Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of FOI requests

In July 2015 the government appointed a new independent commissionto look into how the law on freedom of information (FOI) is working. Having received 30,000 pieces of evidence, the commission has also managed to unite the Guardian and the Daily Mail against it while Labour has responded with its own alternative review. Here, Ben Worthy, Peter John, and Matia Vannoni explain how their field experiment provides evidence that FOI requests work, and that they are twice as likely to get a response than informal requests.

Credit: Heath Brandon CC BY-SA 2.0

In 2010 Tony Blair felt that passing the Freedom of Information Act 2000 was one of his biggest mistakes; in 2012 David Cameron claimed requests were ‘furring up the arteries’ of government. In 2015, FOI became controversial again when, after a Supreme Court ruling, the government appointed an independent commission to look into how the law is working. All the debate on the benefits and costs of FOI rest on one question, which is whether the law actually works as it should. Does FOI enable a user to ask a question and get a response? Do public bodies comply? Finding this out is trickier than it sounds. Simply measuring numbers of requests may not tell us much, as we need to measure it against something else. Some great attempts have been made in Brazil, Mexico and in an international 14 country study.

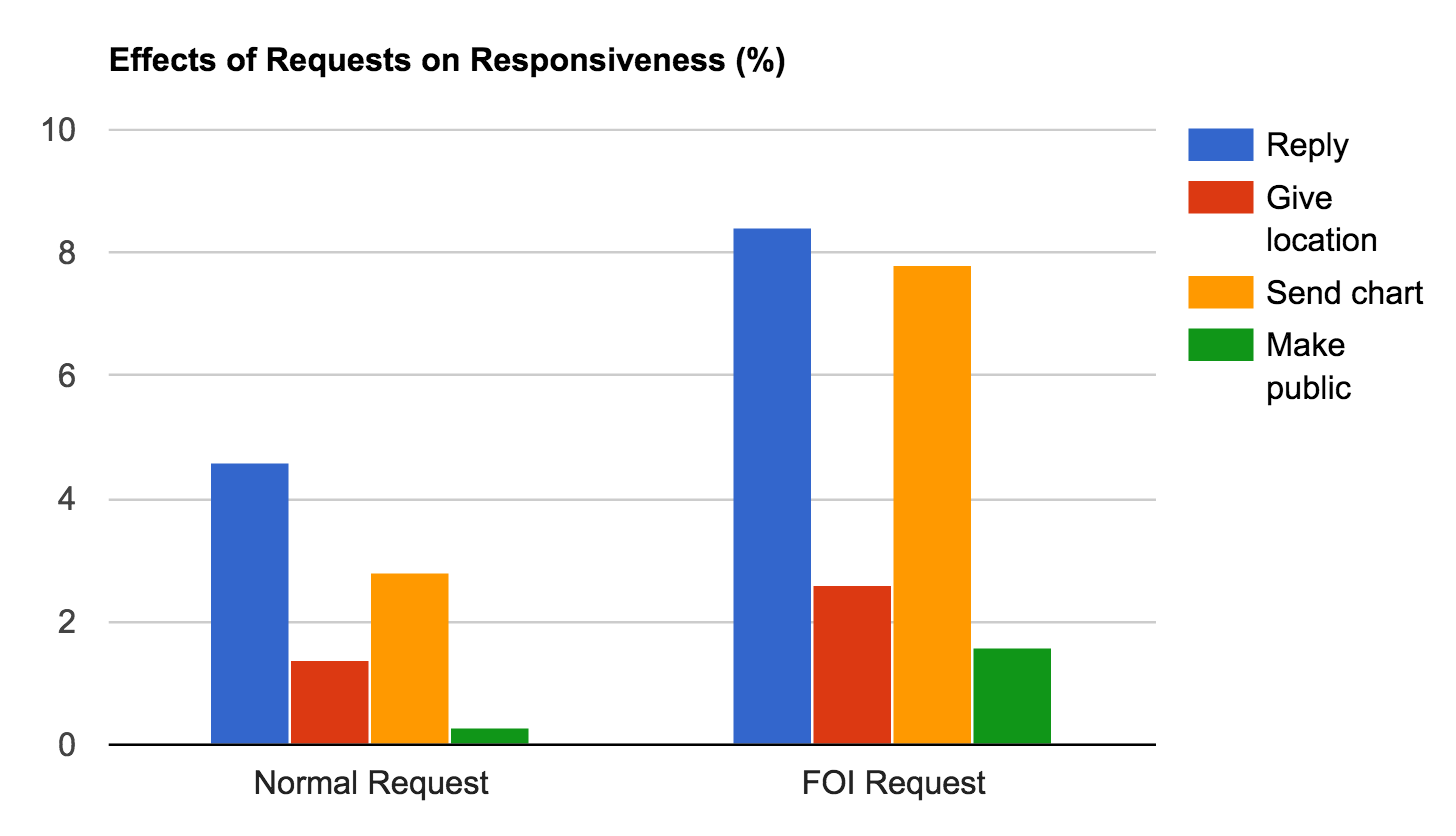

Building on these, we devised an experiment to compare whether a request under the law works better than a more informal route: that of simply asking. We sent out a series of similarly-worded FOI requests and informal asks – the former specifically mentioned the FOI Act. This way we hoped we could see if an FOI with the force of law worked better than just asking informally.

