Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns

Immigration is a huge element of contemporary political debate, and it continues to divide and polarise opinion, while fuelling the rise of UKIP and other radical parties across Europe. Here, Craig Johnson and Sunil Rodger argue that while hostility to immigration may be in part to do with economics, a sunny economic outlook is unlikely to reassure immigration-sceptics of its worth.

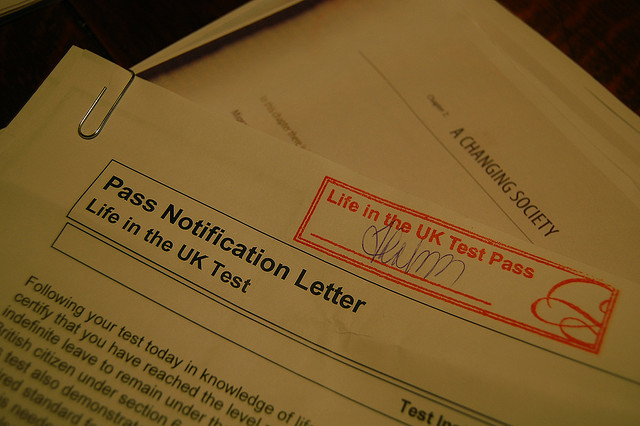

Credit: Jayneandd, CC BY 2.0

Immigration continues to be a dominant feature of political debate in Britain. For the most part, attitudes are negative. In part, this reflects the idea of immigration as a threat. It also generates a feeling of blame, as time and again political parties promise to reduce it yet subsequently fail to do so.

Following the 2015 general election, David Cameron has insisted that his government remains committed to bringing down immigration from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands per year, blaming the failure to do so in the last parliament on the Liberal Democrats. Most of Cameron’s interventions on immigration revolve around the economy, and so far much of his EU renegotiation package has focused on ‘benefit tourism’. The Conservative 2015 general election manifesto promised a tough stance highlighted in economic terms: “We will insist that EU migrants who want to claim tax credits and child benefit must live here and contribute to our country for a minimum of four years”.

Similarly, prior to the 2015 general election Labour also emphasised the relationship between immigration and the economy. Their manifesto promised that immigrants ‘won’t be able to claim benefits for at least two years’, and that they would maintain the cap on non-EU immigrants coming to Britain to work.

However, underlying the argument put forward by both Labour and the Conservatives is that it is primarily economic concerns that drive anti-immigration attitudes, rather than cultural ones. This is understandable. Economic concerns can often be addressed through facts and figures, whilst cultural concerns veer into dangerous territory and risk accusing voters of prejudice. The latter is fraught with political difficulties, as Gordon Brown discovered following his meeting with Gillian Duffy. By sticking to economic concerns, politicians are on what they believe to be safe ground. And it follows the mantra of ‘it’s the economy, stupid’: make the economic arguments, win them, and voters will reward you.

However, our research casts doubt upon these arguments. We find that economic concerns have very little effect on voters’ attitudes to immigration in Britain. Whether voters are thinking about their personal economic situation or that of the country as a whole, their perceptions of the economy are only weakly related to hostility to immigration. Much more important are concerns relating to identity, class and culture.

This creates a big problem for political parties. In their negative language about immigration, they reaffirm it as something to be fearful of and angry about. In doing so, they set themselves a greater challenge to solve – particularly when their approach to doing so, using economic framing, does not address voters’ underlying concerns around culture and identity.

This paradox has been described as one between beer drinkers and wine drinkers. The beer drinkers listen to voters’ concerns, while the wine drinkers proclaim the benefits of immigration in an increasingly liberal world. The wine drinkers have a point: studies mostly highlight the economic benefits that immigration provides. However, this is irrelevant if voters are ignored and angered in the process. The cultural arguments for immigration cannot be left out of the mainstream of political debate.

