain cohesion in this instance seemed more like pleading instead of whipping hesitant MPs, and the fact that the government offered last-minute concessions to win over would-be rebels suggests it feared its backbenches more than they feared the whip. Moreover, the fact this bill saw fewer defections than expected suggests many of these Conservative MPs voted against their own preferences by siding with the government due to the fact that they identify with the party.

More broadly, the slim Tory majority suggests the whip will not be an effective tool on similar issues during this term, as backbenchers know the government cannot afford to alienate them without permanently jeopardising its slim majority (or seeing additional MPs defect to UKIP). Instead, our research would suggest that the Prime Minister may have to rely on the party identification of MPs in order to maintain cohesion, emphasising the partisan consequences of a divided Conservative Party. Similarly, other parties whose members are generally more pro-European may have to rely on party identification in order to maintain cohesion, as in the case of Labour’s Eurosceptic wing.

—

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Christopher D. Raymond is Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

David Cameron may have to emphasise the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to his MPs https://t.co/dUyFmPARy5

David Cameron must stress the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to get his MPs through this Parliament https://t.co/XAEkGLQV1k

Cameron may have to emphasise partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to MPs if he is to get through this Parl https://t.co/HExJOg3fO5

David Cameron may have to emphasise the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to his MPs if he is to get t… https://t.co/uTYZSh2Vem

David Cameron may have to emphasise the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to his MPs if he is to g… https://t.co/S0uzCay4ti

David Cameron may have to emphasise the partisan consequences of a divided Tory party to his… https://t.co/z5Sk2YfAft https://t.co/Oh3jYtqJof