We decided to approach selected public bodies for a relatively innocuous and simple piece of information: an organisation chart (see some rather fancy ones here from central government). Our requests and asks not only sought information but also, as a bonus, asked ‘can you publish this request on your website?’. Our next question was who to ask. Parish councils were chosen as other parts of local government simply had so many requests ours would get lost.

Compared with other parts of the UK little is known about parish councils (see this briefing here). They are the lowest unit of local government in the UK, long-established systems of government at the town or village level that date back to the middle ages. They primarily cover rural areas and deal with local environmental, community and amenity issues, with additional discretionary powers over raising tax (via a small precept). There are some 9,500 councils and 95,000 councillors across England covering approximately 30 per cent of the population but almost all have populations of less than 10,000 people. They seem to get very few FOI requests, so our requests would not be lost in the ether.

We were worried that if we told public bodies what we were doing they may not behave normally so to ensure our research project did not bias responses we identified ourselves as belonging to a group calledMaking Parishes Better. We believe in the objectives of the project Making Parishes Better, and addresses and contact numbers were in evidence on the website.

So what was the result? First, the response rate was higher for FOI than just asking. To be exact an FOI was twice as likely to get a response as an informal approach. The bottleneck appeared to be over emails getting lost or going into junk at the earliest stage. Second, FOI triggered more compliance and our findings showed that FOI requests got stronger and not weaker the more was demanded. In comparative terms parishes were three times as responsive to our bonus demand that is not required by the FOI law. This is a sign that there are high levels of support for the principles of FOI once within the system.

Our experiment offers a first insight into whether FOI works. It doesn’t tell us everything about the how and why. However, amid all the debate and discussion of regrets and supposedly clogged arteries, it points to the fact that FOI does work in the way it should and is supported by officials. The results are positive, especially considering parish councils, the smallest public bodies in England, staffed by part-time staff and often with very little funding. An FOI is better than asking.

__

Note: graph figures might differ from the paper’s due to rounding; you can see the preliminary results here. The authors would like to thank all the parishes that helped provide the information and hope the research is of value to them, and that the information would have a democratic value to the community.

This post originally appeared on the LSE British Politics blog. It represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Ben Worthy is Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the author of “The Politics of Freedom of Information: How and Why Governments Pass Laws That Threaten Their Power” (forthcoming, MUP 2016).

Ben Worthy is Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the author of “The Politics of Freedom of Information: How and Why Governments Pass Laws That Threaten Their Power” (forthcoming, MUP 2016).

Peter John is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at UCL. His books include “Analysing Public Policy” (Routledge, 2nd edition, 2012) and “Making Policy Work” (Routledge 2011).

Peter John is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at UCL. His books include “Analysing Public Policy” (Routledge, 2nd edition, 2012) and “Making Policy Work” (Routledge 2011).

Matia Vannoni is a PhD candidate at the School of Public Policy, UCL. His research has been published in journals including British Politics and the Journal of European Public Policy.

Matia Vannoni is a PhD candidate at the School of Public Policy, UCL. His research has been published in journals including British Politics and the Journal of European Public Policy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of #FOI requests https://t.co/mI8HUhfOxs

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of FOI requests https://t.co/gDEee74REn

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of FOI requests https://t.co/naRtRTFTwb

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of Freedom of Information requests https://t.co/952d4iH8w5

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of FOI requests https://t.co/whiND6X39q

Freedom Of Information requests work better than simple questions with parish councils https://t.co/YdTXJAEEmC https://t.co/ixeRAZOX0y

The other thing this shows is the ridiculously low response rate from Parish Councils. Even with an explicit pointer to FoI, the average response rate was only 5%. Yes – only in 20 formal FoI requests was actually answered. This mirrors quite well my own experience in asking formal FoI questions about parish Councillor Register of Interests.

And of course the FoI Act says that all information requests should be treated as FoI requests even if you don’t explicitly state it – so Parish Councils still have a legal obligation to answer. In this case, only 1 in 50 requests were answered.

If anything says that the FoI needs to be strengthened, this is it.

Better than asking: An experiment on the effectiveness of FOI requests https://t.co/uxuXg3zwW6 https://t.co/ZEoL3S8TT7