Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem

Roger Liddle explains why removing the UK’s commitment to “ever-closer union” is so important to the PM as he renegotiates the UK-EU relationship. But if he does succeed in getting rid of it, how much would really change?

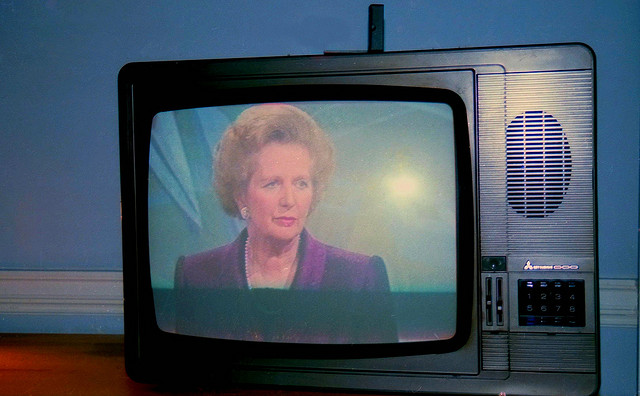

Credit: R Barraez D’Lucca, CC BY 2.0

David Cameron sets great store by his insistence that the treaty language on ‘ever-closer’ union should no longer apply to the UK. Pro-Europeans tend to scoff at this, but for him it is deeply significant, because it is vital in convincing Conservative sceptics that it is worth Britain remaining in the EU.

The prime minister is targeting his renegotiation strategy at those Eurosceptics whose constant refrain is that the British people voted to join a common market in 1975, but never to join a political entity which is now the European Union.

Cameron and George Osborne want to claim that they are taking Britain’s EU membership back to the original motivation. For them, establishing clear blue water between Britain and the continental concept of ‘ever-closer’ union has vital political symbolism. The PM made this clear in his June 2015 European council statement to the Commons.

The chancellor has talked in similar terms about making our membership of the EU all about “a single market of free trade” again.

Of course, this line of argument is tendentious and historically inaccurate. In the 1960s and 70s, it was the anti-Europeans who opposed British membership of the ‘common market’, to which they attached all kinds of adverse connotations for British farmers: higher food prices, denial of access to cheap New Zealand lamb and butter, and on the left, free market rules that would inhibit the potential for socialist planning. In the same era, it was the pro-Europeans who advocated support for the ‘European Community’ as a new coming together of Europe which it was in the British national interest to join.

On the Labour side of the debate, pro-Europeans such as George Brown and Roy Jenkins accepted that the economic arguments for membership were finely balanced, but the political arguments decisive. On the Conservative side, both Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher made a powerful case for British membership on political grounds.

During the 1975 referendum campaign, the government issued a pamphlet to every voter. It set out the aims of the common market:

- “To bring together the peoples of Europe”

- “To raise living standards and improve working conditions”

- “To promote growth and boost world trade”

- “To help the poorer regions of Europe and the rest of the world”

- “To help maintain peace and freedom”

These are ambitious and progressive political objectives for an entity whose only rationale was allegedly the promotion of free trade! Yet anti-Europeans have propagated the myth that ‘we only ever voted to join a common market’, with considerable success.

Edward Heath fully accepted the phrase ‘ever-closer union’ in the UK treaty of accession, as it had been contained in the 1957 Treaty of Rome to which the UK committed. Harold Wilson did not seek to change it in his 1974-75 ‘renegotiation’.

In any event, the present treaty text is a modification of the original Rome version. It now calls for an “an ‘ever-closer’ -union” of “the peoples”, not, pointedly, the member states, and goes on to say that this union should grow closer in a Europe which acts only on the principle of subsidiarity. John Major secured thisamended version at the Maastricht summit in 1991.

However, the sentiment of ‘ever-closer’ union grates with Eurosceptics in Britain as a lingering symbol of a ‘United States of Europe’ ambition. Tony Blair felt this. He actually succeeded in removing ‘ever-closer’ union from the original draft of the failed constitutional treaty in 2003, but it later reappeared, essentially because Blair had more important British objectives to secure in those negotiations.

At the June 2014 European council, Cameron succeeded in securing agreement to a political interpretation of what ‘ever-closer’ union means today:

The European council noted that the concept of ever-closer union allows for different paths of integration for different countries, allowing those that want to deepen integration to move ahead, while respecting the wish of those who do not want to deepen any further.

Cameron now wants to go further and secure a formal British opt-out from ‘ever-closer’ union. He is not insisting on a treaty change that would apply to all member states, but wants to cut a special deal for Britain.

If this demand were viewed simply on its own merits, it would undoubtedly encounter resistance. Why should the UK now secure an opt-out from a founding principle of a treaty that it signed 43 years ago? If Britons have lived with the supposed mandate for ‘ever-closer’ union for over four decades, what is the problem? The EU still seems some considerable distance from the realisation of a ‘United States of Europe’.

There is also much at stake for our partners. Why agree to a high-profile symbolic retreat from the general commitment to European integration by a single member state, when the EU itself faces powerful forces for disintegration from within? Who would be the next to follow?

Cameron may well try to link his demand for an opt-out from ‘ever-closer’ union to his acceptance of the need for closer integration by other member states, particularly those in the eurozone. But this raises further questions. Would the abandonment of ‘ever-closer’ union apply to all states outside the eurozone? Some ‘euro-outs’, possibly in eastern Europe (Hungary, for example), might quite like that, but not all.

Then there is the question of the practical effect of any UK opt-out. What would change as a result? Does the removal of a British commitment to ‘ever-closer’ union rule out closer British cooperation in future in other non-euro fields such as defence and external relations, energy and climate change, migration and asylum? Would it be seen as giving the British a right to opt-out of any future piece of legislation to which they objected? Why should the British have the right to be members of a ‘pick and choose’ Europe, when the basic principle of European integration is that the same set of rules should apply to all – even though the existence of much ‘variable geometry’ means that this principle is sometimes honoured only in its breach.

The council and commission lawyers will almost certainly find a way through this minefield. What might be possible would be a commitment from our partners to include the June 2014 European council statement in a legally binding protocol that in due course would become part of the treaties. Our partners might accept an addendum that the UK does not see its commitment to membership of the EU (and all its treaty obligations) as extending to the goal of ‘ever-closer’ union.

But the price of such an agreement will probably be new language that would clarify that a British opt-out from ‘ever-closer union’ could not be used more widely by Britain to opt out of its existing and future EU legal obligations.

In other words, Cameron could claim victory in securing the removal of a piece of unwanted symbolism, but nothing of any substance would change.

—

This post originally appeared on the LSE BrexitVote blog. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Roger Liddle is co-chair of Policy Network and a member of the Lords. This article is an adapted extract from his forthcoming book The Risk of Brexit: The Politics of a Referendum. It does not represent the position of the BrexitVote blog, nor the views of the London School of Economics.

Roger Liddle is co-chair of Policy Network and a member of the Lords. This article is an adapted extract from his forthcoming book The Risk of Brexit: The Politics of a Referendum. It does not represent the position of the BrexitVote blog, nor the views of the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem, by Roger Liddle https://t.co/HeQpBy4CUe #Brexit #EU

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem https://t.co/mv5Hc84nXo

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem https://t.co/75sNBT0nVL

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem https://t.co/NxNOAgdtW2

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem https://t.co/pxxCBFDBin

.@liddlro in @democraticaudit argues removal of ever closer union wd mean Cameron victory but no change of substance https://t.co/cKeXgvMG5H

Understanding Cameron’s renegotiations: the ‘ever-closer union’ problem https://t.co/XEMfTCGR9L https://t.co/bf9GJHmjjP