Addressing the cultural and identity aspects of immigration is a very difficult task. Engaging with those who have concerns about immigration risks alienating those who defend its benefits. It is a difficult but ‘inconvenient truth’ that both sides might have a point. A defence of immigration must accept the concerns put forward by voters about language, identity and community. Increased support for UKIP in recent years reflects those concerns. Only by addressing these can pro-immigration parties begin to tackle the hostility to immigration that exists.

—

Note: this piece represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Craig Johnson is a PhD student in Politics at Newcastle University.

Sunil Rodger is a PhD student in Digital Civics at Newcastle University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Economic concerns have little effect on voters’ attitudes to immigration | Cultural arguments cannot be ignored https://t.co/OA2TNtizDi

@cjnu1 “Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns” https://t.co/IQnHf2LiTu

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns, write @sunildvr & @cjnu1 https://t.co/Uk7A03iCpF

The problem with the ‘wine drinkers’ arguments’, and indeed those of the elite in general (‘immigration is a marvellous thing’), is that they seem clearly false to those who are on the sharp end. The elite does not have to bear the brunt of ever fuller doctors’ surgeries, tatty overcrowded schools and creaking systems in all other areas. The classic elite ‘trickle down’ argument simply does not appear to apply as they get better off while the people appear to be going in reverse.

The other serious problem with this argument is that elite across the EU want unlimited immigration, but when they are panicked they try (specially in the UK) to imply to their voters that they believe the opposite, using vote catching mood words to give the impression that they are serious about ‘doing something’. The classic examples come from both Tory and Labour politicians, and in typical political irony, on occasions they use phrases that UKIP would find too extreme

A further point which arises out of this general mood of anti-immigration fostered initially by the main parties and not indeed by UKIP – and it is that the words are never translated into actions, because they cannot be (EU rules). Were the main parties to come clean and confess they want unlimited movement of people (and would appear to want to therefore scrap arrangements like the NHS free at point of delivery which have to be available to all within the EU who demand them), they might have had a small chance of neutralising this issue. But of course it is the EU and its agencies which effectively control many aspects of immigration, and UK governments have very little power over it – so the present Prime Minister has been seen to be shallow, incapable and devious in his use of words about the matter. And as you must realise, the 2015 Manifesto Pledge about benefits (how long ago that was…) will of course not be carried forward without EU agreement. Which it will not get. These are like so many other of the pledges on this subject, dragged out of a reluctant government through gritted teeth against a background of voter anger, all the while knowing that they cannot be implemented and trying to smear others as ‘racist’ for highlighting the subject.

If you think you have been lied to on an issue many many times, even if you are not really a strong opponent of immigration, why would you trust the elite ever again on it? There is the problem which faces the argument in your last paragraph. And of course they have to start with the major confession which kills their whole argument to voters stone dead – “we are not in a position to make the decisions anyway, we are not the organ grinder, it is mostly down to the EU, so we have to just carry out what we are told – whatever you say will not be listened to anyway. Get over it”…Can you hear the elite saying that, or even a pompous version of it?

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease #immigration concerns https://t.co/hnj3c1jQvx

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns https://t.co/jtthrmAt0o

Economic solutions unlikely to ease immigration concerns – importance of culture highlighted @cjnu1 @democraticaudit https://t.co/gP6wxxSajj

British perceptions of #immigration & #economy: article with @cjnu1 on our recent SSQ paper https://t.co/gP6wxxSajj https://t.co/xaNPD99TqZ

Craig Johnson and Sunil Roger argue economic solutions are unlikely to ease #immigration concerns in Britain https://t.co/7ObWwF4OuW

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns https://t.co/skWu6GAnyq

@democraticaudit article ‘#Economic solutions are unlikely to ease #immigration concerns’ https://t.co/79qlgNdRv0 #migration

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns https://t.co/d84coaPwJD

Economic solutions are unlikely to ease immigration concerns https://t.co/BRceebtfaG https://t.co/vgXoRI5mTM